Major battles of the Red River War

Courtesy of the Texas Historical Commission.

|

Portion of an 1875 map showing the

general location of the Battle of Red River. Courtesy

of the United States National Archives.

|

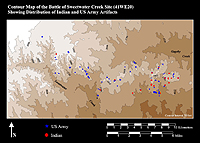

Contour map of the Battle of Sweetwater

Creek site showing the distribution of U.S. Army and

Indian artifacts. Courtesy of the Texas Historical Commission.

|

A Kiowa ledger drawing possibly depicting

the Buffalo Wallow battle. Courtesy Texas Memorial Museum.

|

Captain Wyllys Lyman. Courtesy of

Panhandle-Plains Historical Museum.

|

Pony Tracks in the Buffalo Trails by Frederick

Remington. Courtesy of the Amon Carter Museum. |

Lone Wolf, Kiowa Chief. Courtesy of Panhandle-Plains Historical

Museum. |

|

Though most of the battles of the Red River

War were brief skirmishes that involved a small number of

combatants and resulted in few casualties, a number of larger

and more significant battles also occurred. These include

the Battle of Red River, Sweetwater Creek, and Palo Duro Canyon.

The battles of Lyman's Wagon Train and Buffalo Wallow also

are notable.

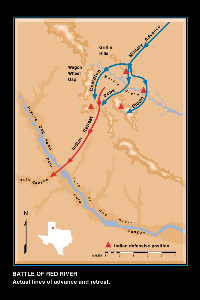

The first battle of the Red River War came on

August 30, 1874, when troops of the Sixth Cavalry and Fifth

Infantry under the command of Colonel Nelson A. Miles caught

up with a large group of Southern Cheyenne near the Prairie

Dog Town Fork of the Red River in what is now southern Armstrong

and northern Briscoe counties, Texas. The military records

describe the daylong Battle of Red River as a running battle

across the rugged canyonlands north and south of the river.

Though the Army soldiers numbered some 650 strong with two

Gatling guns and a 10-pounder Parrott rifle, the Indians were

able to hold them off long enough for the Indian families

to safely escape up Tule Canyon and vanish across the Staked

Plains.

A week earlier, Major William R. Price and companies

C, H, K, and L of the Eighth U.S. Cavalry had left Fort Union,

New Mexico, and headed east toward the Texas Panhandle as

the westernmost column in the campaign against the Southern

Plains Indians. The column consisted of 216 soldiers and included

two mountain howitzers and a large supply train. Crossing

the Texas Panhandle south of the Canadian River, the column

followed the old Fort Smith-Santa Fe Road. On September 4,

Price divided his command, directing Captain Farnsworth to

take H company, all of the wagons, and one howitzer toward

Adobe Walls to establish a supply camp near there.

Major Price took C, K, and L companies and one

howitzer as the main column. On September 12, as the column

moved northeast between Sweetwater Creek and the Dry Fork

of the Washita River, they encountered a large band of Kiowa

and Comanche Indians led by Kiowa chief Lone Wolf. The ensuing

engagement, known as Price's Engagement or the Battle of Sweetwater

Creek, took place along a high ridge north of Sweetwater Creek

in present Wheeler County, Texas.

Though Major Price and the soldiers were not

aware of it while the battle was occurring, a large number

of Indian families apparently were behind the high ridge trying

to evade the troopers and make their escape to the southwest.

The Indian warriors likely were trying to lead the troops

away from the women and children and were trying to keep the

troops occupied long enough to give the families time to escape,

which they did successfully. The running battle lasted some

four hours and covered a distance of about seven miles.

Meanwhile, Miles had decided to establish his

headquarters camp on Red River and send a military escort

under the command of Captain Wyllys Lyman with 36 empty supply

wagons back toward Camp Supply in Indian Territory to restock

the provisions. Lyman's command consisted of 36 infantry,

20 cavalry, and 36 civilian teamsters, of whom only 10 were

armed.

On September 9, the train was returning to the

Red River with supplies when it was attacked by a group of

Kiowa and Comanche warriors at the divide between the Canadian

and Washita rivers. The Indians began firing from long range,

but the defensive maneuvers of the cavalry enabled the train

to move 12 miles farther south until it reached a steep ravine

about a mile north of the Washita River. As the train approached

the river, the Indians began to press the attack and Lyman

ordered the wagons to form into a protective corral for better

defense.

As the train was circling, a group of about

70 warriors attacked from the right and rear of the train

and almost overran the skirmish lines that had been established

by the infantry. The skirmishers held and repulsed the attack

but a sergeant named DeArmond was killed during the assault

and Lieutenant Granville Lewis was severely wounded. One of

the teamsters, a man by the name of Sandford, was mortally

wounded while carrying ammunition to the troops. When the

initial attack failed, the Indians retreated to the surrounding

ridges and began to lay siege to the wagon train. It was later

learned that, in addition to Lone Wolf, several other prominent

chiefs also took part in the battle including Satanta and

Big Tree.

With the onset of darkness, the fighting fell

off, but it was now apparent to Lyman that the Indians intended

to continue their siege for an indefinite period and he ordered

the men to dig rifle pits around the perimeter of the circled

train to afford additional protection for the men. The next

morning the Indians resumed their fire. On the night of September

10, seeing that the situation was desperate, Lyman sent one

of the scouts, W. F. Schmalsle, to Camp Supply to get help.

