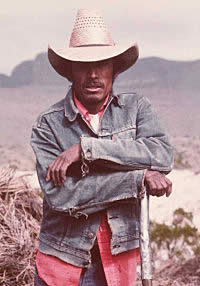

Leaning on his pitchfork, a

worker takes a break from pitching weed into the

vat. While early candelilleros wore khaki clothing,

tire-tread sandals and a handmade hat from Mexico,

today's workers wear blue jeans, imitation leather

shoes and a western hat or baseball cap. Photo

by Raymond Skiles. Click to see full image.

|

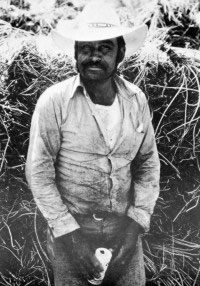

A cerero and his burro relax

for a moment. Some of the workers are family men

who travel back to their villages from time to

time to see their families and get supplies. Photo

by Curtis Tunnell.

|

|

If you are wanting to buy a burro it is always

worth 100 dollars, and if you are wanting to sell

one it is always worth 25 dollars.

|

A wax maker's meal, consisting

of black coffee, beans, and tortillas. At times,

the workers supplement their diet with wild game

and plants, such as hearts of desert lechuguilla

or sotol, which they slow-bake in hot ashes. Photo

by Curtis Tunnell.

|

A bag handmade from cordage

twisted from fibers from the desert lechuguilla

plant. Photo by Cutrtis Tunnell.

|

|

I was walking with a wax collector one time

when the candelilla load began to shift on the

burro. The man stepped over to a torre yucca and

stripped off some fibers with his fingernail and

twisted them into a crude cord and tied the candelilla

load to the packsaddle more securely.

|

Handmade sandals with soles

made of tire treads. Modern wax makers tend to

wear factory-made shoes. Photo by Curtis Tunnell.

|

|

Wax Makers: Conditions and Wages

Wax makers are called cereros or

candelilleros or occasionally paileros

and are always men. There is a conspicuous absence of

women in the camps. The occupation of wax maker is one

that many men along the border have practiced at one

time or another, and a few men work at the wax vats

for years.

All wax makers come from Mexico. You couldn't

get people in this country to make wax if it was worth

five dollars per pound. You can't just hire anyone to

make wax, they need to have had experience. It is very

hard work and relatively few men can do it well. The

men have to have tough hands and a strong back to pull

candelilla. They never use gloves and you can tell by

looking at their hands if a man has worked with wax

a long time. According to Davis Adams in a 1980 interview,

experienced men can get more wax from each ton of weed

and get more wax with less acid.

Some of the cereros are family men who

travel back to their villages—Las Norias, Boquillas,

Santa Elena, El Mulato—periodically to visit their

families, attend mass, and get supplies. Others are

young men who are wanting to learn a trade, earn sufficient

money to go to a city like Ojinaga or Juarez, or, more

likely, head north as illegal aliens. A few are drifters

or men outside the law and are hostile toward strangers

with cameras or hide in the rocks to avoid such contacts.

Generally cereros work eight to ten hours

per day and six days per week. Sometimes the men will

work for 20 or 30 days straight and then quit and go

to nearby towns "to see the girls and get alcohol."

They also like to observe all manner of religious and

political holidays. Some men may go well down into Mexico

to visit family or attend weddings. Their usual mode

of travel is by burro or "they just walk."

A good wax maker can gather the plants

for, and extract about 1,000 pounds of wax per month

if he works at it. One man can make wax by himself,

doing everything from gathering the plants to the final

boiling and bagging, but usually at least two men work

together. Men of the same family (for example, a man

and his sons or several brothers) often work together

on a crew.' When the price is right the men produce

wax the year round; however, slightly more wax is produced

in winter than in summer.

