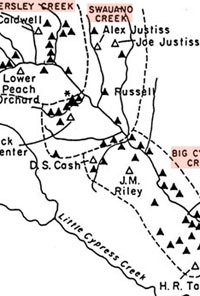

Distribution of Titus phase sites.

From Perttula, 1998.

Click images to enlarge

|

Titus phase settlements are sometimes found on upland

ridges protruding into the floodplains of the major and

minor streams. This example is near Benson's Crossing,

Big Cypress Creek, Titus County, Texas. TARL archives. |

Wooded bottomland along Cooper Creek, a tributary of the

South Sulphur River. This was near the western edge of

the area within which the Titus phase is found. The Blackland

Prairie to the west of the Cross Timbers formed the western

periphery of the Caddo Homeland. Photo by Bill Martin. |

Plan of the Ear Spool site, a Titus

phase hamlet in Titus County. Three circular houses

were uncovered on one side of a small plaza. On the

opposite side was a "special building" with

an extended entranceway and supports for interior benches.

There were several burials, one inside a house. Courtesy

PBS&J.

|

Looted Titus phase cemetery in Marion

County. Photo by Tim Perttula.

|

Turkey vulture effigy "tail-rider"

bowl, probably a trade piece from the Frankston phase

area, from looted Titus phase cemetery in Big Cypress

Creek drainage.

|

Titus phase pottery from cemetery

at the Russell site. The red Avery Engraved bowl in

the middle is probably a trade piece from the McCurtain

phase area in the Red River Valley to the north. TARL

archives.

|

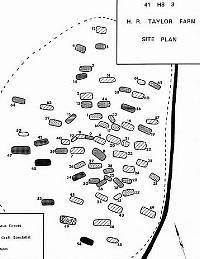

Plan of a Titus phase community cemetery (about A.D. 1600-1700)

at the Taylor Farms site near Lake O' the Pines within

the valley of Big Cypress Creek in northeast Texas. The

University of Texas excavated this site in 1931 and documented

64 graves. Note the consistent east-west grave orientation

and the fact that the graves do not intrude into one another. |

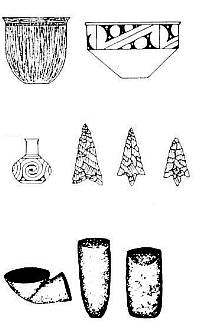

Large, thin chipped-stone knives

like these are found in Titus phase burials thought

to be those of high-status adult males. These examples

are from looted burials in the Big Cypress Creek drainage.

Several of these (if not all four) appear to be made

of Edwards chert from central Texas.

|

Celt (ground stone axe head) and

a pair of stone ear spools from Titus phase burial,

Lower Peach Orchard site, Camp County. TARL archives.

|

Typical Titus phase artifacts.

|

Taylor Engraved bottle with highly

unusual "spiked gaping mouth." Titus phase,

Taylor Farm site, Harrison County, Texas, height = 15.5

cm. TARL collections.

|

Wilder Engraved bottle, Titus phase,

Mattie Grandy site, Franklin County, Texas, height =

20.9 cm. TARL collections.

|

Keno Trailed bottle, Titus phase,

Taylor Farm site, Harrison County, Texas, height = 21

cm. TARL collections.

|

LaRue Neck Banded jar, Late Caddo,

ca. A.D. 1400-1650, J. M. Riley site, Upshur County, Texas,

height = 16.5 cm, diameter = 15.3 cm. TARL collections.

|

Ripley Engraved bowl with kaolin-filled

S-shaped scroll design. Shelby site, Camp County, Texas.

Courtesy Dee Ann Story.

|

Polished red bottle with negative

engraved scrolls. A very similar bottle is known from

the Hatchel site (41BW3) on the Red River, and this

vessel may have been traded from the Red River Caddo

to the Titus phase Caddo living the Shelby site. Courtesy

Dee Ann Story.

|

|

The archeological traces of Caddo groups who

lived between the Sabine and Sulphur rivers in the East Texas

Pineywoods between about A.D. 1430-1680 are known as the Titus

phase. Of the several hundred identified sites with Titus

phase occupations, the largest concentration occurs in the

Cypress Bayou (or Big Cypress Creek) Valley. Other Titus phase

sites are found throughout the valley of the Little Cypress

Creek, the southmiddle portions of the Sulphur River basin,

the middle and upper portions of the White Oak Creek drainage,

and the upper and middle reaches of the Sabine River drainage.

