Transitions of a Freedman Farm Family

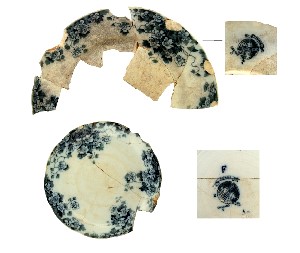

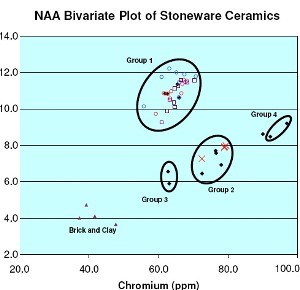

The story of how Ransom and Sarah Williams, through hard work and perseverance, made their way up from slavery, through the Reconstruction period, into the Jim Crow era and to the time they left the farm early in the twentieth century, is a post-emancipation success story of a kind not found in other Texas historical narratives. This was a period of tremendous changes for African Americans as they became citizens, landowners, businessmen, paid laborers, craftsmen, and consumers. When viewed in light of historical documents and records, the archeological materials recovered from the farmstead provide tangible evidence of these transitions and the success of this freedman family in central Texas. Amid the thousands of artifacts and farmstead remains, we also find poignant expressions of the family’s traditions and values—and even echoes of their distant African ancestry. Ransom Williams purchased his 45-acre farm in 1871, and he likely lived alone for a few years before marrying Sarah Houston, sometime around 1875. In these early years, Ransom began clearing some of his land for cultivation, building rock fences for his livestock, and working on his log cabin. He probably completed the construction of the house before he and Sarah were married, and their first son, Will, was born in 1876. While Sarah took care of the child and did the cooking, mending, gardening and other chores, Ransom worked the pastures and agricultural fields, tending to his livestock and crops. The family grew over the next two decades, and Ransom and Sarah worked hard at raising nine children on the family farm. The Williams farm was situated in a thin-soiled, rocky upland—the type of land not particularly conducive to farming. But hard work and careful attention to the land and the crops could ensure a successful yield each year as long as rainfall was adequate. As former slaves, Ransom and Sarah were not strangers to hard work. Most likely, Ransom had been a slave on the Bunton plantation in northern Hays County, and he probably knew first hand the labor involved in planting and picking cotton, how to care for livestock, including horses, and how to do other farming tasks under less than ideal farming conditions. Historic records and the artifacts found on the farmstead prove that hard work did indeed pay off for the Williams family. Their success can be traced in tax records and in the consumer goods they purchased during the three decades they spent on the farm. On a larger scale, these reflect the family’s transitions from self-sufficient farmers to participants in the rapidly changing American economy. The Williams Family as American ConsumersIn the early 1870s, having just purchased the farm and gotten married, Ransom and Sarah Williams would not have had much extra cash. During this time, the farm operation was probably geared toward home production and self-sufficiency. The family produced and made most of what they needed on the farm, but they had little extra to sell and probably purchased outside goods from other farmers or commercial businesses only when absolutely necessary. As time passed and they became more successful, the Williamses continued to purchase the necessities of farm life, but they also spent more of their extra income on nonessential items and even some things that would be considered luxuries. As the Williams family grew, however, there were more mouths to feed and children to clothe. There is no doubt that the Williamses had to have had a steady source of income to simultaneously raise their children, increase their farm productivity, and acquire the material wealth that is evident in the archeological record. During the last quarter of the nineteenth century, America was experiencing an economic boom resulting from the mass-production of goods, the rapid spread of rail transportation, and widespread consumer-oriented product advertising. All types of goods could be manufactured more quickly and efficiently, shipped more easily, and sold more cheaply than ever before. Prices dropped and availability increased. The railroad had come to Austin in 1871, just as Williams was buying his farm, and it turned the capital city into a regional market hub. They might have been able to shop in some general stores in small communities that were closer to their farm (such as Manchaca Springs), but the Williamses most likely made occasional journeys to Austin by horse or wagon. The Williams farmstead was about a dozen miles from Austin as a crow flies, and more than 15 miles by wagon roads. A round trip by horse would have taken most of a day, while a round trip by wagon would probably have taken the better part of two days and required an overnight stay. In 1880, the International & Great Northern Railroad was completed from Austin to San Marcos, and the small communities along the route began to blossom and thrive. The town of Manchaca Springs was relocated about 2.5 miles east of the Williams farm. This meant that Ransom Williams could make a quick trip into town, by horse or wagon, to get supplies. The proximity of the railroad at Manchaca, as it came to be known, increased the Williams’ access to goods and services, as