The men are paid a little more if they

provide their own burros, but a foreman or rancher always

has extra burros on hand. When asked the price of a

burro, one informant said: "If you are wanting

to buy a burro it is always worth $100, and if you are

wanting to sell one it is always worth $25." He

estimated a good average price in 1980 to be about $50.

Adams said wax makers on his ranch will

work hard until they have made $200 or $300 in a month,

then they begin to slack off. If they worked hard all

month they could make as much as $600, but they don't

seem interested in making as much money as possible

each month. He believes that, generally, the standard

of living of the wax makers is much better than it used

to be, and that "some day if Mexico becomes sufficiently

affluent, no one will want to produce candelilla wax.,"

Adams said. "You gotta have a commissary if you're

going to produce wax." He said he always sells

groceries to the men because they have no other place

to get them. "You can't just provide them with

food because if you do they will use a pound of coffee

per day, but when they have to buy it themselves a pound

of coffee will last them for a week."

The most common items which he sells to

the men include coffee, beans, potatoes, flour, black

pepper, salt, canned tomatoes, vermicelli, lard, roll-your-own

tobacco, onions, and chile peppers. He said it is rare

for the men to have meat, but occasionally they may

have a chicken or a goat if those can be acquired cheaply

from a nearby homestead. They also kill javelina hogs

on the ranch but are not permitted to kill deer. Traps

are used by the men, since they are not permitted to

have guns on the ranch. Adams said that, since he also

forbids the wax makers to have liquor, things are fairly

quiet on the ranch.

Adaptation and Improvisation

Cereros take little in the way of material

possessions with them to the camp. An iron wax vat with

grate, burros and packsaddles, machetes, burlap bags,

rope, jars of acid, a few cooking pots, staple food,

and a change of clothes make up the usual inventory.

The men are masters at improvisation, adaptation, and

"living off the land." This is perhaps best

illustrated by the shelters that they find or fabricate.

The cereros' use of the candelilla is especially noteworthy,

for not only does the plant produce the wax and provide

fuel for the vats, the wax makers also use it for their

beds and as thatching for various types of shelters.

The types of shelters and their methods of construction

are discussed in the section on camps below.

Candelilleros fabricate many of the tools

they use for work, the implements they use in cooking,

and even the clothing they wear. Pack saddles often

are made from pieces of driftwood held together with

rope, pegs, and salvaged nails. An acid dipper consists

of a small can or jar tied in the fork of a stick. A

wax skimmer is made from a flattened tin can perforated

with a nail and attached to a handle with wire and nails.

Pitchforks for stoking candelilla into the fire are

carved from forked mesquite branches. If no wheelbarrow

is available, candelilla is stacked on two parallel

poles and carried between two men.

A griddle for tortillas is made by cutting

the flat end from a steel drum. Wooden pegs are cut

and driven into shelter walls for hanging clothing and

food. A hanging wire serves to keep food out of the

reach of rats. Sandals are fabricated from the tread

of old tires, and shoes may be repaired and reused as

long as bent nails will sustain them. Leggings of raw

goat skins are sometimes used to reduce the painful

wounds inflicted by lechuguilla and Spanish daggers

on the gathering slopes. Plastic bleach bottles lost

by fishermen are the usual water canteens seen around

camps and carried on burros.

One informant, Bob Burleson, described an example of

spontaneous inventiveness:

I was walking with a wax collector

one time when the candelilla load began to shift on

the burro. The man stepped over to a torre yucca and

stripped off some fibers with his fingernail and twisted

them into a crude cord and tied the candelilla load

to the packsaddle more securely.

Sotol and lechuguilla are readily available

sources of good fibers for twisting into twine and rope,

which are used in the harvesting of the weed, fabrication

of bags and shelters, repair of tools and clothing,

and for many other purposes. We have seen piles of leaves

and quids from both species where hungry cereros have

baked the plants in hot ashes at the front of fire pits

and feasted on the nourishing hearts. Our field party

baked hearts of both plants in an earth oven for 20

hours and found them to be soft, quite palatable, and

almost tasty.

