The Williams family lived and worked their farm south of Austin for three decades in the late nineteenth century and into the first years of the twentieth century. As African American freedmen, their life was much different than that of people of European descent. One cannot fully understand the African American experience in Texas or the United States without knowing a little of the history of slavery, emancipation, reconstruction, and the great migration.

Slavery in Texas

Spain was a global political and economic power that grew wealthy on the African slave trade and the commodities produced by African captives in its New World colonies. Yet Spanish Texas (1690-1821), far-flung from the center of the Spanish empire, held little interest for the crown. Beginning in 1690, Spain established Catholic missions in Texas, and by the end of the eighteenth century, there were several towns. Still, the region’s total population was small, and Spanish Texas never developed an economy that relied heavily on enslaved labor. Thus, relatively few enslaved individuals resided in the frontier region of what is now Texas.

It wasn’t until the 1820s and Anglo-American settlement that the population of enslaved Africans and blacks began to rise in Texas. The key turning point proved to be American Stephen F. Austin’s colonization of southeast Texas. Austin inherited a Spanish empresarial grant from his father which would allow him to settle 300 families in Texas. Although Austin began to bring families in 1821, Mexico’s declaration of independence from Spain in that year threatened his plans. It took several years before Mexico recognized Austin’s grant, and before the end of the decade, he was able to grant 297 titles to Anglo-American settlers and their families. These families have come to be known as the “Old Three Hundred.”

Austin and the Old Three Hundred played a major role in paving the way for slavery in Texas. These settlers hailed from slave states such as Tennessee, Arkansas, and Louisiana, and a large number brought their enslaved laborers with them. They colonized a large swath of land along the lower Brazos and Colorado rivers that was ideal for planting. Austin implemented regulations in 1824 which included a set of codes that helped to solidify slavery in his colony. These included prohibitions against buying goods from slaves without the permission of their owners and rules governing slave punishment. The regulations served to reaffirm the rights of slaveowners over their human property.

Although the Mexican government attempted to curtail slavery in Texas, Anglos largely ignored their prohibitions. For example, in 1827 it became illegal to bring slaves into Texas; those newly arrived in the colony were required to be freed within 6 months. To get around the law, slaveowners had their enslaved blacks sign documents of indenture. Still, enslaved laborers remained a relatively small percentage of the Texas population as slaveowners were reluctant to migrate to a colony where slavery wasn’t fully protected by the law.

Following the Texas Revolution, slavery expanded rapidly on the heels of independence and the certainty that the institution had a major role to play in the new republic. The Texas Constitution of 1836 even forbade free blacks from living in the republic without permission from Congress. Thousands of blacks entered Texas, most of them likely arriving with slaveowners from the upper South. Numbering roughly 5,000 in 1836, there were over 27,000 slaves in Texas by 1845 as it entered statehood. As the population of Texas skyrocketed, so did the numbers of slaves, By 1847, Texas pegged its population at 142,009, an increase of 269% since 1836. During the same period, the population of slaves grew to 38,753, an increase of 675%.

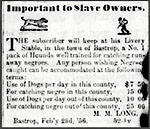

Following statehood, newspapers increasingly carried advertisements of slaves for sale and by the 1850s, the ports of Galveston and Houston had resident slave dealers holding auctions. The firm of McMurry and Winstead announced:

Negroes for Sale:

We have just arrived and permanently located in Galveston with a large lot of young and likely Virginia and North Carolina Negros which we will sell on reasonable terms. We have made arragements for fresh supplies during the season and will always have on hand a good assortment of field hands, house servants and mechanics. Persons wishing to buy Negros would do well to give us a call before purchasing elsewhere.

Ships, such as the S.S. Texas, plied the waters between Galveston and New Orleans carrying cargoes of cotton—and slaves. For such voyages, two separate manifests were required: one for products and materials, the other for human cargo. The slave manifest listed each individual’s name, sex, age, height, color, and owner. They were not passengers, however, but cargo, “held to service and labor.”

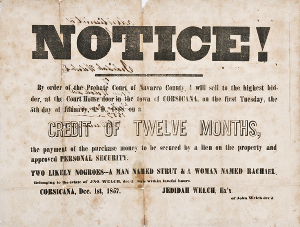

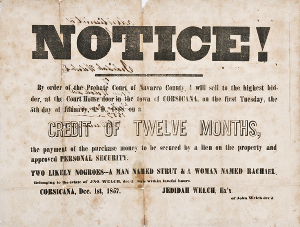

In small towns, slaves were sold, mortgaged, and even periodically hired out among farmers and planters. An 1857 notice advertised the sale of “two likely negroes—a man named Strut and a woman named Rachel” to be held at the courthouse door in Corsicana, Navarro County, Texas, to settle an estate.

