This Haley Complicated-Incised jar

excavated by in 1911 by C.B. Moore dates to the Middle

Caddo period and is a good example of the exuberant

experimentation in pottery making that is characteristic

of the period. Haley Place, Miller County, Arkansas.

From Moore's 1912 report, Some Aboriginal Sites on Red

River.

|

Students and visiting archeologist

discuss findings and look at engraved bowl uncovered

at the Reavely House Mound at the Washington Square

site in Nacogdoches, Texas. Photo courtesy Dee Ann Story.

|

Ornate Haley Engraved bottle from

Middle Caddo Haley site, Miller County, Arkansas. Although

the decoration is exquisitely detailed, the paste and

firing of this pottery type is often inferior. Courtesy

Pictures of Record, Inc.

|

Untyped effigy bowl with engraved

designs. Effigy bowls may be another example of a Middle

Caddo introduction, probably from southwestern Arkansas.

Haley site, Miller County, Arkansas. Courtesy Pictures

of Record, Inc.

|

Haley Engraved bottle, Middle Caddo,

Haley site. From Moore, 1912.

|

|

The Middle Caddo period (A.D. 1200-1400)

was a time of changing settlement patterns, economic changes,

and exuberant experimentation with engraved and utilitarian pottery styles.

In fact, archeologists sometimes have difficulty recognizing

Middle Caddo sites as such because there are few well-defined

pottery styles. Compared to the Early Caddo pottery, which

looks very similar from place to place, the fine wares made

by Middle Caddo potters express far greater individuality

and creativity.

This upsurge in ceramic creativity during the

13th and 14th centuries coincides with the expansion of Caddo

settlements in many places across the homeland. A shift seems

to have taken place from a predominance of larger mound centers

like the Crenshaw and Davis sites to smaller communities including

small villages and hamlets as well as agricultural farmsteads.

This shift may be mainly a reflection of an economic shift

from a more diverse economy toward increasing reliance on

corn agriculture. Corn farming requires lots of space and

the growing crop must be closely watched, weeded, and, as

it matures, guarded to keep birds and mammals (especially

raccoons) from ravaging the corn. Many Caddo farmers moved to the

country, so to speak.

In recent decades archeologists have investigated

various large and small sites dating primarily to the Middle

Caddo period. They have found everything from small seasonal

campsites or single-family farmsteads that seem to lack substantial

houses and refuse middens to ritual (mound) centers that continue

many of the patterns seen at the Davis site (which continued

well into the Middle Caddo period). The larger sites were

important civic-ceremonial centers containing multiple mounds

and associated villages. The multiple mound centers are rather

evenly spaced along the Red River, the Sabine River, and Big

Cypress Bayou, and those that are contemporaneous may represent

an integrated regional network of interaction and redistribution.

For example, the Jamestown (eight mounds and village), Boxed

Springs (four mounds, village, and large cemetery), and Hudnall-Pirtle

(eight mounds and 60-acre village) sites appear to represent

the apexes (central places) of three Early and Middle Caddo

networks in the Sabine River basin.

Among the premier mound centers in the Neches-Angelina

river basin, the Washington Square site in the

middle of what is today Nacogdoches, Texas, dates mainly to

the Middle Caddo period. The site once consisted of at least

three mounds separated by a long plaza area and with an associated

village. Most of the site has been destroyed as Nacogdoches

has grown. Two mound remnants have been partially excavated

by Jim Corbin and his students at Stephen F. Austin State University

and the 1985 field school of the Texas Archeological Society.

Extensive excavations documented a circular structure under

Mound 1/2, an assortment of pits and postholes in non-mound

contexts, and several large burial pits in a mortuary mound

(the Reavely-House Mound). Although little evidence of the

village apparently survives, large sherd-filled pits (representing

many vessels) were encountered in an area between the two

mounds. These are thought to be deposits from public feasting

activities led by the Caddo elite that used the Washington

Square site as a ceremonial center in the 13th and 14th centuries.

