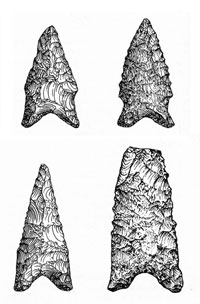

Dalton points from northeast Texas and

Oklahoma. From Johnson, 1989, courtesy Texas Historical Commission.

Click images to enlarge

|

Distribution of Dalton points. From Johnson,

1989, courtesy Texas Historical Commission.

|

Late Archaic (or early Woodland) dart points

and stone tools from the Coral Snake site on the Louisiana

side of the Sabine River in what is now Toledo Bend Reservoir.

All of these artifacts made from local materials, mostly fossilized

wood.

|

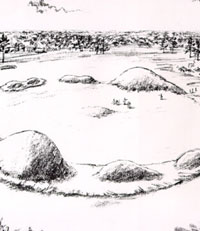

Early drawing of Poverty Point site in

northeast Louisiana. The Poverty Point earthworks included

a huge bird-shaped mound more than 70 feet (21 m) high and

710 feet (216 m) in length and a unique C-shaped array of

raised berms arranged into six concentric and nested rings

that are nearly three-quarters of a mile across (3,950 feet

or 1.2 km) at the widest point.

|

Petrified wood is one of the few materials

suitable for making chipped stone tools that is found in the

southwestern part of the Caddo Homeland (i.e., northeast Texas).

It was heavily used by Late Archaic times even though the

resulting dart points and tools were rather crude by comparison

to those made of flint (chert). These examples are from Cherokee

County. TARL archives.

|

Grooved stones such as these from the George

C. Davis site were part of the tool-making kit of Late Archaic

(and later) peoples in northeast Texas. The material is Catahoula

sandstone, which outcrops in the area. TARL archives.

|

Early to Late Archaic artifacts from the

Wolfshead site in San Augustine County, Texas near the Sabine

River in what is now Toledo Bend Reservoir. TARL archives.

|

Excavations in progress at the Hurricane

Hill site overlooking the South Sulphur River in Hopkins County,

Texas. This site contained Late Archaic, Woodland, and Early

to Middle Caddo components, although these were often difficult

to separate. Courtesy Tim Perttula.

|

|

The earliest peoples who lived in the area

that would become the Caddo Homeland were highly mobile hunters

and gatherers during the early Paleoindian era at the end

of the last ice age (Pleistocene), some 12,000-13,500 years ago

(10,000-11,500 B.C.). (A growing body of evidence suggests that people arrived in

North America thousands of years earlier, but the earliest evidence is

debated.) Early Paleoindian points including the Clovis and Folsom

styles have been found in the area as have distinctive lanceolate

spear and dart points dating to later Paleoindian cultures.

By around 8,000 B.C. artifacts of the Dalton and San

Patrice cultures are particularly common in the Southeast, suggesting

that populations are growing and that different cultures were developing.

Within the Caddo Homeland, evidence of Dalton culture is found mainly

to the north, while that of San Patrice is mainly to the south.

Beyond the region, Dalton points are concentrated in the Mississippi

Valley and are especially numerous in northeast Arkansas. These

contrasting patterns may reflect an early split between ethnic/linguistic

groups. We do not know how this inferred split relates to later peoples.

Dalton and San Patrice are considered by many archeologists

to be among the first of many Archaic cultures (or the latest Paleoindian groups) in the Southeastern

United States around 10,000 years ago, named for the distinctive dart points made by their

hunters. The entire Archaic period spans 7,500 years between

roughly 8,000 B.C. and 500 B.C. The Archaic concept was originally

proposed as a developmental stage during which mobile hunting cultures

gradually became more settled and more reliant on wild plants, small

game, and aquatic resources. In the broad sense, this view remains

accurate, but we now realize that Archaic cultures were quite varied

and responsible for many of the cultural developments once thought

to date to the succeeding Woodland era. For example, permanent or

semi-permanent village settlements, pottery, horticulture (gardening),

artificial earthen mounds, and extensive, long-distant trade of

exotic materials all appeared during Archaic times in various places

in the Southeast.

While most of the seemingly more advanced Archaic cultures

are known from areas hundreds of miles to the east and northeast

of the Caddo area, some very important developments took place in

the lower Mississippi Valley immediately to the east and southeast.

For instance, in what is today northeastern Louisiana, Archaic

peoples began building large earthen mounds as early as 4,000 B.C.