Closely related communities were present in the Toledo Bend

area farther to the south along the Sabine River in Louisiana

and Texas and probably represent a late movement of Titus

phase people.

Archeologist Pete Thurmond sees the Titus phase

has being made up of four contemporaneous subclusters: the

Three Basins, Tankersley Creek, Swauano Creek, and Big Cypress

Creek. In addition, Robert Turner has proposed early and late

periods within the Titus phase based on design motif variations

on Ripley Engraved carinated bowls and changes in vessel form.

Combining both ideas, there are apparent geographical clusters

within the Titus phase as well as noticeable changes through

time.

Thurman defined his subclusters based on differences

in the design motifs found on the most common type of decorated

Titus phase pottery, Ripley Engraved bowls, as well as differences

in other shared pottery types, and the distribution of different

arrow point styles across the area. He argues that the Titus

phase subclusters represent separate tribes or subtribes similar

to the named groups who made up the historically known Hasinai

and Cadohadacho alliances. The overall Titus phase seems to

represent the archeological remains of a series of tribes/groups

banded together in an alliance analogous to, and at least

partially contemporaneous, with that of the Hasinai to the

south and the Kadohadacho to the northeast.

In general, Late Caddo societies seem to have

had a three-tier social/political hierarchy. At the top were

civic-ritual centers that had platform (temple) mounds, burial

mounds, and presumably the residences of principal leaders

(caddis as well as the xinesi and lesser priests). The larger

examples of these are found along the major stream valleys,

such as the Red, Ouachita, and Little rivers, but smaller

centers were also present in smaller drainages such as along

Big Cypress Creek (Titus phase). Below the civic-ritual centers

(in size and presumably status) were small mound centers that

lacked burial mounds or large platform mounds. Instead they

had small mounds that capped burned and ritually dismantled

structures functionally equivalent to those found on the platform

(temple) mounds at the larger centers. At the bottom of the

social ladder were small but widely distributed rural communities

made up of many farmsteads and hamlets often spread out along

smaller streams and across productive upland areas.

For the Titus phase, Thurmond recognized three

types/sizes of settlements: limited use areas, small settlements,

and large settlements. The limited use areas are places that

were used only in certain seasons for short-term stays such

as camps for hunting, nut-gathering, and salt-making. In contrast,

the small and large settlements were occupied year-round.

Small settlements (between 0.2-1.8 hectares or 0.5-4.5 acres

in size) account for 73 percentage of the known Titus phase settlements

in the Cypress Creek basin, the limited use areas 23 percentage, and

the large settlements (those larger than 1.8 hectare or 4.5

acres) only 4 percentage of the sample.

One of the more intensively investigated large

Titus phase settlements is the Pilgrim's Pride site along

Big Cypress Creek at its confluence with Walkers Creek. Residential

areas at the site cover between 5-10 acres, with more than

100 pit features, several circular structures, midden deposits,

and more than 20 burials, along with an open plaza-like area.

Several of the burials appear to have been placed in and near

the floors of structures, but the Pilgrim's Pride site also

had a planned cemetery with at least 19 burials.

The small settlements appear to have been home

to one or several family compounds marked today by scattered

house middens often containing daub (fired clay) and trash-heap

(midden) mounds. Midden mounds up to one meter in height were

common on Titus phase settlements before they began to be

plowed in historic times. Excavations suggest that many activities

occurred outside the houses, resulting in trash-filled pits,

hearths, and posts in these areas, where ramadas and granaries

may also have been present, along with concentrations of artifacts

and debris. The limited evidence of structure rebuilding,

suggests that most Titus phase settlements were occupied only

about a generation. Small family cemeteries typically occurred

nearby.

Because of the intense avocational and professional

and focus on the cemeteries that occur on Titus phase settlements,

as well as significant looting of these sites since the early

20th century, little is known about the types of houses and

storage structures used by these groups. Based on the few

houses that have been excavated (some of which were in mounds

and probably are not ordinary domestic structures), houses

were probably circular in shape, with wattle and daub walls

(sometimes) and thatched roofs. They were between five and

eight meters in diameter and some, especially those capped

by mounds, have extended entranceways. Within the houses were

central hearths and center posts, possible interior benches

and racks for sleeping and storage, as well as storage and

trash pits. Residential structures had some midden accumulation

on their floors (i.e., house middens), which were not prepared

or clay-lined, but the vast majority of the daily trash and

refuse was deposited on the nearby trash midden mound.