well as the family’s ability to get their farm products to markets. Mail Order Catalogs and Mass ProductionEfficient manufacturing technologies and a more extensive transportation network meant lower prices, and a vast array of durable goods became affordable for the masses, including farmers and laborers in the rural hinterlands. By the late 1880s, large retail companies such as Montgomery Ward & Co. and Sears Roebuck & Co. were selling a wide variety of products to consumers all across the country through their mail-order catalogs. These typically were available in general stores in small, rural towns. After the Civil War, people across America began shifting away from home production toward consumption of commercial products, but it seems the Williamses were still very much a part of both ways of life. In many ways, the Williams farm was always a self-sufficient operation, and the family probably produced a great deal of the food they consumed and the products they used in any given year. But as the family farm became increasingly successful, some aspects of the farming operation may have become more commercialized. Planting more cash crops brought in more income, and this money would have been used to pay taxes, buy essential farming tools and staple foods, and perhaps to purchase seeds for the next year’s crops. If there was any money left, it could be saved or spent on nonessential or luxury items. It is interesting, albeit somewhat tricky, to try to calculate how much income he might have netted each year and how much buying power he might have had. Ransom Williams managed to be excluded from all the population and agricultural censuses while he lived on the farm, and this may have been intentional if he wanted to stay out of the limelight. This exclusion means that we do not know exactly what crops he grew or how much money he made from the sale of particular cash crops. However, we can make an educated guess based on the records of his neighbors and data from the annual Agricultural Bureau Report. Based on the estimated prices paid for cotton and corn during the 1880s and 1890s in Travis and Hays counties, Ransom could have made somewhere between $155 and $200 annually. Likely half to three quarters of this amount would have been spent on consumable goods (food, medicine, tobacco, ammunition, etc.) and durable goods (fabric, buttons, tools, and equipment). The remaining money may have been as little as $40 or as much as $100, and this money, along with any other income Ransom and Sarah might have derived from doing odd jobs such as hauling, sewing, or gunsmithing, was discretionary money. This extra money—small by our standards today—represented a significant amount of buying power in the late nineteenth century. For Ransom and Sarah Williams, it represented the ability to purchase a few luxuries for themselves and their children, and a chance for them to participate in the great American dream. Judging from the recovered artifacts, it appears that the family’s purchasing power and consumption of commercial products increased significantly in the 1890s. Ransom and Sarah Williams clearly used some of their discretionary money—profit made from their successful farming operation—to purchase nonessential items, and they likely made some of their purchases through mail-order catalogs. Among the artifacts we matched with pictures in the catalogs are several musical instruments, a men's pocket watch, a Frontier Bull Dog revolver, a kerosene lamp with crysal glass base, ornamental items such as a ladies' brooch, jet buttons, a hair comb, and a variety of childrens' toys and school items. Despite their physical isolation, there is little doubt that the family soon became well entrenched in the burgeoning American consumer culture of the day. Making Choices and Expressing IdentityFor the Williams family, this new means of making choices and expressing identities may have been laden with symbolic as well as political meanings. In the view of archeologist and author Paul Mullins, people have always used material culture as a means of reinforcing their social status, group affiliation, and individual identities. To freedmen who had once been commodities themselves, the concepts of wealth, class, and social privilege were not at all foreign. In The Archaeology of Consumer Culture, Mullins posits: “African Americans understood the significant privileges vested in consumer citizenship, privileges many white consumers simply took for granted. The collapse of Reconstruction vanquished many of African Americans' partisan political ambitions and began a lengthy assault on their public rights, and this may have boosted the politicization of consumption among African Americans.” Many blacks were optimistic that free-market capitalism would eventually level the playing field, but others “tended to soberly acknowledge the deep rootedness of anti-black racism and believed that it was only in a largely insular black economy that African Americans might blaze their own path to self-determination.” As successful farmers and landowners, Ransom and Sarah Williams were able to build a good life for themselves and acquire some luxuries for the family. They did business with African American enterprises when possible. When they spent extra money on