These were not burial mounds, but apparently served as platforms

upon which people lived. At Watson Brake near Monroe, Louisiana,

11 mounds 3 to 25 feet (1-8 meters) tall are connected by ridges

to form an oval enclosure over 850 feet (261 meters) across. The

Archaic mounds of Louisiana are all located adjacent to now-abandoned

river channels and were built by hunting and gathering peoples who

exploited the local swampy environments rich in aquatic life including

fish, fowl, and beast.

In the same region around 1700 B.C., massive

earthworks were built at the site of Poverty Point by peoples

who depended on aquatic and riverine resources. The Poverty Point

earthworks included a huge bird-shaped mound more than 70 feet (21

m) high and 710 feet (216 m) in length and a unique C-shaped array

of raised berms arranged into six concentric and nested rings that

are nearly three-quarters of a mile across (3,950 feet or 1.2 km)

at the widest point. Poverty Point is thought by many experts to

have been the center of a precocious society with far-flung trade

connections as indicated by the finding of many artifacts made of

exotic or non-local stone (some coming from sources hundreds of

miles away). These exotic items may have been sent to Poverty Point

in exchange for shell beads and ornaments, produced at Poverty Point

and at linked sites on the Gulf coast. For reasons yet unclear Poverty

Point culture had declined by 1000 B.C. and left no obvious successor.

As far as we now know, the later Archaic peoples living

in the Caddo Homeland did not build earthen mounds or form societies

comparable to the one responsible for Poverty Point. Late Archaic

groups in the region did participate at least indirectly in the

Poverty Point trade network. This is known because a variety of

artifacts have been found at Poverty Point that are made of materials

such as novaculite and quartz from the Ouachita Mountains. But Late

Archaic groups in the Caddo Homeland area seem to have been relatively

small societies who were not closely connected to the main areas

of the Eastern Woodlands where precocious developments were taking

place.

One such development was the beginning of plant domestication

and horticulture (gardening). In the past few decades archeologists

and ethnobotanists (specialists in how ancient peoples used plants)

have demonstrated that at least four plants were domesticated in

the Eastern Woodlands by 4,000 to 5,000 years ago (2000-3000 B.C.).

Through selective manipulation squash, sunflower, marsh elder, and

chenopodium (goosefoot) were all transformed from wild plants to

crop plants with larger seeds and other desirable characteristics.

The best evidence comes from only a few caves and open sites in

the American Midwest that have extraordinary preservation conditions.

The nearest one to the main Caddo Homeland is the Phillips Spring

site in the Ozark Plateau of southern Missouri, less than 300 miles

to the north of the Red River. Domesticated squash and bottle gourd

seeds found at Phillips Spring have been radiocarbon dated to at

least 5,000 years ago.

The discovery that these starchy and oily seed plants

were being cultivated in Middle and Late Archaic times has shattered

the traditional notion that the Archaic cultures of the Eastern

U.S. were purely hunters and gatherers. Clearly, Archaic peoples

were experimenting with plant cultivation and probably all sorts

of other manipulations of the natural environment such as selective

clearing, spreading desirable plants to new areas, and so on. Archeologists

are now reevaluating existing ideas about Archaic life.

Were the Late Archaic ancestors of the Caddo also

experimenting with gardening and growing starchy and oily seed plants?

We do not know. The view here is that it is very likely that some

Late Archaic groups in the Caddo Homeland area began experimenting

with planting seeds obtained through trade and exchange from peoples

to the north and northeast. But so far we do not have any "smoking

gun" evidence—preserved domesticated seeds. This is at

least partly due to prevailing preservation conditions and the lack

of concerted effort to recover the needed evidence from Late Archaic sites. This is a prime

research issue in need of more work.

What do we know about Late Archaic peoples in the

Caddo Homeland? The Late Archaic period between roughly 3000-500

B.C. in the Caddo Homeland remains rather poorly known. Isolated

and well-preserved Late Archaic site components (discrete deposits

from a single period or use episode) are uncommon and not many have

been studied. Nonetheless, Late Archaic-style dart points with expanding

and contracting stems including, among others, the Yarborough, Ellis,

and Edgewood types, are widely distributed throughout the area and,

at many sites, are more numerous than earlier styles. In much of

the region, Archaic lifeways seem to have persisted longer than

elsewhere in the Eastern Woodlands.

Compared to earlier periods, the Late Archaic seems

to have been a time of higher populations and of more intensive

use of the landscape—sites are found on all landforms from

major river terraces to upland ridges and everything in between.

