Tools fashioned from animal bones.

The one on the left is a bison scapula (shoulder bone)

apparently used as a digging tool. The pointed bones

and antlers were used for stone-tool making, basket

weaving, and sewing. The deer mandible (jaw) at the

bottom is polished from contact with plants - perhaps

it was used to strip seeds from grasses. From the ANRA-NPS

collections at TARL. |

Fiber-wrapped rabbit mandible thought

to be a scarifier, an instrument used to let blood or

score the skin during tattooing. Quite a few of these

have been found. From the ANRA-NPS collections at TARL. |

Rounded stone with incised groove.

This artifact may have been used as a bola, With a long

length of leather cording wound through the groove,

the hunter could have hurled the stone at the prey.

From the ANRA-NPS collections at TARL. |

|

Bone awl, worn and polished from

use as a weaving tool. From the ANRA-NPS collections

at TARL. |

Fire hearth, a piece of wood used

in conjunction with a fire drill to start fires. From

the ANRA-NPS collections at TARL. |

Girl uses fire drill and hearth in

Lower Pecos rockshelter as envisioned by artist Reeda

Peel. |

The images on painted pebbles are

often difficult to make out. From the ANRA-NPS collections

at TARL. |

Painted pebble from the ANRA-NPS

collections at TARL. |

Woven band that was once part of

a tumpline. Fiber or leather cords were attached to

the ends of the band and used to secure carried burdens

such as firewood bundles. The woven band was placed

across the forehead, while the cords held the load secure

on one's back. This very old carrying technique is still

used today in rural areas of Mexico and Central America.

From the ANRA-NPS collections at TARL. |

Lightweight net carrying bags were

probably important for transporting plants and other

raw materials. From the ANRA-NPS collections at TARL. |

Woven mat fragment. From the ANRA-NPS

collections at TARL. |

This miniature netted pack frame

may have been used by a child. From the ANRA-NPS collections

at TARL. |

Plant fibers were often used to wrap

and reinforce wooden artifacts. From the ANRA-NPS collections

at TARL.

|

Wood shavings (walnut and oak) recovered by flotation from the 1985 excavations at Baker Cave. Present by the hundreds or thousands, these are the result of using chert flakes to make wooden tools inside the shelter. Photo by Ken Brown.

|

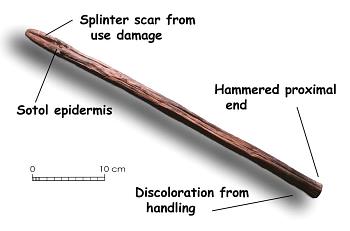

Closeup of distal end of hammered digging stick, showing dirt and sotol epidermis lodged in old splinter scar. Also note smoothing of splinter scar, and oblique scarring of the chisel-like blade. The history of this tool’s use is written on its face. Photo by Ken Brown.

|

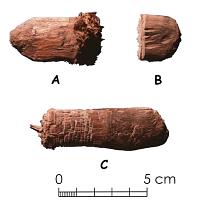

Three wooden artifacts from unidentified sites: A, hardwood wedge; B, tabular hardwood fragment (woodworking waste?), cut on one end by grooving and snapping, and on the other by chopping; C, rabbit stick fragment, an end amputated by chopping with a stone tool. The edges and end show battering, fraying, and other kinds of impact scarring. On the left end, transverse grooves produced by chopping probably served to anchor a sinew binding, now absent. Photo by Ken Brown.

|

|

In the dry climate and protected rockshelters

of the Lower Pecos Canyonlands, everyday things are extraordinary just

because they still exist today. Many, perhaps most of the

region's rockshelters have been dug into by artifact collectors,

treasure hunters, and vandals, wrecking most of the upper

deposits where perishable items are present. Archeologists

have partially excavated fewer than two dozen shelters in

the area, but these have yielded very important scientific

collections. Proper excavation of a rockshelter is tremendously

time-consuming because there are so many fragile and informative

things present in the deposits. And once the fieldwork is

over, much more remains to be done. Everything important must

be cleaned, catalogued, studied, identified, described, reported,

and then conserved and stored for posterity. Barring the unimaginable,

100 years from now the items you see here will still be available

to researchers for study.