The Haley site is another ceremonial

center dating to the Middle Caddo period and one of the most

famous of all Caddo sites. It is located on a levee of the

Red River in southwestern Arkansas about 20 miles north of

the Louisiana state line. The Haley site had two prominent

mounds and probably once had other smaller mounds. C.B. Moore

excavated most of one mounds in 1912, finding nine shaft tombs

now known to date to the Middle Caddo period. He tested the

other mound and, finding no burials, concluded (probably correctly)

it was a "temple mound." Since the 1960s, amateur

archeologists and pothunters have found two sizable cemeteries

at the site and have dug up over 100 burials.

Although some archeologists have suggested that

Haley was strictly a "ceremonial and burial center,"

we suspect that associated village areas were close by. The

Haley site is best known for its unusually ornate pottery,

which exemplifies Middle Caddo pottery creativity. Tellingly,

many of the pottery styles found at Haley are known only from

a short stretch of the Red River Valley extending southward

into northernmost Louisiana. A few obvious trade pieces do

show up elsewhere, but the limited distribution area must

demark the territory of the local group (polity).

|

Large Haley Engraved bowl with handles

and protruding nodes, decorative flourishes that Caddo

potters began making in the Middle Caddo period. From

Moore, 1912.

Click images to enlarge

|

Trade vessel from the central Mississippi

Valley, probably Nashville Negative Painted, found by

C.B. Moore in a grave at the Middle Caddo Haley site.

From Moore, 1912.

|

This engraved bowl is one of the

grave offerings of a Middle Caddo period burial that

was narrowly missed by a gas pipe in the front yard

of the Reavely House. Photo by Dee Ann Story.

|

Handy Engraved bowl. The addition

of handles is another innovation of Middle Caddo potters.

Haley site, Miller County, Arkansas. Museum of the Red

River, Idabel, Oklahoma Courtesy Pictures of Record,

Inc.

|

Handy Engraved jar, Middle Caddo,

Haley site. From Moore, 1912.

|

|

|

House and building outlines exposed

at the Oak Hill Village site. Courtesy PBS&J.

|

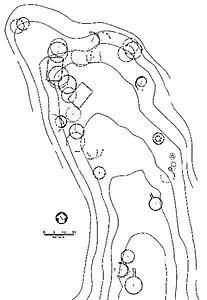

Plan of the Oak Hill Village. More

is now known about this site in Rusk County, Texas than

perhaps any other site dating to the Middle Caddo period.

Courtesy PBS&J.

|

|

These

pottery sherds from Oak Hill Village show some of the

variation in pottery decoration present at the site. Courtesy PBS&J. |

Overlapping circular house outlines.

Stakes of two colors mark the outline of the two houses.

Courtesy PBS&J.

|

The barely visible outline of Structure

2, a special building with an extended entranceway,

as it was first found. Late Village at Oak Hill site.

Courtesy PBS&J.

|

Outline of a "special building"

with extended entrance shortly after it was recognized

at the Oak Hill Village. This structure dates to the

Late Village. Courtesy PBS&J.

|

Close up of the wall trench on one

side of the entranceway to Structure 2. The narrow entranceway

had picket walls and two large posts at the entrance

to which wooden statues or emblems marking the building

as sacred space may have been attached. Late Village,

Oak Hill site. Courtesy PBS&J.

|

Two overlapping house outlines that

may represent a dilapidated house from which the timbers

were salvaged to build a second house on almost the

same spot. Middle Village, Oak Hill. Courtesy PBS&J.

|

Examples of the variety in size and

number of rows among the charred corn cobs from the

Oak Hill Village. Courtesy PBS&J.

|

Variation on a Middle Caddo engraved

bowl #1. Oak Hill Village. Courtesy PBS&J.

|

Variation on a Middle Caddo engraved

bowl #2. Oak Hill Village. Courtesy PBS&J.

|

Variation on a Middle Caddo engraved

bowl #3. Oak Hill Village. Courtesy PBS&J.