Despite the fact that Texas was a slave state, however, most Texans did not own slaves. For example, just over 30 percent of household heads in 1850 owned slaves. The vast majority of them worked as field hands growing cotton and corn. On plantations with larger labor forces, slaveowners typically kept skilled tradesmen like blacksmiths and carpenters who could also be hired out. As with males, even though enslaved women and girls generally worked as fieldhands, wealthier planters used them as seamstresses, spinners, cooks, and nannies.

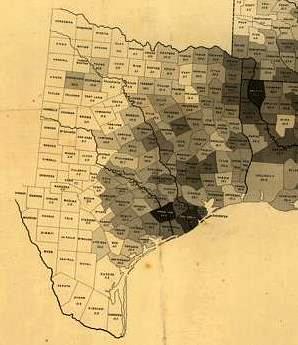

Although total numbers of slaves in Texas were low compared to some of the other slave states, the rate of increase from 1850 to 1860—and attendant impact on the Texas economy—was enormous. The decade saw a 214% growth in numbers of slaves in Texas, from 58,161 to 182,566. Production of cotton during the same period rose from a total of 60,000 bales to 400,000 bales. Plantations across the state were concentrated heavily in the most fertile bottomlands along the Trinity, Brazos, and Colorado Rivers, as well as lesser rivers and streams, a broad area characterized by historian Randolph Campbell as “Cotton Frontier.” He notes: “By 1860 King Cotton had the eastern two-fifths of Texas, excepting only the north central prairie area around Dallas and the plains south of the San Antonio River, firmly within his grasp."

In the last decades of U.S. slavery, well over half of the enslaved blacks in Texas were part of slaveholdings that consisted of 10 or more bondsmen. These slaveholdings represented about 1 in 4 slaveowners who together possessed over 60 percent of all Texas slaves. Even though the state’s slaveowners were in the minority numerically, they were able to translate their wealth and social standing into political power as a majority of the state’s political offices were held by slaveowners.

Emancipation

Although the Emancipation Proclamation was issued on January 1, 1863, nominally freeing slaves in Confederate states, the announcement had no effect in Texas until federal troops arrived in Galveston two and half years later. On June 19, 1865, General Gordon Granger read the Emancipation Proclamation, the first notice for many of the slaves in Texas that they were free. This date, celebrated as “Juneteenth,” is a major African-American holiday in Texas and in other regions of the U.S.

The news was a cause for celebration, but also raised new concerns. In 1865, more than 250,000 formerly enslaved African Americans in Texas faced the challenges and opportunities presented with their emancipation. What, for them, did freedom mean? By law, no one could own them again. Still, freedom did not mean equality with whites, and it did nothing to erase the legacy of nearly 300 years of slavery. Because of their former enslavement, the majority of African Americans were poor, knew no other work beyond planting, and few could read or write. Moreover, slavery was based on race, and the discrimination against blacks only intensified following the Civil War. Southerners, whether slaveowners or not, had fought to keep the institution in place and resented the fact that thousands of free blacks could now expect wages for their labor. Hostilities against African Americans in the form of physical violence, unfair treatment in the workplace, and segregationist attitudes sharply curtailed their prospects. Thus, they struggled to define the meaning of freedom in a racially antagonistic society and fought to gain a foothold within it.

The Years of Reconstruction

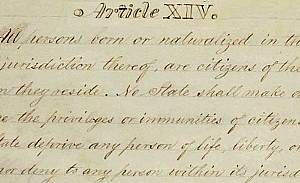

The era of Reconstruction refers to the years from 1865 to 1877, when the federal government politically restructured Southern states and attempted to address the challenges faced by freedmen within a racially hostile South. Terrorized by lynch mobs, the Ku Klux Klan, and Red Shirts, and lacking protection from authorities as well as redress for their grievances, African Americans were hard pressed to make any social or economic gains. Seeking to improve their living conditions, collect fair wages, and to achieve full citizenship rights, African Americans found obstacles at every turn. Although no longer enslaved, the vast majority had little choice but to remain on plantations and enter into tenant farming or sharecropping agreements with former slaveowners. It was common for sharecroppers to get trapped in a cycle of debt with landowners who took advantage of them. To many, the system of blacks laboring on white-owned farms in destitute conditions was a merely a new form of slavery.