When Pedro Vial visited the Nadaco Caddo "village"

near the Sabine River in 1788 (probably in the vicinity of

Longview and Marshall, Texas), he described it as having thirteen

to fifteen houses scattered over a distance of three leagues

(about eight miles). The houses or ranchos of the Nadaco were

evidently distributed mainly along tributaries of the Sabine

River. The distribution of Titus phase settlements suggests

that agricultural farmsteads and hamlets were scattered similarly

in prehistoric times, usually being found near springs or

along smaller streams, where good soil and fairly level ground

for farming was present.

The permanent settlements and larger cemeteries

of the Titus phase tend to be found near springs. In contrast,

Late Caddo mound centers typically do not occur in proximity

to a spring, but rather are on the floodplains of major rivers

and large creeks or they are situated on ridges that jut into

and overlook large floodplains.

Mound-building in the Late Caddo period in the

Pineywoods outside of the Red River valley was once thought

to have ceased between roughly A.D. 1400 and 1500, but dates

from several sites in Upshur and Camp counties suggest mound-building

may have continued in the Titus phase "heartland"

until about A.D. 1600 or later. Only a modest number of Late

Caddoan period mounds are known in the region, ranging from

one to four small mounds per site.

There are two types of cemeteries used by the

Titus phase groups: the small family cemetery, and the large

community cemetery. More than 130 Titus phase cemeteries have

been documented to date.

The small family cemeteries contain roughly

equal numbers of adult males and females and are located near

farmsteads or hamlets. Such cemeteries in the western margins

of the Titus phase area have about 10-20 individuals while

those in the Titus "heartland" along Big Cypress

bayou have 20-40 graves. There are few indications of differential

status or social rank in grave good associations and burial

treatment in family cemeteries. Typically, the graves are

laid out in rows with the individuals in extended positions

oriented roughly east-west. Children were typically buried

in subfloor pits within the houses themselves. Artifact associations

in family cemeteries seem to differ only by age and sex. Older

individuals are buried with more offerings than younger ones.

Men's graves often contain clusters of arrow points in patterns

suggesting quivers of arrows. Women's graves contain polishing

stones or more numerous pottery vessels. Items of exotic material

are quite rare in family cemeteries.

The large community cemeteries of the

Titus phase seem to have served several communities in the

vicinity. These cemeteries usually contain at least 60-70

individuals, but some are known that contained at least 150-300

individuals. Large community cemeteries show the existence

of different social classes within the Titus phase Caddo communities.

Known community cemeteries are not uniformly distributed among

the Titus phase groups, but are concentrated on Big Cypress

Bayou and several of its eastward-flowing tributaries (i.e.,

Walkers Creek, Dry Creek, Greasy Creek, Meddlin Creek, and

Arms Creek), the Titus phase "heartland," with a

few large cemeteries known on Little Cypress and White Oak

creeks. Presumably, the areas where these larger cemeteries

are found had the highest population densities and more complex

societies.

The larger community cemeteries are internally

organized by space and structurally divided by rank. Graves

rarely overlap and it looks like the cemeteries expanded over

time. Since the cemetery plan was consistently maintained,

they may reflect stable communities over several generations.

Four criteria have been used to identify social

status ranking in Titus phase cemeteries: the presence of

large shaft tombs, the number of individuals per grave, the

relative quantity of grave goods, and the presence of certain

types of presumed high-status artifacts. Large shaft tombs

and those with multiple interments are considered to be high-status

burials; all other Titus phase burials are single, individual

burials. Family cemeteries do not contain shaft tombs or multiple

interments. The high status burials also contain larger numbers

of grave offerings ( over 30 compared to an overall average

of about 15 per grave) than those of other burials. There

are also certain types of artifacts only found in high-status

burials. For example, in the Cypress and Upper Sabine basins,

large, thin chipped-stone knives are almost always found with

high status adult males.

There are 18 known Titus phase sites in the

Pineywoods that have burials of presumed high-status individuals,

such as J. E. Galt, Caldwell, Lower Peach Orchard, Tuck Carpenter,

H. R. Taylor, and others; these are along Big Cypress Bayou

and its tributaries, particularly in the Titus phase "heartland"

between the dam site at Lake Bob Sandlin and the Lake O' the

Pines dam, and western and southern tributaries such as Dry

Creek, Greasy Creek, and Arms Creek. Other cemeteries with

high rank burials occur in the Little Cypress Creek valley,

along a Sabine River tributary, and on White Oak Bayou. The

best-known and studied community cemeteries with high-status

burials are the Tuck Carpenter and H. R. Taylor sites.