For the most part the wax makers have

been friendly and cooperative with our field crews,

permitting us freely to take photographs, ask numerous

questions in broken Spanish, wander around camp, draw

maps, and pet burros. An occasional small mordida

of cold beer or money improved communications and helped

compensate the workers for time lost in conversation.

The Camps

|

|

You couldn't get people in this country to

make wax if it was worth five dollars per pound.

|

The weathered hands of a wax

maker, breaking up chunks of raw cerote with a

stone. Candelilleros need tough hands and a strong

back for the job. Photo by Raymond Skiles.

|

Resting against an enormous

mound of weed, candelilleros pose for photographer

Curtis Tunnell. Click to see full image.

|

|

Cereros take little in the way of material

possessions with them to the camp. They are masters

at improvisation, adaptation, and "living

off the land."

|

Camp necessities. A griddle

for cooking tortillas is a must-have item in the

camps. This one was made from the end of a steel

drum. A wooden tortilla roller and cut cane cigarettes

are in foreground. Drawing by Sharon Roos, THC.

|

Fibers from the spikey leaves

of desert plants such as lechuguilla (shown) and

yucca can be quickly stripped and made into cording

for rope or knotted into carrying bags. Photo

from ANRA-NPS Archives at TARL.

|

Two well-used wax skimmers

handmade from tin cans. Photo by Curtis Tunnell.

|

A hard-working cerero enjoying

a small "mordida" of cold beer offered as a small

token of gratitude by archeologists who interviewed

them and photographed their work. Photo by Curtis

Tunnell.

|

|

|

Abandoned wax camps are familiar sites

along the Rio Grande. Many are reused after the candelilla

stands have grown back in the area. Note the steel wax-boiling

vat (overturned, at left) and the sagging remains of a ramada,

or shelter, on right. This camp is in Santa Elena Canyon.

Photo by JoAnn Pospisil.

|

A worker continues to boil

wax despite Rio Grande flood waters within inches

of entering the firebox. The processing stations

are typically located immediately beside the river

to have easy access to water; camp and sleeping

areas are set further back. Photo by Raymond Skiles,

Boquillas Canyon, 2002. Click to see full image.

|

A seasoned wax maker loads a vat with weed. In some camps, there is often an older, master wax maker who is nominally in charge of operations. Photo by Raymond Skiles. |