As he left the wagon train, Schmalsle was chased by the Indians

but he managed to evade them and he arrived at Camp Supply

two days later. On the morning of September 12, the Indians

began to abandon the siege.

Later in the afternoon, a cold rainstorm set

in and continued through the next day. Even though the command

was almost out of supplies, Lyman decided not to try to move

the train in the storm. Several of the horses had been injured

and 22 mules for the wagons had been killed. In the early

morning hours of September 14, Company K arrived from Camp

Supply with medical aid and an ambulance. With the siege broken,

Lyman moved out with the wagons and later that morning joined

Colonel Miles. On the recommendation of Colonel Miles, 13

of the troopers were awarded the Medal of Honor for their

bravery in the fight and Lyman was eventually promoted for

his performance.

On the morning of September 12, 1874 about 125

of the warriors who had laid siege to the Lyman wagon train

decided to move south of the Washita River to join their families.

As the warriors reached a small rise north of Gageby Creek

they ran into a small detachment of six men from Colonel Miles'

command who were riding with dispatches and were charged with

locating Lyman's wagon train. The detachment consisted of

civilian scouts Billy Dixon and Amos Chapman and four soldiers

of the Sixth Cavalry. The ensuing engagement between the warriors

and the six men has come to be known as the Battle of Buffalo

Wallow.

The Indians quickly encircled the couriers,

stranding them with essentially no cover. The little group

of men dismounted and prepared to fight. A Private Smith was

given the horses reins to hold. Within moments of the battle's

outbreak he was shot in the chest and fell to the ground as

the horses stampeded.

After about four hours of the Indians taunting

and firing at them, all of the whites except Dixon had been

wounded. He spotted a small buffalo wallow, a shallow depression

on the plain. Determined to make use of what little cover

there was, Dixon made a run for the wallow, and three of the

other men quickly joined him. Once there, the men began digging

with knives to deepen the depression, throwing the sandy soil

up as a breastwork around the perimeter of the wallow. The

two men who remained outside the wallow were Private Smith

who had been shot first and was believed dead, and Chapman

who had suffered a crippling wound to his leg. After several

attempts, Dixon was able to reach Chapman and carry him back

to the wallow.

As the afternoon wore on, the men began to run

low on ammunition and it was decided that the revolver and

ammunition belt should be retrieved from the body of the dead

Private Smith. One of the soldiers, a Private Rath, ran to

the motionless body and recovered the items, but when he got

back to the wallow he reported that Private Smith was still

alive. Dixon and Rath made their way back to Smith and carried

him back to the wallow, but it was obvious that he would not

survive. "We could see that there was no chance for

him. He was shot through the left lung and when he breathed

the wind sobbed out of his back under the shoulder blade,"

Dixon wrote in his memoirs. Later that night Private Smith

died in his sleep.

By mid-afternoon a storm came up and a heavy

rain began to fall. As miserable as the men were in the buffalo

wallow the storm had an unseen benefit. With the advent of

the inclement weather, the Indians broke off the fight and

disappeared into the night.

The next morning Dixon left the wallow on foot

to try to find help for the wounded men. After a short while,

he encountered the Eighth Cavalry under Major Price's command.

Upon learning of their situation, Colonel Miles had the men

rescued. Although all six men were awarded the Congressional

Medal of Honor, Dixon's and Chapman's were later revoked because

they were not officially enlisted in the Army. In 1989, the

Army Board for Correction of Military Records restored the

medals to Dixon and Chapman.

The critical battle of the Red River War began

as the sun rose on September 28, 1874. At least five Indian

villages had sought protection in the hidden isolation of

Palo Duro Canyon. Then Colonel Ranald S. Mackenzie, in command

of the Fourth Cavalry, charged into the canyon. With their

people scattered, Indian leaders Iron Shirt of the Cheyenne,

Poor Buffalo of the Comanche, and Lone Wolf of the Kiowa could

not mount a united defense and fell back before the onrushing

horsemen. The soldiers captured and burned the villages, including

the Indians' winter food supply. They also captured 1,424

Indian horses that they drove some 20 miles from the scene

of the fight where they killed more than 1,000 of the horses

to prevent them from being retaken by the Indians.

After this battle, with no provisions to see

them through the winter and with no horses, many of the Indians

began to drift back to the reservations. Over the next several

months, the U.S. Army would sweep the remaining Indian holdouts

from the Texas Panhandle and force them onto the reservations.

Thus ended the Indian War on the Southern Plains.

|

A metal arrow point (left) and knives

used by the Indians at the Battle of Lyman's Wagon train.

Click images to enlarge

|

Lines of U.S. Army advance and Indian

retreat at the Battle of Red River site.

|

Artifacts from the Battle of Sweetwater

Creek: shot from Howitzer canister; a priming wire;

and a friction primer. Photo courtesy of the Texas Historical

Commission.

|

Colonel Nelson A. Miles, Fifth Infantry.

Courtesy of Panhandle-Plains Historical Museum.

|

Comanche chief Mow-Way participated

in several of the Red River battles.

|

Major William R. Price, Eighth Cavalry.

Courtesy of Paul V. Long.

|

A U.S. Cavalry button.

|

Colonel Ranald S. Mackenzie, Fourth

Cavalry. Courtesy of Panhandle-Plains Historical Museum.

|

|