As you look through the items here, think about

the fact that in most archeological sites in Texas, only things

made of stone survive. That is one reason why the surviving

Lower Pecos Canyonlands rockshelter deposits and the excavated samples

are so important—they preserve the details of prehistoric

life that are otherwise completely lost to us. Future Texas

Beyond History exhibits will take a detailed look at various

types of perishable artifacts from the Lower Pecos and explain

how they were made and used in the daily lives of the gathering

and hunting peoples of the region.

Rodent-gnawed fragment of a painted

cane flute. From the ANRA-NPS collections at TARL.

Plant stalk with branded design. From the

ANRA-NPS collections at TARL.

Drilled catfish inner-ear bone perhaps

used as an ornament. From the ANRA-NPS collections at TARL.

Late Archaic dart point with sinew binding

still attached. From the ANRA-NPS collections at TARL.

Bundle of fish-tail cactus spines tied

together. From the ANRA-NPS collections at TARL.

Ceramic figurine. Such objects are extremely

rare. From the ANRA-NPS collections at TARL.

|

Painted pebble from the ANRA-NPS

collections at TARL. |

Painted pebble from the ANRA-NPS

collections at TARL. |

Painted pebbles are common in the

Lower Pecos Canyonlands but examples are also known from the South Texas Plains and Edwards Plateau. They are almost always made on smooth, flat,

rounded pebbles that are elongated or oval in outline.

Although they share some elements with pictographs,

they are usually painted in black only. Archeologist

Mark Parsons believes these objects represent stylized

human beings (or human-like mythical beings) with the

smaller, pointed ends representing the head. Most likely,

these are female figures. He has defined six design

styles and believes these evolved over time through

a tradition that began around 8,500 years ago.

|

|

Painted pebble from the ANRA-NPS

collections at TARL. |

Painted pebble from the ANRA-NPS

collections at TARL.

|

Rabbit-stick wielding boys chase rabbits

toward a net fence and a certain fate. Mural and diorama scene

by artist Nola Davis, courtesy of Texas Parks and Wildlife

Department.

Fiber artifacts: Tough plant fibers from

plants such as yucca, lechuguilla, sotol, and beargrass were

used to make all sorts of everyday items. Sandals were essential

in this rocky land with cactus and thorns everywhere. Woven

mats were used as sleeping mats and to keep foodstuffs off

the dusty cave floors. Woven baskets were used as containers.

Twined cord was used for many purposes including net bags

and long nets used to catch rabbits as shown in the above

mural scene.

Wide woven strip. From the ANRA-NPS collections

at TARL.

The bottom portion of a large basket that

was tightly woven and sealed with pitch or resin to make it

water-tight. From the ANRA-NPS collections at TARL.

Wooden Artifacts: Although the Lower Pecos landscape is largely treeless except in draws and riverine corridors, most of the tools used in prehistory were made of wood or had substantial wooden components. Tiny wood shavings — recovered in the thousands by flotation of matrix samples from dry shelters — attest to manufacture of wooden tools in sheltered base camps, using nothing more elaborate than a sharp chert flake. There are also chopped billet sections, grooved and snapped sticks, split sticks, trimmed sections of native cane, split and sawn flower stalk sections, tenoned sticks, wooden pitch daubers, and wooden wedges (for splitting larger pieces of wood). These represent manufacturing waste or tools for making other artifacts. In addition to cutting with sharp flakes, woodworking techniques included chopping, splitting, grooving and snapping, snapping without grooving, planing, drilling, incising, abrasion, burning, and firehardening. Stone adzes and reduction of wood by adzing seem to have been quite rare.

Hammered digging stick made of persimmon wood, probably from Painted Cave (41 VV 90). Termed “mescal chisels” in the Southwest, these were hammered (with a rock) into the rootstocks of sotol, lechuguilla, or yucca plants, then used as a lever to pry the plant out of the ground. This one has a frayed proximal end from hammering, a splinter scar from impact against rocky ground, discoloration from handling by its owner, and sotol epidermis and dirt lodged in the scar. Photo by Ken Brown.