At the Tuck Carpenter cemetery, high-status

burials dating between ca. A.D. 1350-1550 are at the center

of the 70+ interments in the cemetery, while the latest high-status

burials (estimated to date after ca. A.D. 1550 to the early

1600s) were placed near the outer edge of the cemetery. With

the exception of the two graves with multiple interments,

graves contained single individuals in extended position that

were placed in the cemetery in roughly aligned north-south

rows. The high-status burials contained on average 37 grave

offerings per burial (large numbers of ceramic vessels and

arrow points), compared to about 15 grave goods per burial

for the cemetery as a whole.

A similar pattern is seen in the graves in the

cemetery at the H. R. Taylor site. Mean values of ceramic

vessels (8.3 per individual), arrow points (5.09 per individual),

and total number of specimens (14.5 per individual) as grave

offerings at H. R. Taylor are not significantly different

from other Titus phase cemeteries, but the high-status burials

each contained between 27-55 grave offerings.

High-status individuals account for 8 and 9 percentage

of the burials at H. R. Taylor and Tuck Carpenter, respectively.

Overall, in the Titus phase mortuary populations, high-status

individuals account for less than 2 percentage of all known burials,

showing that the community cemeteries were associated with

the mound centers where the leading members of the Titus phase

societies presumably lived. In contrast, lower-status interments,

namely those lacking grave goods or containing only small

quantities (0 to 9.0 items at Tuck Carpenter and 0 to 6.7

items at H. R. Taylor), account for 19 percentage and 23 percentage of the burials

at the two sites, respectively. As judged by the grave goods,

lower-status individuals at both these community cemeteries

were usually adult females, juveniles, or children. Most of

the individuals at both cemeteries, 73 percentage at H.R. Taylor and

68 percentage at Tuck Carpenter, fall within the middle category of

neither high nor low status.

The majority of known Titus phase burials of

apparent high-status appear to date after ca. A.D. 1550-1600.

Those individuals buried prior to A.D. 1550 demonstrate considerable

intra-regional variability in the manner of burial treatment,

as well as in the types of grave offerings. For example, in

addition to the multiple interments at Tuck Carpenter, shaft

tombs are represented in a pre-A.D. 1550 cemetery at the Lower

Peach Orchard site. At the J. E. Galt site, the high-status

burial included such offerings as a large number of celt fragments

and other native stone implements, rather than caches of arrow

points. Galt bifaces were also recovered from the cemetery.

In general, community cemeteries are relatively

short-lived phenomena that were used intensively in the core

Titus phase area in the basin of Big Cypress Creek after about

A.D. 1550 to the early 1600s. It is probably no coincidence

that the period of the most intensive use of community cemeteries

seems to be roughly contemporaneously with the initial contact

between Titus phase Caddo populations and the Spanish De Soto/Moscoso

entrada of 1542-1543. The short-term use of these cemeteries

could, in part, reflect deaths due to conflicts with the Spanish

army as well as increased mortality from European diseases.

The timing in the intensification of the use of large community

cemeteries in the region also seems to occur at about the

same time that mound centers ceased to be used for community

ritual and religious functions by about the 1550s or slightly

later. Collectively, the changes occurring after 1550 reflect

rapidly changing societies on the eve of (or in the process

of) group consolidation and the eventual Caddo abandonment

of the Pineywoods of northeast Texas.

One of the most striking aspects of the Titus

phase archeological record is the diversity and distinctiveness

of the pottery found in settlements and cemeteries. The wide

variety of vessel shapes and decorations, as well as their

frequency in domestic contexts, demonstrates the importance

of pottery for cooking and serving food, as personal possessions,

and as social identifiers. Large quantities of both fine wares

and utility wares were manufactured in the Titus phase.

The fine wares were tempered with finely crushed

grog (pottery) and bone, and were well-polished; shell-tempered

vessels are quite rare, and when found, are typically trade

wares from the Red River Caddo. Titus fine ware was decorated

with engraved lines, with scrolls, scrolls and circles, pendant

triangles, and other curvilinear motifs. Another form of decoration

was the application of a red hematite (ochre) slip on both

interior and exterior surfaces, and the painting of engraved

lines with red hematite or white kaolin. The diversity of

vessel forms is impressive: carinated bowls, compound bowls,

bottles, cone-shaped bowls, ollas, jars with flaring rims,

square bowls, globular peaked jars, and chalices. Animal effigies

and rattle bowls were also made.