a matching set of china with an elegant floral design, imported from England and complete with a tea service (cups and saucers), it was an expression of their financial success and equality as American consumers. Owning such objects was for them, as it is for so many people today, a source of pride and a statement of identity. At the same time, however, Ransom and Sarah Williams probably had no illusions about their place on the social ladder in the Jim Crow South. When they ventured into public in the white world, they would have dressed conservatively and kept their displays of wealth to a minimum. Archeology and Social Identity: Who Were the Williamses?Ransom and Sarah Williams and their children cannot be lumped into a group represented by a single identity. Rather, like all peoples, their identities varied according to particular social situations. At different times, they would have been Americans, African American freedmen, Texans, central Texas farmers, horse breeders, business entrepreneurs, consumers, laborers, or Christians. At many times, the family’s identity would have been defined by a combination of their race and economic class, with their role as African American landowners being the significant criteria that defined their lives within the white Bear Creek community and the nearby freedmen communities at Antioch Colony and Rose Colony-Manchaca. Their identities also were shaped by the larger political structures that were controlled by white-run society, including the governments of Travis County, the State of Texas, and the United States. Amid these many transitions, there also is evidence the family held on to some of the old ways, perhaps derived from Ransom’s early years in the plantation South where cherished African folk traditions and spiritual beliefs were passed on from generation to generation and burnished in their memories. In this section, we examine some of the Williams family identities as revealed by the archeological investigations and recovered artifacts. Keepers of Tradition: The Southern Swept YardAlthough it was less intensively investigated than the house footprint or trash midden, the immediate yard area around the Williams house proved to be an important component of the farmstead. After comparing the artifact recovery rates across the house complex, we discovered that the yard area had an extremely low artifact density and yielded an abundance of small and fragmentary items. To explain this phenomenon, we proposed that the Williams family maintained a swept-earth yard, keeping it devoid of vegetation and regularly sweeping it to remove debris. The swept yard, a tradition that can be traced back to Africa and the Carribean, serves not only a practical function but carries symbolic and social meaning. Archeologists Barbara Heath and Amber Bennet note that the Bakongo of Central Africa believe that sweeping as a ritual gesture helps rid a place of undesirable spirits (see sidebar: The Southern Swept Yard). In his summary of African American archeology in the South, Virginia archeologist Fesler summarized the practice as follows: Sweeping a dirt yard bare around the house is a familiar practice today to most rural American Southerners, both black and white, although swept yards are especially prevalent in rural African-American home sites in the South. In fact, Southern whites likely adopted the practice of yard sweeping from African-Americans as Southern culture was creolized. The functional reasons for keeping a yard swept are numerous, including ridding the yard of insects, snakes, and other vermin, keeping the grass down to prevent brush fires, and providing a clean, orderly place for socializing out of doors, especially during the hot and humid summer months. The swept yard tradition was still practiced in central Texas into the 1930s and 1940s, as demonstrated in an oral history interview. Ruth Fears, who grew up in the Antioch Colony freedmen community 4.5 miles from the Williams farmstead, recalled: “We got out and swept the yard, swept the yard clean.” She also recalled using broom weed: “We’d get them and tie them around at the bottom and sweep the yard up. That’s what we swept the yard with.” Given the long history and significance of the swept yard tradition among Southern African Americans, it is not surprising that the Williams family practiced yard sweeping at their home. The archeological evidence suggests that they did this regularly over a long period of time. Exactly why they did this is less certain. As former slaves, it is likely that Ransom and Sarah would have been aware of the spiritual connotations of yard sweeping. Unfortunately, we know nothing of their specific African roots and can only speculate on the extent to which Ransom and Sarah believed they were sweeping away evil spirits. Perhaps this cultural tradition was important to them because it provided a connection with their ancestors. Or they may have simply wanted a swept yard to provide a safe place for young children to play and protect their home from brush fires. In any case, the original knowledge of the early practitioners has been lost, and people who keep swept yards today are often totally unaware of the spiritual connotations that yard sweeping once had. Believers in Ritual: The Dart Point in the