At some sites, particularly in valleys on the north side of the

Ouachita Mountains and in the Great Bend area of Red River, refuse

middens (essentially, kitchen trash dumps) begin to accumulate in

Late Archaic times. The best known is the Wister phase of the Wister

Valley in far eastern Oklahoma. There, "black middens"

began to form in Late Archaic times. The Fourche Maline culture,

in part, represents an intensification of this settlement pattern

during the succeeding Woodland period. The presence of places with

dense refuse accumulations in Late Archaic times suggests that people

were becoming less mobile and staying in certain highly favorable

localities for extended periods of time.

Another interesting observation is that Late Archaic

peoples were making extensive use of local stones to make tools.

Why is this interesting? Because, except in areas such as the Ouachita

Mountains, most of the local stones in the Caddo area are of poor

quality and occur in small cobbles that are ill-suited to make nicely

finished stone tools (such as dart points, knives, and wood-working

tools). For instance, in parts of east Texas a commonly used material

was fossilized or petrified wood. The fact that Late Archaic people were using

such materials suggests two things. First, that they were not traveling

far to find serviceable, if minimally so, raw materials. Second,

there was not much trade with peoples in other areas (such as the

Ouachitas or central Texas) who had access to plenty of high quality

material.

Late Archaic peoples in the area appear to have been

hunters and gatherers as before, depending on a wide variety of

mammals, fish, birds, seeds, nuts, berries, and roots. Deer was

the most important large game animal, but the bones of many different

critters are found in Late Archaic middens. There is some evidence

for increased emphasis on the gathering and processing of nuts—especially

hickory. While hickory nuts are tough nuts to crack, their oily

meats are both flavorful and an important source of fat and protein.

Evidence for the increased reliance on hickory comes from the large

number of "nutting stones" (stones with small pitted cups

that held hickory nuts securely during cracking) and the frequent

recovery of charred nut hulls in Late Archaic sites. To extract

all the fat, the cracked hickory nuts were probably stone boiled

by dropping hot rocks into a nut and water slurry in tightly woven

baskets or skin pouches, and the fat is skimmed off the top.

In the Cypress Creek basin in northeast Texas evidence

has also been found for the use of roots—underground tubers

of the Psoralea family (common names include scurfy pea,

prairie turnip, and breadroot). Preparing tubers for eating is a

labor-intensive process. They had to be located, dug up, baked or

boiled, and then dried (or eaten immediately). The two advantages

of tubers are that they are available when nothing else is and that

they can be dried and stored for later use.

Putting all this together, across the Caddo Homeland

area we see evidence of people settling down into localized territories

and intensively using local resources, even those that were not

particularly desirable. This suggests that regional population levels

were high enough that there were no large unoccupied territories

into which people could easily move in tough times. People started

staying put or staying in smaller territories because their options

were limited. While we cannot point to any one Late Archaic site

and say with certainty, "This is where ancestors of the Caddo

lived," we have little doubt that Caddo ancestors were already

living in what would become their homeland. We also think that the

conditions were set for the cultural developments that were to take

place in the succeeding Woodland period.

|

San Patrice points from northeast Texas

and Oklahoma. From Johnson, 1989, courtesy Texas Historical

Commission.

|

Distribution of San Patrice points. From

Johnson, 1989, courtesy Texas Historical Commission.

|

"Watson Brake Archaic Mound Site,"

an interpretive charcoal sketch by Martin Pate. Courtesy National

Park Service, Southeast Archeological Center.

|

Flakes of novaculite from outcrops in the

Ouachita Mountains of southwest Arkansas. Novaculite was quarried

and used by prehistoric peoples in and near the Ouachitas

for thousands of years. Artifacts made of novaculite are occasionally

found in Archaic, Woodland, and Caddo period sites over much

of the Caddo Homeland. TARL archives.

|

Artist Terry Russell's depiction of a Caddo

woman and her child collecting seeds from goosefoot (Chenopodium

sp.), one of the starchy seed crops domesticated in the Eastern

Woodlands by 2000 B.C. Drawing courtesy of the Arkansas Archeological

Survey.

|

Nutting stones such as these from the George

C. Davis site are common in Late Archaic sites. The material

is ferruginous sandstone which outcrops locally. TARL archives.

|

Hickory nuts were an important food throughout

Caddo history and probably long before. These tough-shelled

nuts were high in fat and protein, but difficult to shell

and extract. Pitted "nutting" stones, such as those

shown here, are found in Archaic, Woodland, and Caddo sites.

Photograph by Frank Schambach.

|

|