As white Southerners worked against the interests of African Americans, agents with the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands conversely began the process of assisting whites and blacks displaced by the war. Created by Congress one month before the end of the Civil War, this agency soon became known as the Freedmen’s Bureau. African Americans across the South turned to the bureau for help as the former Confederate states instituted black codes in order to keep their former slaves subservient. The Texas black code of 1866 legalized oppressive labor and apprenticeship contracts, imposed harsh penalties for even minor infractions such as vagrancy, and created the convict leasing system. Thus, agents of the Freedmen’s Bureau were often involved with investigating labor contracts, including sharecropping agreements, and served as legal advocates for African American workers. They also played an important role in black education and helped to reunite families torn apart by slavery.

Although the Freedmen’s Bureau was established as a temporary agency with one year to carry out its mandate, it continued to operate until 1872. Southerners were determined to undermine the newly gained constitutional rights of blacks, however, and the bureau’s attempts to get blacks and whites to work together equitably largely failed. By 1877, Southern Democrats regained political power, and the last of the federal troops were withdrawn from the South. Reconstruction, which most historians agree was a dismal failure, effectively ended.

The Jim Crow Era

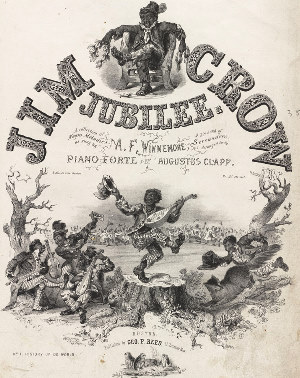

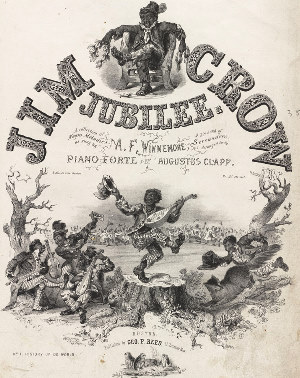

As soon as the Federal troops left, the white society across the South began to undo much of the social progress that African Americans had made. State, county, and local governments began to enact laws and establish policies to segregate blacks from whites in public places, schools and churches, on public transportation, and in employment. African Americans also were not allowed to take part in many social or political activities. These discriminatory practices became known as Jim Crow laws, derived from the name of a black character that first appeared in a song in 1828 and became a common black caricature in minstrel shows during nineteenth century.

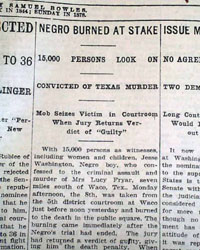

The threat of violence became a constant for many African Americans. Too easily, they could be accused of crimes, punished or executed without being given due process of law. Late nineteenth-century newspapers chronicled frequent lynchings and other unlawful acts against blacks. When a lynching occurred, it often was made into a public spectacle and widely publicized as a warning to blacks to follow the “rules” imposed by white society.

Successful black people were particularly vulnerable to the animosity of the white population.. A black preacher, John Smallwood, observed in 1911 that: “So long as negroes will drink common whisky, dance jigs, and make apes of themselves, the mass of white men in the Southern States applaud them as good fellows; but as soon as one becomes a bank president, a property owner, and a gentleman, he becomes offensive to society.”

The Great Migration

From the early 1900s and throughout the 1960s, five to six million African Americans migrated from Southern states to cities in the Midwest, West, and Northeast. This movement is referred to as the Great Migration, and by the end of it African Americans went from being a largely rural to an urban population. People left the South largely to escape racism and poverty and sought better-paying jobs in cities like Chicago and New York. It is estimated that between 700,000 to 1,000,000 people left the South during World War I alone, when the war disrupted European migration to the United States. Lacking foreign laborers, factories in the north readily hired African Americans in their place. Black migration was facilitated by the trans-regional railroad system which made travel over vast distances relatively fast and cheap.