The utility vessels were tempered with grog

and grit (crushed stone such as sandstone and hematite), and

had a coarser paste along with a thicker body. Small to large

jars (over 30 centimeters or 12 inches in height with mouth

diameters greater than 25-30 cm) and plain conical bowls were

typical utility vessel shapes. The presence of carbon encrustations,

food residues, and sooting on many of the utility vessels

show clearly that these were cooking pots. The larger utility

vessels were probably mainly used for storage of food (wide/flaring

mouths) and liquids (narrow/constricted mouths).

Utility vessels were decorated and textured

with neck-banding, brushing, applique, incising, punctating,

and various combinations thereof. Small handles or lugs were

added to some utility vessels. Utility vessels probably comprised

between 50 to 70 percentage of the ceramic assemblages in Titus phase

settlements. Far fewer utility vessels, proportionally, are

found in Titus phase cemeteries.

Titus phase groups also made ceramic earspools,

as well as tubular and elbow pipes of clay. Earspools were

also made from siltstone and sandstone, as well as wood. One

set of earspools from the Tuck Carpenter site had been covered

with sheet copper. The elbow pipes are commonly decorated

with engraved lines that have been painted (filled) with red

hematite or white kaolin clay.

Compared to earlier periods, stone tools and

tool-making debris are generally uncommon at Late Caddo period

sites in the Pineywoods. We suspect this is because many tools

were made out of wood, cane, bone, and shell, few examples

of which are preserved in the archeological record. The relatively

few stone tools types present also indicate the increased

importance of other materials at the expense of stone. Common

stone tools include triangular and corner-notched arrow points,

flake tools (drills, scrapers, and retouched pieces), along

with an array of groundstone implements. These include celts,

metates and manos, battered and polished cobbles and pebbles,

hematite and limonite pigment stones, and abrading slabs.

Although bone is usually poorly preserved in

Titus phase sites, many different kinds of bone tools have

been found in favorable contexts. Among these are deer-mandible

cutting tools, deer beamers (hide-working tools), deer ulna

punches, antler-tine flaking tools, and deer and bird bone

pins. Turtle carapace rattles have also been found. Heavy

clam shell digging tools ("hoes") are sometimes

present.

Unfortunately, few studies have been done of

the diet of Titus phase groups based on charred plant and

animal remains, which are sometimes reasonably well preserved

in middens, hearths, and pit features. Charred plant remains

from trash midden deposits suggests that corn (Zea mays L.)

was the main dietary staple, but that beans (Phaseolus

vulgaris) were also an important food source. Nuts and

seeds were still gathered, but of lesser importance in the

Titus phase than they were between ca. A.D. 900-1400. In fact,

evidence from the Titus phase in the Pineywoods, as well as

elsewhere in the Caddo area, suggests that the Late Caddo

economy was based primarily on maize (corn).

Animal bones identified in Titus phase trash

middens include deer, turkey, cottontail rabbit, jackrabbit,

squirrel, and beaver. Turtle and fish were also present, but

were relatively uncommon compared to mammals and birds. Deer

and turkey appear to have been the main prey species.

Although many of the details are not yet understood,

grave goods and other exotic artifacts (such as marine whelk/conch

shell and certain stones) suggest that trade among "town

and country" Caddo communities and among Caddo groups

in different areas was flourishing at the time of initial

European contact in the sixteenth century. Titus phase people

were also part of long-distance trade and information networks

linking Caddo groups with farming peoples living in the Southwest,

Southern Plains, and lower Mississippi Valley.

The most common ceramic imports found in Titus

phase sites are those from the Red River Caddo groups. They

include such fine wares as Belcher Ridged, Belcher Engraved,

Glassell Engraved, and Hodges Engraved from the Belcher phase

to the east, and shell-tempered Avery Engraved and Simms Engraved

pottery types of the McCurtain and Texarkana phases to the

north some 100 kilometers (62 miles). Red River gravel chert

(flint) and chalcedony was found to make up about 20 percentage of the

stone tools and debris in the Three Basin subcluster of the

Titus phase. Hatton tuff and siliceous shales from the Ouachita

Mountains were used to make celts. Edwards chert from central

Texas is also found in Titus phase sites, showing the existence

of trade and exchange with non-Caddoan hunting and gathering

peoples living more than 150 kilometers (93 miles) to the

west and southwest of the Pineywoods Caddo.

