In this section:

|

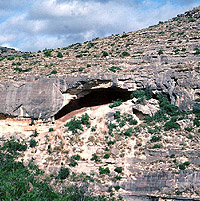

This small rockshelter is 41VV1—the

first formally recorded archeological site in Val Verde

County. It is one of hundreds of small shelters that

dot the Lower Pecos landscape. Prehistoric peoples found

these protected places useful for many different purposes.

This one is too small to have been lived in for long.

Photo from ANRA-NPS Archives at TARL.

|

|

As you read this, new rockshelters are forming ever

so slowly and old ones are crumbling. But most take

thousands of years to form, so you might not want to

wait around to watch.

|

This series of small rockshelters

occur near the top of a high cliff overlooking the Devils

River. The shelters have small, steeply sloping floors

and they face west, making these shelters unsuitable

for habitation. But they were used as rock art galleries.

If you look close in the center of the picture you can

see an archeologist standing in front of an impressive

rock art panel featuring a panther with a curly tail.

As you might guess, this site is known as "Curly-Tailed

Panther." Its unusual and precarious location suggests

that this place was the scene of special rituals perhaps

including "vision quests" or similar phenomena.

Photo from ANRA-NPS Archives at TARL.

|

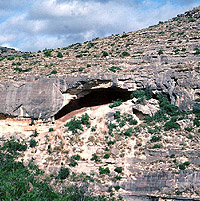

Hanging Cave, so named because it

seems to hang over this narrow channel, is also known

as No Goat Cave because it is one of few rockshelters

in the region that goats can't enter. This shelter is

larger than it looks and contains occupational debris

and several pictographs. Photo from ANRA-NPS Archives

at TARL.

|

Early morning excavations get underway

at Baker Cave, a large rockshelter located in a side

canyon of the Devils River. Archeologists gingerly make

their way down the steep rocky slope to the relative

safety of the cave. Photo by Tom Hester.

|

Eagle Cave, near Langtry, contains

thick deposits of occupational materials especially

cooking debris—burned rocks, charcoal, and ash.

Photo by Steve Black.

|

The lower Devils River valley as

viewed from the high cliff housing rockshelters with

pictographs. Photo by Steve Black.

|

Man stands in "sotol pit"

in Fate Bell Shelter, 1932. This large rock-strewn depression

is a roasting pit where sotol, lechuguilla, and probably

other plants were baked. There were several such pits

visible in the shelter when the archeologists arrived.

Photo from TARL Archives.

|

Excavations in progress at Baker

Cave, 1984. Photo from TARL Archives.

|

Archeologist Mark Parsons stands

in one of the many looter holes that left the interior

of Fate Bell Shelter looking like a World War I trench

warfare scene. The brown layers and patches are plant

fiber deposits of no interest to artifact collectors

but very informative for archeologists. The back of

the shelter is blackened by countless fires and also

covered in pictographs, so many that they were often

painted on top of one another. In fact, archeologists

began to determine the relative ages of different styles

of rock art by noting which style was covered by another.

Photo from TARL Archives.

|

|

Much of what we know about the ancient peoples

who lived in the Lower Pecos Canyonlands comes from rockshelters, places

where people sometimes lived and carried out both the mundane

and the sacred aspects of life. This section presents numerous

pictures of Lower Pecos rockshelters, explains rockshelter

basics, and introduces some of the better-known shelters.

What are rockshelters and how do they

form?

Rockshelters (or just shelters) are natural

overhangs or shallow caves that form on cliff faces and other

steep rocky exposures. They can form through wind erosion,

water erosion, and the dissolution of soft layers of rock.

Technically, rockshelters are wider than they are deep and

caves are deeper than they are wide, but this distinction

is frequently ignored. Many rockshelters are called caves

and we tend to use whatever name has stuck. The prehistoric

peoples of the Lower Pecos Canyonlands did make limited use of some true

caves also, but most caves in the area are not readily accessible

and are often very narrow, underground places ill suited for

human occupation. Rockshelters, on the other hand, often furnished

quite comfortable living quarters—big rooms with a view.

The Lower Pecos area contains hundreds of rockshelters.

They are common in the region for two reasons. First, the

right kind of rock—the area is part of a enormous expanse

of limestone called the Edwards Plateau that extends all across

the Texas Hill Country and beyond. Second, the vast network

of canyons provides the vertical rock faces needed for rockshelters

to form. The process of rockshelter formation can be complex

and it differs from spot to spot depending on such factors

as the direction the cliff faces, the prevailing wind direction,

the hardness of each rock formation, the distance to the nearest

stream, and so on. It is a continuous process that happens

on a geological time scale. As you read this, new rockshelters

are forming ever so slowly and old ones are crumbling. But

most take thousands of years to form, so you might not want

to wait around to watch. If you could, here is what you would

see.