In the early years, between 1900-1920, most African Americans left sharecropping and tenancy not for Northern destinations, but for urban Southern ones. Members of the Williams family were representative of this initial rural emigration. Following Ransom Williams’ death in 1901, Sarah Williams and her children left their farmstead near Manchaca and resettled in nearby Austin. For many African Americans, cities like Austin, Dallas, and New Orleans served as a temporary home before they attempted the more ambitious trek out of the South. |

Map of Texas, 1835, showing Austin's colony and other land grants in Texas as immigration into Texas from the United States increased. Compiled by Stephen F. Austin; published by H. S. Tanner, Philadelphia.  |

|

Following the Texas Revolution, slavery expanded rapidly on the heels of independence and the certainty that the institution had a major role to play in the new republic. Numbering roughly 5,000 in 1836, there were over 27,000 slaves in Texas by 1845 as it entered statehood.

|

Notice of sale of two slaves, "a man named Strut and a woman named Rachel," in Corsicana, Texas, Dec. 1, 1857, in probate settlement.

|

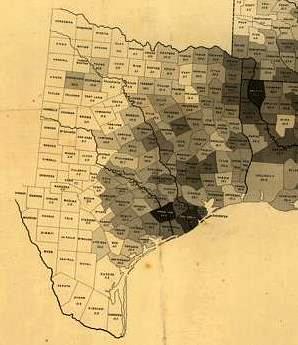

Map showing the distribution of slave population of the Southern states, compiled from census of 1860. Library of Congress.  |

Cargo Manifest of the S.S. Texas from the Port of Galveston to New Orleans, 1860. The steamship made weekly trips between the two cities. On one such trip, the S.S.Texas had two types of cargo: 140 bales of cotton and 28 slaves from New Braunfels, Texas near San Antonio. National Archives, Records of the U.S. Customs Service, 1745 - 1997.  |

Emancipation, by Thomas Nast. This depiction of emancipation at the end of the Civil War envisions the future of free blacks and contrasts it with various cruelties of the institution of slavery. Published by S. Bott, Philadelphia, 1865. American Memory: Library of Congress.  |

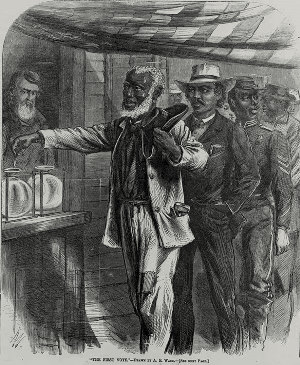

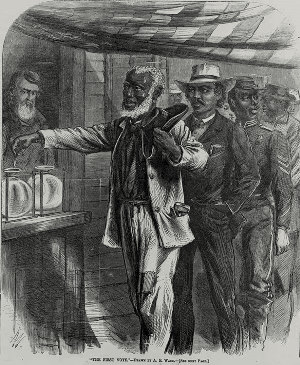

"The First Vote," by Alfred R. Waud, from Harper's Weekly, Nov. 16, 1867. Library of Congress.  |

| More than 250,000 formerly enslaved African Americans in Texas faced the challenges and opportunities presented with their emancipation in 1865. What, for them, did freedom mean? By law, no one could own them again. Still, freedom did not equate to equality with whites, and it did nothing to erase the legacy of nearly 300 years of slavery. |

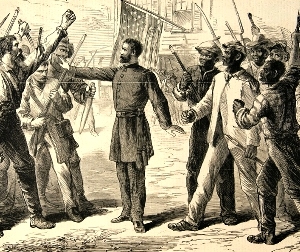

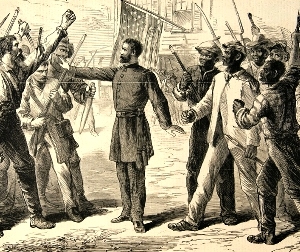

In this 1868 Harper's Weekly illustration, an officer representing the Freedman's Bureau holds off armed groups of white and black Americans. The bureau, charged with assisting freed slaves, enraged Southern whites who saw it as an extension of the army of occupation which envisioned a role for blacks they did not share. Wood carving by Alfred R. Waud, Library of Congress.  |

Visit of the Ku Klux Klan. This 1870s depiction of a Klansman pointing a rifle through the doorway at an African American family speaks to the terror that many blacks experienced across the South following emancipation. Klansmen also preyed upon white officials and even clergymen perceived to be sympathetic to black causes. Harper's Weekly, Feb. 24, 1872. Library of Congress.  |

Cover of an 1847 Boston musical production called Jim Crow Jubilee. The Jim Crow character originated in the minstrel shows in which white actors dressed as blacks and mimicked them on stage. The caricatures of Jim Crow became increasingly more derogatory through time, and the term was eventually applied to all of the various laws of racial segregation that sprang up across the South after Federal Reconstruction ended in 1877.  |

|