| |

| |

| |

|

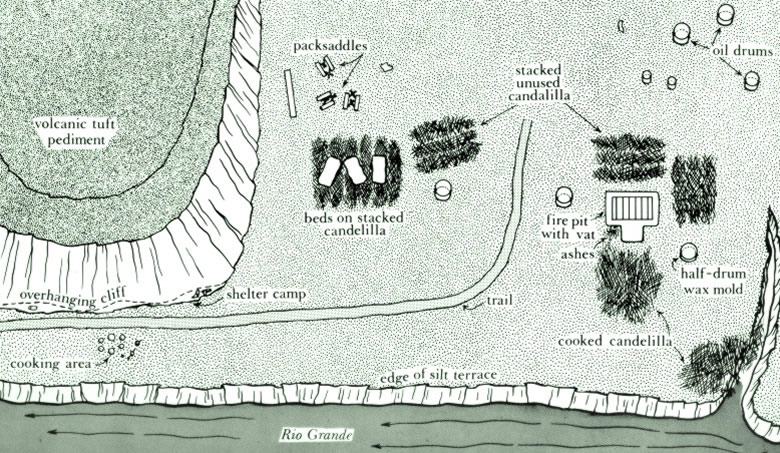

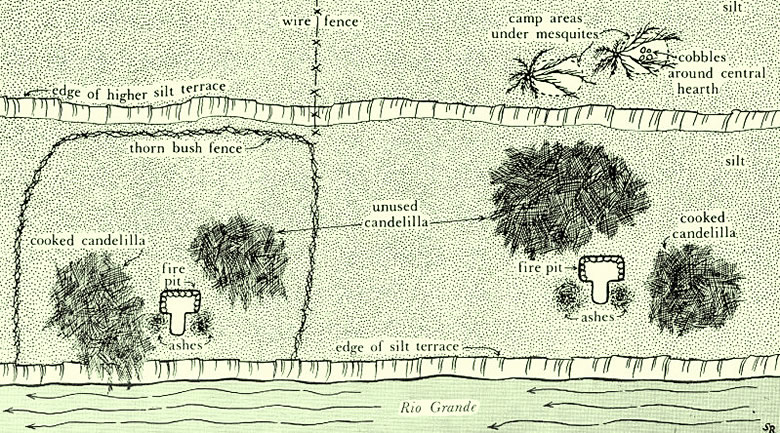

Location and Features

Rarely, a wax operation may be set up

sufficiently near a settlement that the men can commute

from their homes to the production area, but most such

locations were exhausted long ago. By far the most common

pattern is for several men, three or four to eight or

ten, to take their vats and donkeys into a remote can-yon

area where candelilla is abundant and establish a camp,

which they may use continuously for months and intermittently

for years.

A few camps may be found near springs,

tinajas (potholes), or windmills, but the majority,

even those in out-of-the-way places in the canyons,

are located near the river. The camps occur on both

sides of the Rio Grande and seem to be situated according

to convenience with no consideration of the international

boundary. The vats usually are placed immediately beside

the river on the first terrace, about 6 or 7 feet above

normal river flow and 10 to 12 feet back from the terrace

edge. Living areas may be from 30 to 100 feet farther

back on the same level but are more often on the edge

of the second silt terrace. The area of the camps varies

from about a quarter acre to as much as two acres, with

most of the area devoted to stockpiles of candelilla

awaiting processing and spent weed drying for fuel.

The most prominent features in the camps

include vats and firepits, deeply worn trails, piles

of ashes, sleeping shelters, candelilla stock-piles,

yerba seca (cooked candelilla) piles, sun-shades

or ramadas of various types, brush fences, and

burned areas in brush and cane along the river. The

most obvious activity area in a camp is the area where

the weed is processed. The living area where the men

sleep and cook is also clearly delimited in most camps.

Occasionally there may be an area where the burros are

maintained. Trash seems to be scattered randomly about

rather than deposited in a systematic way.

Work Organization

There are various types of organization

in the wax camps. Some camps are composed of several

individuals who gather weed for themselves and take

a "turn" at the wax pit when they have stockpiled

sufficient candelilla. Other camps, especially those

on ejidos, consist of a group of men working

in common and sharing in the profits of the operation.

A few camps belong to one man, a rancher or jefe,

who pays wages or a commission on the wax to the workers.

Adams said there were from five to seven camps producing

wax on his ranch in 1980, and these are operated according

to a modified commission plan. He has a foreman who

buys wax from the camps and then sells it to Adams,

and the man makes about 10 cents per pound for the transaction,

Adams finds it necessary to buy the wax by the sack

even though it is produced on his land, because if he

paid the candelilleros to produce it, he would not get

as much for his money. Buying wax produced from his

own weed costs the same per pound as wax brought from

Mexico.

Job assignments in the camps vary. In

some, men seem to have particular jobs—stoking

the fire, carrying water, skimming the vat, breaking

wax blocks, bagging cerote—and the jobs have different

status within the group. In other camps chaos seems

to reign, with different men doing different jobs at

different times and some obviously doing more than their

fair share. There often is one older man, the master

wax maker, who is nominally in charge.