In the Lower Pecos Canyonlands, rockshelters often form

in places where a layer of softer rock is sandwiched between

two harder layers. Because the softer materials erode faster

when exposed to the natural elements (wind, sun, and water),

a hollow begins to form. The hard layer above becomes the

roof of the rockshelter and the hard layer below becomes its

floor. As the back of the shelter and its roof weathers, "spalls"

or chunks of rock break off and fall to the floor of the shelter.

In cold wet winter weather, the process speeds up. Moisture

in cracks in the wall or roof expands when frozen and then

contracts when thawed. This cycle—expand, contract, expand,

contract—causes more spalls to break off from the roof

and wall and the rockshelter becomes larger and deeper. Eventually,

the hard layer that forms the roof becomes undercut too much

by the deepening shelter and the whole layer may collapse,

destroying the rockshelter.

Most of the rockshelter formation process actually

occurs at a microscopic level—tiny particles of rock

constantly trickle down, faster in soft rock, slower in hard

rock. These tiny particles form "cave dust"—a

fine off-white powder resembling unbleached flour. The spalls

and cave dust fall to the floor of the rockshelter. What happens

next depends on where the rockshelter is located and whether

its floor is flat or sloping. Some shelters have floors that

are steeply sloped outward such that anything falling on the

floor quickly tumbles to the canyon floor. Other rockshelters

have more or less flat floors and as roof spalls and cave

dust falls, it accumulates on the floor. Unless, that is,

the rockshelter is located at the base of a cliff beside a

stream, where anything resting on the floor is periodically

scoured out by floodwater.

Now for the part that draws the archeologist—the

stuff inside the rockshelters and on the walls. Many of the

occupied rockshelters in the Lower Pecos have more or less

flat floors and are located high above flood level. In these

places, the rockshelters slowly fill up with deposits of natural

materials— roof spalls and cave dust, mixed with cultural

materials—anything humans make or bring in. And people

living in rockshelters hauled in plants, tools, tool-making

materials, containers, food, rocks, firewood, and more. Over

time, some rockshelter deposits have grown to over 30 feet

thick just during the time span that humans lived in the region

(the last 13,000 years or so). Archeologists get excited when

we excavate rockshelters because we often find well-preserved

organic materials (see below) and as we peel back the layers,

one by one, evidence comes to light from earlier and earlier

periods of time. That, and the fact that the shelter walls

are often covered with bright multi-colored pictographs depicting

animals, humans, and many symbols whose meaning is not obvious.

Why were some rockshelters occupied and

not others?

As the photographs in this section show, no

two rockshelters are the same. Some are much larger than others,

some occur at the bottom of a cliff, others at the top, and

so on. In general, people, of course, chose to live in the

larger ones located near areas where water, food sources,

and other basic necessities were readily available. They favored

those with flat floors and those that faced in certain directions.

And this would have changed from season to season. For example,

in the hot summer, a rockshelter that faces (opens toward)

the west and the setting sun is not a very comfortable place

to be. Similarly, in the winter, shelters facing north are

much colder and windier than those facing south. This probably

explains why the rockshelters with the most abundant evidence

of occupation are those that face east or south.

We know which rockshelters were favorite places

to stay because they are full of evidence of daily life—trash,

mostly. And in the rockshelters of the Lower Pecos Canyonlands the trash

contains all sorts of organic materials that are not preserved

in most archeological sites. Dried plants, fibers, seeds,

nuts, leaves, roots, sticks, bone, leather, wood, and all

kinds of things made out of these materials. Baskets, mats,

ropes, nets, blankets, robes, digging sticks, atlatls, darts,

fire-drills, snares, pouches, sandals, and many more "perishable"

artifacts. We also find cooking pits, grass beds, latrines,

warmth hearths, and other kinds of features. Such things can

last for 5,000 to 6,000 years in the right environment. In

the Lower Pecos this means a well-protected rockshelter that

stays dry.

One of the things that people routinely did

in certain rockshelters was to cook plant foods—roots

and bulbs mostly—in large cooking pits called roasting

pits or earth ovens. Earth ovens are layered arrangements

of heated rocks, plants, food, and earth that roast or bake

food slowly—often over 2-3 days time. Not just any food,

but mainly root foods like the hearts (bulbs) of the lechuguilla

and sotol plants—inedible raw, after prolonged cooking

they turn to a sugary carbohydrate. Most earth ovens were

constructed outside in open sites archeologically identified

as burned rock middens—piles of fire-cracked rock that

accumulated around roasting pits. But in the Lower Pecos Canyonlands,

earth ovens were also built inside certain rockshelters. Why?