New assessments of the route of the de Soto-Moscoso

1542-1543 entrada through East Texas suggest that the Spanish

encountered the Titus phase peoples described by the chroniclers

as the Lacane province. By 100-150 years later, the Titus

area had been virtually abandoned. The demise of the Titus

phase people is thought to be mainly due to the introduction

and, more importantly, the continued exposure of Caddo groups

to European epidemic diseases. It is likely that some Titus

phase peoples moved to live with either the Red River Kadohadacho,

or among the Hasinai Caddo south of the Sabine River.

Archeologists believe that Titus phase Caddo

sites in the Pineywoods hold great promise in helping to document

the nature of social, political, demographic, and economic

changes in the region during a most eventful era in Caddo

history. In part this is because improved dating now makes

it possible to use subtle pottery differences to pin down

the date of some sites and events (such as graves) to perhaps

within a 20- to 30-year period. As other studies of Caddo

archeology make clear, there have been substantial changes

in Caddo societies from ca. A.D. 800 to European contact.

One of the most important changes is the development and elaboration

of complicated forms of social and political organization

after ca. A.D. 1400 in many regions of the Caddo Homeland.

|

Titus phases subclusters as defined

by Pete Thurmond. From Perttula, 1998.

|

The bottomlands along Big Cypress Creek and its many tributaries

were rich sources of wild plant foods, wood, and game

for Titus phase peoples. Titus County, Texas. TARL Archives. |

Distribution of known Titus phase

mound centers; most, as can be seen, occur along Big

Cypress Creek. Adapted from Perttula, 1998.

|

Archeologists at work at the Benson's

Crossing site, a Middle Caddo period site near Big Cypress

Creek that probably represents the direct ancestors

of Titus phase people. The two-tone soil colors in the

excavation walls represent a dark midden deposit overlain

by a lighter colored plow-disturbed zone. TARL archives.

|

The distribution of large Titus phase

cemeteries is similar to that of Titus phase mound centers;

the two are obviously related. Adapted from Perttula,

1998.

|

Turtle effigy bottle from looted

Titus phase cemetery in Big Cypress Creek drainage.

|

A.T. Jackson holds two large, thin

chipped-stone knives found in a Titus phase cemetery

at the J. E. Galt farm in Franklin County during excavations

by the University of Texas in 1931. These "Galt

bifaces" could be more accurately described as

ceremonial knives or blades and, although no bones were

found, the knives were almost certainly offerings in

a high-status grave. TARL archives.

|

Plan of Titus phase community cemetery

(A.D. 1350-1600) at the Tuck Carpenter site located

on a tributary of Big Cypress Creek in Camp County,

Texas. Avocational archeologists and collectors excavated

this cemetery in the 1960s; 44 of the estimated 70+

graves were documented.

|

Grooved and decorated mace head,

probably from a high-status burial. Shelby site, Camp

County, Texas. Courtesy Dee Ann Story.

|

Engraved bottle with engraved bird

motif, Titus phase burial, Lower Peach Orchard site,

Camp County, Texas. TARL archives.

|

Ripley Engraved bowl, Titus phase,

Mattie Grandy site, Franklin County, Texas, height =

9 cm, TARL collections.

|

Hodges Engraved bottle with unusual

oblong form and pairs of nodes at both ends. Titus phase,

Taylor Farm site, Harrison County, Texas, height = 13.8

cm. TARL collections.

|

Karnack Brushed jar, Titus phase,

Taylor Farm site, Harrison County, Texas, height = 27.5

cm. TARL collections. Click on image for enlarged view.

|

Cass Appliqué jar, Titus phase,

Morris County, Texas, height = 17.6 cm. TARL Collections.

Click on image for enlarged view.

|

Harleton Appliquéd Jar, Titus

phase, Taylor Farm Site, Harrison County, Texas, height

= 10 cm, TARL collections.

|

Compound engraved bowl with unusual

(kaolin-filled) scroll motif. Shelby site, Camp County,

Texas. Courtesy Dee Ann Story.

|

Four-sided square bowl with unique

scroll motif and a protruding node or appendage, a rare

form of decoration on Titus phase vessels. Shelby site,

Camp County, Texas. Courtesy Dee Ann Story.

|

Unique bottle with trailed design.

Shelby site, Camp County, Texas. Courtesy Dee Ann Story.

|

|