|

|

Some 100 miles to the southwest from Haley,

a fascinating Middle Caddo village was discovered during archeological

investigations in advance of a large lignite (coal) surface

mine. The Oak Hill Village site in Rusk County, Texas,

occupied a small ridge overlooking Mill Creek, a tributary

of the Sabine River. More is now known about this Oak Hill

Village site in Rusk County, Texas than perhaps any other

site dating to the period. On behalf of TXU Mining Company

LP, archeologists from the private consulting firm PBS&J

used heavy machinery and hand excavation to open up broad

areas, and thus were able to expose the "footprint"

of virtually an entire small village. Postholes and pits dug

through the sandy soil into the underlying clay were visible

once large areas of the site were scraped off with machines

and then cleaned by hand. The ridge upon which the village

was built had been plowed and contoured by modern farming,

thus disturbing the upper deposits of the site.

Oak Hill Village had at least 42 circular and

rectangular structures representing at least three successive

villages. The structures that were part of the last and largest

village were arranged over a 3.5-acre area in a circular pattern

around a central plaza area. Sorting out which of the structures

were contemporaneous was very difficult because some of the

structures had been rebuilt over and over and some overlapped

earlier structures, particularly at the northwestern end of

the ridge and plaza. Working out how the village changed during

its 300-year span was also hard because most of the structures

were only recognized after the heavy machines had scraped

away what would have been the floor level (thus, removing

any evidence of the actual house floors and artifacts that

had survived modern plowing). Nonetheless, analysts were able

to work out the basic sequence of the village phases, called

here the early, middle, and late villages.

The Early Village at Oak Hill began as early

as A.D. 1150 (or perhaps a few decades later). It consisted

of four large rectangular structures, each measuring about

7 x 11 meters (23 x 36 feet). These are thought to be houses

that would have been suitable for 10-20 people. A total of

40-70 people probably lived at the site during this phase.

Rectangular houses are not common in the region, but are known

at other Middle Caddo sites, including the Ferguson site in Arkansas,

the Belcher site in Louisiana, and the Hines site in Wood

County, Texas. The early houses at Oak Hill were not arranged

around a plaza.

By A.D. 1250 the Middle Village had been reorganized

and the house style had changed from rectangular to circular

buildings like those typical of most Caddo sites in northeast

Texas. The middle village phase was the most intensive of

the three and lasted a full 100 years. Most of the superimposed

building patterns (most of them surely houses) date to this

phase. The exact number of houses in use at any one time is

unknown because of the overlapping outlines. The structures

making up the middle village at Oak Hill were arranged around

an open plaza covering at least 15 x 25 meters (about 50 x 80

feet). The total village population is estimated at between

75 and 100 people.

One of the clusters of three overlapping structural

patterns at the north end of the Middle Village was apparently

covered by a low mound, upon which a new building may have

been placed (the evidence was destroyed by plowing and machine

scraping). This mound probably covered a special building

of some sort, perhaps the house of the village headman or

a small temple.

During the Late Village phase, dating from about

A.D. 1350 to as late as 1450, the village expanded to the

south and new types of structures were built along with more

of the circular houses. Total village population is estimated

to have reached an all-time high of at least 100, perhaps

a bit more. Two of the new structures at the south end have

long extended entranceways pointing to the north (and the

main village area). These are clearly "special buildings"

although it is not known whether they were temples or the

houses of the village headman or priest. Also new during the

Late Village is the addition of interior partitions to several

buildings and the construction of four small circular structures

thought to be granaries.

Although the Oak Hill Village deserves a full TBH site exhibit, a few tantalizing details are presented below and in the accompanying photographs, based on the work of the archeologists who analyzed and reported the Oak Hill Village,

Robert Rogers and Timothy K. Perttula, and their colleagues.

The main construction timber used throughout

the life of the Oak Hill villages was oak. There is no evidence

that any of the buildings were burned, suggesting that they

decayed naturally after use life of no more than 15 years.