The most likely explanation is the shelters mainly were used

for cooking during periods of wet or very cold weather when

earth ovens would be difficult to build in the open.

Other shelters weren't used for everyday living

or cooking, but for special purposes. For example, there are

a series of shallow rockshelters located almost at the top

of an enormous cliff overlooking the Devils River. Most of

these are small and they have steep floors where nothing rests

for long. While these were useless as places to live, their

walls are covered with rock art. These were obviously special,

sacred places where rituals took place or were at least evoked

by the painted symbols such as that of a panther with an unnatural

"curly" tail.

When you visit one of these hard-to-reach places

high above the canyons, the view is spectacular and awe-inspiring.

It doesn't take much imagination to conjure up the "vision

quests" and other extraordinary experiences that small

groups of prehistoric peoples took part in there. While we'll

never know the details, we can see patterns in the location

of such places, the types of associated symbols, and sometimes

artifacts.

Another type of special purpose rockshelter

is that used for human burials. Sometimes burials are found

in ordinary rockshelters full of evidence of everyday life.

The burials are usually placed in the backs of the shelters

or in small chambers or other out-of-the-way places. In other

cases, people sought out small, remote shelters and crevices

as burial places, perhaps in hopes these would not be disturbed.

Lower Pecos Rockshelters

Fate Bell Shelter was one of the first

rockshelters in the Lower Pecos Canyonlands to be excavated by a professional

archeologist. A.T. Jackson carried out relatively modest excavations

there in 1932 on behalf of the University of Texas and its

archeological leader, Professor James E. Pearce. His excavation

report was the first reasonably detailed description of a

rockshelter. Several years later he published a study called

Picture Writing of Texas Indians that described the

pictographs found at Fate Bell and dozens of other localities

in the Lower Pecos and elsewhere in Texas.

Fate Bell Shelter is massive, stretching over

150 yards from one "end" to the other, but narrow,

only 40 feet or so at its widest point. It was used as an

habitation site, a cooking place, a burial place, and as a

rock art gallery. The thick deposits once contained a wealth

of information, but, sadly, most of the cave was dug up by

untrained people intent on finding showy artifacts. In the

1970s the property became part of Seminole Canyon State Park

and the site is now protected by law. Visitors to the park

can take special guided tours of Fate Bell Shelter, an unforgettable

experience.

Hinds Cave, located in a side canyon

off the Pecos River, is one of the most carefully studied

rockshelters. It was excavated in the 1970s by archeologists

from Texas A&M. They were particularly interested in human

ecology—how people interact with the environment. Professors

and graduate students undertook many different kinds of specialized

studies. One of the most informative types of research was

coprolite analysis. Coprolites are dried human feces—when

"reconstituted" by adding water, even 4,000-year-old

specimens smell just like the original. This may be more than

you wanted to know, but coprolite analysis gives a direct

picture of the ancient human diet. You won't be shocked to

learn that it was the graduate students who were assigned

to analyze the coprolites.

Baker Cave is on a small side canyon

off the Devils River. It, too, has been carefully studied

by several different projects. One of the most astonishing

findings there was a large cooking hearth that dates to about

9,000 years old during what is often called the Late Paleoindian

period. The hearth was chock full of bones, but not the bones

of bison or other large animals. Instead, there were snakes,

rats, fish, rabbits, and many other small creatures as well

as various charred seeds and nuts. This shows that by this

time people were already making use of virtually everything

that was edible.

Bonfire Shelter in Mile Canyon, a short

box canyon that empties directly into the Rio Grande near

Langtry, is probably the most famous Lower Pecos rockshelter.

It is famed because it was the scene of a series of buffalo

"jumps" beginning as early as 12,000 years ago or

maybe even earlier. You can read all about it in the Bonfire

exhibit.

Panther Cave is a "high lonesome"

shelter situated on a cliff overlooking the Rio Grande at

the mouth of Seminole Canyon. This cave is known for its spectacular

rock art, especially a huge red panther (mountain lion). This

site lies within the boundaries of the Amistad National Recreation

Area and is protected by federal law. It is managed jointly

by the National Park Service and the Texas Parks and Wildlife

Department. With a good pair of binoculars, the famous panther

can be seen from the scenic overlook trail in Seminole Canyon

State Park. When lake levels allow, special guided tours can

be arranged through Seminole Canyons State Park. Sadly, vandalism

forced the NPS to erect a heavy chain link fence to protect

the cave.