There are extractive (or food-getting) wooden tools such as unspecialized digging sticks; hammered digging sticks (“mescal chisels”) used to sever the rootstocks of sotol, lechuguilla, or yucca plants and pry them up; rabbit sticks (including impact-split or amputated fragments); atlatl fragments (complete ones are very rare); hardwood atlatl dart foreshafts and mainshaft fragments (native cane or flower stalks); bow fragments; hardwood arrow foreshafts (often impact-splintered); arrow mainshaft fragments (made of native cane); scissors snares (made of wood and fiber cordage), and pointed sticks which could possibly represent parts of trigger assemblies for stone slab deadfalls. There were netted pack frames (conical wooden frameworks with fiber cord netting and woven backmats, rare but occasionally found in mortuary contexts) used for collecting and transporting goods. A wooden mortar and pestle found in a cave near Pandale represents a unique item. Fashioned from a section of tree trunk by charring and scraping, it contained some cactus seeds lodged in cracks in the wood. “Mescal knives,” large ovate to triangular unifacially retouched flakes used for cutting rootstocks of sotol, lechuguilla, or yucca, have occasionally been found hafted in sturdy wooden handles.

Among the wooden artifacts are also maintenance tools (fire drills and fire drill hearths, scoops, stakes, awls) as well as items that may have served social or ritual functions — musical rasps, cane flute or flageolet fragments, wooden beads, possibly wooden bullroarers, and painted sticks. Mineral pigments such as pyrolusite (black manganese dioxide), limonite (yellow hydrous iron oxide), and possibly hematite (red iron oxide) have been identified on paint sticks from the Shumla area in the Witte Museum collections. Tubes made of native cane, packed with juniper needles and scorched on the end, seem to resemble the cane tube cigarettes known from Arizona and New Mexico. Uncommon, but present, are some small items that were probably made by adults for children as devices for economic training — miniature scissors snares, bows, and conical netted pack frames, the first two presumably used by boys and the last by girls. There are also infant cradles made of wood and cordage.

Although a few wooden artifacts (like the mortar and pestle) are known to archeologists because they were cached in shelters for future use or were left as mortuary items, many more are present in sheltered base camps because they failed. Impact-shattered arrows, snapped digging sticks, smashed deadfall bait sticks, broken atlatls, and scissors snares with broken draw cords are examples. Many of these failed during field use, but were returned to base camps because they had salvageable parts or could be recycled into some other kind of artifact. Because wood is so much more impressionable than stone, many of these items have extensive usewear histories embedded on their surfaces. Digging sticks have hand polish and discoloration from use as walking sticks while traveling to forage areas. There are scars on the tip from contact with rocky soil, and “fulcrum dents” showing where the sticks were levered against rocks to pry plants out of the ground. Impact splinters are common, and the scars left sometimes bear dirt and bits of plant tissue embedded when the stick was last used. Clues like these furnish details of prehistoric behavior that are difficult to glean from stone tools.

To see many more images of artifacts from the Amistad National Recreation Area, visit the National Park Service Museum Collections.

|

Prickly pear pad pouch with a carrying

loop. Large pads were split or hollowed out and used

as containers. From the ANRA-NPS collections at TARL. |

Carved and drilled animal bones,

perhaps used for personal or ritual purposes. From

the ANRA-NPS collections at TARL. |

Lechuguilla spine apparently used

as natural sewing needle with built-in fiber thread.

From ANRA-NPS collections at TARL. |

Stick threaded into natural groove in large fish vertebrae.

This is one of many objects for which there is no obvious

explanation. From ANRA-NPS collections at TARL. |

|

Scissors snare used to trap small

animals. It is about 9 inches long. From the ANRA-NPS

collections at TARL. |

|

Small digging stick about 20 inches

long. From the ANRA-NPS collections at TARL. |

Painted pebble from the ANRA-NPS

collections at TARL. |

Miniature sandal perhaps made for

a child. From the ANRA-NPS collections at TARL. |

Fragment of a large mat woven out

of yucca fibers. Such mats were common in the Lower

Pecos and probably helped keep food items free from

cave dust. From the ANRA-NPS collections at TARL.

|

Sandals were often made of lechuguilla

leaves which provided the toughest fibers of all the

available plants. From the ANRA-NPS collections at TARL. |

Small sandal from the ANRA-NPS collections

at TARL.

|

General-purpose digging stick from 41 VV 66, broken into two sections. The surviving parts fit together at 89 cm in length, but one end is missing. Note the long splinter scar, and staining on the shorter section. Cooked plant residue suggests the stick may have been used to open an earth oven shortly before it was cached or discarded. Photo by Ken Brown.

|

Closeup of tip of general–purpose digging stick. Smoothing and polish on splinter scar shows the tip was resharpened and usage continued even after the splinter broke away. Photo by Ken Brown.

|

Dart foreshaft (wood species unknown) from 41 VV 156. Photo by Ken Brown.

|

|