One technique used to prolong the life of the upright timbers

was to char the ends of the posts that were set into the ground.

Some of the overlapping and intersecting house patterns suggest

that some of the houses were rebuilt using borrowed timbers

(perhaps those that had snapped off at the ground level).

Many charred corn cobs were found in several

pits within houses that were either cooking fires or what archeologists

call "smudge pits," fires intended to produce lots

of smoke either for smoking meat or keeping mosquitoes at

bay. The fragmentary cobs were studied by plant experts (paleobotanists)

who suspect the diverse sample represents as many as three

or four different varieties of corn. Eight, 10, 12, and 14-row forms were found, although the number of rows

is not clearly linked to variety (ears with different numbers

of rows occur within a single variety). While it was not possible

to identify these as known varieties, it does seem likely

that the Oak Hill villagers were growing several different

types of corn. This fits with early historic accounts that

describe the Hasinai groups growing an early maturing flint

corn and a later maturing flour corn. You can see the advantage

of having varieties that could be grown at different times

of the year and those that would tolerate drought better.

The 300-year span of the successive Oak Hill

villages illustrates nicely the increasing importance of corn.

Corn was found in 32% of the Early Village soil samples from

hearths and pits, 50% of the Middle Village samples, and 97%

of the Late Village samples. The Late Village granaries reinforce

these data. The village economy, though, depended on a mix

of crops, wild plants, and wild animals throughout the site's

history. Hickory nuts are present in almost every sample.

Other nuts include acorns and walnuts. Fruits that were eaten

include persimmons, dewberries, and grapes. The finding of

charred maygrass and goosefoot/pigweed indicates that these

starchy seeded weeds were probably grown (or encouraged) as

well. Deer was the hunter's favorite target and the main protein

source. Other hunted or trapped animals include rabbits, buffalo

(a single animal), and squirrel. Fish, birds, and reptiles

round out the list and that is only what was preserved. Dozens

of other plant and animal species would have been part of

the diet.

|

Outline of a large rectangular house

dating to the Early Village at Oak Hill. Such houses

could have accommodated 10-20 people. Courtesy PBS&J.

|

Top of pit filled with charred corn

cobs. Archeologists usually call such features smudge

pits,out of the belief that these were fires intended

to produce lots of smoke either for smoking meat or

keeping mosquitoes at bay. Alternatively, they may be

cooking pits that used corn cobs for fuel. Courtesy

PBS&J.

|

Detail of the overlapping and superimposed

house outlines at the northwest end of the ridge at

the Oak Hill Village dating to the Early (rectangular)

and Middle (circular) villages. Courtesy PBS&J.

|

Large pit perhaps used for storage

and later filled with trash. Oak Hill Village. Courtesy PBS&J.

|

Remnants of the charred outer rind

of this oak post survived for over 600 years. The charring

was done to keep the post from rotting. Oak Hill Village.

Courtesy PBS&J.

|

Eight, ten, twelve, and fourteen-row

corn cobs were found at Oak Hill Village. Although the

number of rows is not clearly linked to variety, plant

experts (paleobotanists) suspect the diverse sample

represents as many as three or four different varieties

of corn. Courtesy PBS&J.

|

Large sherd disk of unknown function

and engraved cylindrical jar from Oak Hill Village.

Courtesy PBS&J.

|

Perdiz arrow points from Oak Hill

Village. Courtesy Tim Perttula.

|

|

|

The old oak tree clinging to life at 516

North Mound Street in Nacogdoches, Texas guards what is left

of a burial mound dating to the Middle Caddo period, about

600-800 years ago. Long before the town was built, there was

a sizable Caddo community here. Ritual life centered around

three mounds forming a triangular plaza area. Photo by Dee

The old oak tree clinging to life at 516

North Mound Street in Nacogdoches, Texas guards what is left

of a burial mound dating to the Middle Caddo period, about

600-800 years ago. Long before the town was built, there was

a sizable Caddo community here. Ritual life centered around

three mounds forming a triangular plaza area. Photo by Dee