Chimney FireboxA small artifact found inside the cabin provides further evidence of deeply held traditions among the Williams family. In terms of its symbolic meaning, it is intriguing that this artifact is not even a historic item but a prehistoric one. Archeologists uncovered a nearly complete chipped-stone dart point in the chimney. Clearly, it had been placed in the sand and rock layer at the bottom of the firebox for a particular purpose. Its context leaves no doubt that the dart point represents some type of ritual offering that was made when the chimney and house were being constructed. We believe that this dart point was a protective charm placed in the fireplace by Ransom Williams. The dart point may have had a relatively simple meaning, such as to bring good luck to the household, similar to what a horseshoe hung above a doorway means. Or its symbolism may have been deeper, perhaps representing an offering to honor the ancestors who lived on the land before, or a charm to keep evil spirits from entering the house through the fireplace. There are many examples of material culture used by African Americans as charms in religious, spiritual, or ritual contexts. Documented through oral history, archeological finds, or both, these types of offerings include: concentrations of sewing items and shiny objects associated with conjure bags; placement of particular objects into symbolic patterns (e.g., cosmogram); markings on artifacts (engraved cosmogram); coins worn in a shoe; coins (often dimes) with drilled holes worn as necklaces and ankle bracelets; exotic natural stones (crystals and polished rocks), and Native American artifacts (especially projectile points). In their 1997 article, Conjuring in the Big House Kitchen: An Interpretation of African American Belief Systems, Based on the Uses of Archaeology and Folklore Sources, Mark Leone and Gladys-Marie Fry note that chimneys and hearths were important locations within African American dwellings where ritual caches or bundles were frequently placed, citing cases in Virginia and Maryland. Collectively, a great deal of historical and archeological evidence indicates that windows, doors, and chimneys were thought to represent openings where evil spirits could enter or leave a house, and these were the spots were conjuring charms were placed. Although we will probably never know why Ransom Williams placed this dart point in the center of the firebox when he built his house, we can add this example to a growing list of archeological finds where Native American artifacts were placed in probable ritual contexts within African American households. This pattern appears to represent a belief system that was common among African Americans, and the special symbolism of Native American items and hearths are subjects that warrant more study. Bearers of American Patriotic SymbolsThree types of artifacts from the farmstead incorporate visual symbolism of the United States of America, and these objects may have been valued possessions in the Williams family because of this patriotic association. Two U.S. Army general service buttons were found; their faces are stamped with the classic image of a spread-winged eagle with a stars-and-stripes shield on its chest. The style of the eagle indicates they were manufactured between 1855 and 1884, and they may have been from a uniform that was used during the Civil War or surplus sold after the war. There is no way to know whether Ransom Williams acquired a U.S. Army jacket with the buttons on it, or only acquired the military buttons. It is reasonable to assume, however, that he would have been aware that these button were the same style worn by the Union soldiers who helped emancipate the enslaved African Americans. He would also have been aware that regiments of African American soldiers, some northern freedmen and some escaped Southern slaves, had fought for the Union and wore these buttons. As a former slave who was probably 19 years old at emancipation, Williams may have believed that these military buttons were symbolic of freedom and thus an important possession. The second artifact bearing a patriotic symbol is the cheek plate of a snaffle bit with a distinctive U.S. star-and-shield design. There is little doubt that Ransom Williams was an accomplished horseman since he had his own horse brand and worked with horses for more than 30 years. Like most horsemen, he probably took pride in his horse gear, and the star-and-shield snaffle bit was the most ornate piece of horse tack that was found. He could have obtained a secondhand bridle or bit and been oblivious to the symbolism, but this seems unlikely. Rather, Ransom probably selected this bit intentionally because he was proud to display this patriotic symbol when riding his horse in public. The third artifact with U.S. symbolism is most intriguing. It is a commemorative spoon, manufactured to honor Captain Sigsbee and the battleship USS Maine that sank in Havana Harbor in February 1898. This was a critical event in the buildup to the Spanish-American War, and most adult American men would have been aware of this important national news. The item may indicate that Ransom Williams kept up with current political affairs and wanted to display his patriotism and support for the U.S. war effort. In