Coontail Spin Cave is a relatively small,

narrow rockshelter that is important because of the archeological

excavations done there in 1962. According to archeologist

Ed Jelks who supervised the Amistad Reservoir investigations,

the shelter takes its name from the local nickname for the

western diamondback rattlesnake—coontail—the dark

bands around the snake's tail are reminiscent of a coon's

tail. The "spin" describes the winding trail the

archeologists followed up and down the canyon walls to reach

Coontail Spin Cave. The results of work at this site will

be featured in a future exhibit on Texas Beyond History.

White Shaman Cave is a very small rockshelter

on a tiny side canyon of the Pecos River, not far from the

Pecos River Bridge. Small perhaps, but this shelter is famous

because of the evocative image of … you guessed it, a

white shaman. Actually, the "white shaman" is an

anthropomorphic figure of the type called "shamans,"

but the meanings of these figures are debated. (See

Rock Art.) This site is now owned and protected by the

Rock Art Foundation and can be visited on one of the regularly

scheduled tours. The climb in and out of White Shaman Cave

is not for the faint of heart, but the vivid pictographs and

intimate setting are truly remarkable.

|

Rockshelters form in limestone cliffs

and vertical faces where softer or fractured layers

of rock occur. These layers erode faster than the harder,

more resistant surrounding rock and, over time, become

prominent shelters such as this one. Photo from ANRA-NPS Archives at TARL.

|

The Curly-Tailed Panther painted

on the rear wall of an almost inaccessible rockshelter

high on a cliff overlooking the Devils River. Photo

by Steve Black.

|

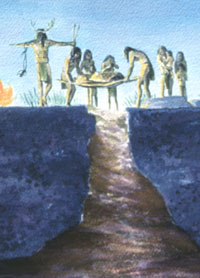

This scene depicts a burial at Seminole

Sinkhole, a natural cave formed by a solution cavity

in the limestone bedrock. Such places probably had great

symbolic importance as openings to the underworld. The

deceased was lowered into the narrow sinkhole opening

perhaps with the idea that in doing so, he or she could

join ancestors in the world beyond the living face of

the earth. Mural by Nola Davis, courtesy of the Texas

Parks and Wildlife Department.

|

Excavations underway at Coontail

Spin Cave in 1962. Access to this cave was extremely

challenging because of its remote location. Archeologists

reached it by descending a long, steep slope from the

opposite canyon wall and then climbing up a narrow tortuous

path to the cave. Photo from ANRA-NPS Archives at TARL.

|

|

Over time, some rockshelter deposits have grown

to over 30 feet thick just during the time span that

humans lived in the region.

|

Even at a distance, a trained eye

can spot the tell-tale signs of intense human occupation.

The gray fan-like talus deposits below this rockshelter

may look like the result of mining, but this is actually

cooking debris—literally tens of tons of fire-fractured

limestone rocks mixed with charcoal and ash. These "burned"

rocks are spent cooking stones rejected after they broke

into pieces too small to be useful. They are the result

of the use of this shelter for earth oven cooking on

countless occasions. For scale, the opening of this

shelter is about 10-12 feet high and perhaps 50 feet

wide. Photo by Phil Dering.

|

Fate Bell Shelter in Seminole Canyon

is one of the largest rockshelters in the Lower Pecos.

It was partially excavated by A.T. Jackson in 1932 and

briefly tested by Mark Parsons in 1963. In between and

afterward, much of the cave was churned up by looters.

The walls of the shelter are covered with hundreds of

pictographs. Today this shelter is protected within

Seminole Canyon State Park. It can be visited on regular

tours led by the Park Rangers. Photo courtesy of Texas

Parks and Wildlife Department.

|

Hinds Cave is located on a side canyon

off the Pecos River. It was excavated by archeologists

from Texas A&M University in the 1970s. Photo by

Phil Dering.

|

Fiber layers in upper deposits at

Baker Cave. This is typical of many of the dry caves

in the Lower Pecos Canyonlands. The upper deposits, 2-6 feet thick,

are mainly plant fiber from food refuse, bedding, wooden

and fiber-tool making, etc. This presents a real problem

to the archeologist—what do you keep? The whole

deposit?

|

Archeologist Mark Parsons exposes

a fiber layer in an undisturbed area of Fate Bell Shelter.

The distinctly colored and textured layers visible in

the excavation wall represent different episodes in

the shelter's long history of intermittent human occupation.

Generally speaking, the dark layers are associated with

intense occupation, while the light colored layers are

mostly cave dust and roof spalls from periods when the

shelter (or just this part of it) wasn't used by humans.

Photo from TARL Archives.

|

|