addition, he was probably well aware that many African American soldiers fought and died in the Spanish-American War, and this may have been a source of pride for him as well. Ironically, Ransom purchased the commemorative spoon less than three years before he died. Participants in a Regional African-American Economic NetworkThe Williams family was typical of many American consumers in the last quarter of the nineteenth century, and their material remains denote their success in farming endeavors. As African Americans, however, their success was exceptional, given the restrictions imposed on their freedom and social interactions during the post-emancipation, Jim Crow era. Blacks in the post-war South cooperated with whites economically, but their relationships were seldom on the social level, at least not in public. Blacks attended segregated churches, went to segregated schools, and followed a strict set of rules for how they should behave and interact with whites on a day-to-day basis. Like the rest of the South, central Texas was a highly segregated and discriminatory society, and the Williams family had to deal with this reality. Within this context of mandated social segregation, African Americans not only congregated into their own communities, but they also sought to create their own businesses and economies. Whenever possible, black consumers tried to do business with black-owned enterprises; they would buy products manufactured by blacks or black-owned firms, and use the services provided by blacks. In addition, blacks also sought to do business with national and local companies that were friendly to the African American community, especially those firms that catered to black consumers through advertising. Two lines of evidence from the farmstead indicate the Williams family was indeed connected to a regional African American economic network and even consumers of African-American-made products. In both cases, the evidence involves interpreting artifacts from the farmstead in light of historical evidence. Archeologists found numerous stoneware sherds at the Williams farm that, looked quite similar to some of the stoneware made at the Wilson potteries near Seguin, Texas. These historic potteries—among the earliest African American-owned businesses in Texas—were operated by brothers Hiram and James Wilson, both former slaves of the Rev. John McKamey Wilson, who founded the first pottery-making enterprise there in 1857. Although we know very little about the distribution and marketing of their wares, the Wilson potteries operated for many decades, and their pots were widely distributed. It is reasonable to suggest that after 1865 the Wilson potteries would have distributed their wares to white-owned and black-owned retail stores throughout the central Texas region. To determine if the four reconstructed stoneware vessels from the farmstead were from the Wilson Pottery, a sourcing study (Neutron Activation Analysis) was conducted on the sherds to compare their chemical constituents to samples from the pottery and other sites. This involved a statistical analysis of 32 elements to define the chemical clusters. Based on findings from the analysis of 50 sherds, we can tentatively say that the four pots from the farmstead were made at one of the Wilson potteries. If correct, this interpretation is significant for African Diaspora studies because it denotes a specific type of consumer behavior among late-nineteenth-century freedmen, and it demonstrates that rural freedmen farmers in central Texas were participants in a larger regional economic network that involved black-owned businesses. Another line of evidence suggests the Williams family patronized businesses that marketed to the African-American community. Seven bottles found at the Williams farmstead bear the name of the Morley Brothers Drugstore or one of its products. The Morley Brothers started their business in downtown Austin in 1874, and they advertised regularly in African American newspapers in the 1890s. In conjunction with the Williams farmstead artifact analysis, University of Texas archeologist Nedra Lee reviewed five different African American newspapers published in Austin from 1868 to1907, looking for historical evidence of how the news media influenced the freedmen communities and the identities of black Texans. She recorded each paid advertisement that appeared in 135 issues. This data turned out to be quite useful for interpreting the artifacts recovered at the Williams farmstead. We discovered there was a strong correlation between many of the glass bottles that were found at the farm and several specific products that were advertised in the newspapers. Although members of the Williams family likely did not read advertisements for products in the Austin newspapers, they would have still been connected to the local African American economic network. They were linked to the larger freedmen community through church, their kids attending school, social events (such as Juneteenth celebrations), and through the local stores they would have patronized. All of these factors would have steered them toward doing business within their own community and informed them of the large economic sphere of black-owned and black-friendly businesses. The End of an Era:

|

|