Shelters

|

|

The most prominent features in the camps include

vats and firepits, deeply worn trails, piles of

ashes, sleeping shelters, candelilla stock-piles,

yerba seca (cooked candelilla) piles, sun-shades

of various types, brush fences, and burned areas

in brush and cane along the river.

|

A camp beneath the trees with a makeshift storage platform. Note the plastic carrying bag hanging in the tree at left, a more common sight now in wax camps. Photo by Curtis Tunnell. |

Squatting in front of the boiling vat, a worker skims waxy foam off the top. Some camps have assigned tasks for workers, and the jobs have a different status within the group. Photo by Curtis Tunnell. |

| |

| |

|

|

Wax camp above Mariscal Canyon. Note cerrero's beds "under the stars" on stacks of candelilla at center and shelters in overhanging cliffs at left. Drawing by Sharon Roos, THC. |

|

In pleasant weather the wax makers usually

prepare meals on open hearths and sleep on top

of candelilla piles under star-filled skies.

|

A small cavity in a limestone

cliff has been turned into a compact shelter for

a wax maker. Front view (A) and overhead view

(B). Drawing by Sharon Roos, THC.

|

|

In pleasant weather the wax makers usually

prepare meals on open hearths and sleep on top of candelilla

piles under star-filled skies. However, shelters are

always provided in the camps for those nights when rain

storms rumble through the canyons or cold north winds

bring chill and frost.

Rockshelters are the quickest, easiest,

and most durable type of shelter available in the desert,

and the cereros never miss an opportunity to use them.

In some areas, small cavities and crevices in limestone

serve as individual living units, which may be furnished

with candelilla and burlap-bag beds, pegs, and a rat

wire for protection of food. These shelters serve well

in the most inclement weather. More commonly, overhanging

cliffs provide partial shelter for camps and storage

of possessions.

Simple to fabricate and reasonably effective

shelters are prepared under convenient mesquite trees.

Branches are chopped from the underside of two or three

large overhanging branches, and the shelters are thoroughly

thatched with candelilla and cardboard when available.

A candelilla bed and cobble-lined hearth complete the

living unit, which is effective in a rain but gives

little shelter from cold wind.

|

An ocotillo plant in fiery

bloom looms over a stand of candelilla. Limbs

of the ocotillo are used as poles in the waxmakers'

camp shelters. Photo by JoAnn Pospisil.

|

|

|

A wax camp where workers constructed mesquite shelters in Boquillas Canyon. Note fence made of thorn bushes at left, encircling the processing area. Drawing by Sharon Roos, THC. |

A "house" made of plants. This

typical wax maker's shelter, shaped like a pup

tent, is made of poles from the desert ocotillo

plant, is tied with cording of lechuguilla fibers,

and is thatched with candelilla. Front view and

side view. Drawing by Sharon Roos, THC.

|

A rusted steel wax vat is lodged

in the sand, after having been washed away by

a flood. River camps always run the risk of losing

vats during floods. Photo by Raymond Skiles.

|

Waiting for the wax to boil.

When not actively engaged in processing, waxmakers

spend much of their time standing or squatting.

Photo by JoAnn Pospisil.

|

|

At sites where high silt terraces face

the wax-producing ground, substantial dugout shelters

may be prepared. These have well-smoothed walls with

niches and pegs for storage and unlimited potential

for graffiti. The roofs are made with wooden support

poles and vigas thatched with thick layers of candelilla

interspersed with cardboard and rags. Candelilla beds

and cobble-lined hearths are on the floor. These dugouts

provide adequate shelter for most weather and may survive

for years in a desert environment.

Another type of fabricated shelter is

about the size and shape of a pup tent. This type is

made from a framework of wooden and ocotillo poles tied

together with lechuguilla fibers and thatched with candelilla.

A candelilla bed and plastic water bottle constitute

the furnishings. Hearths are not compatible with these

shelters, which provide only moderate protection from

rain and cold.

Wax Vats

Like the shelters improvised by the workers,

the equipment used in making wax varies from camp to

camp and according to circumstance. A large wax vat

(called a paila or occasionally caldera

by the cereros) may be made from half a steel boiler

cut lengthwise or fabricated from sheet steel in a welding

shop in one of the larger cities. In some camps the

vats are provided by the wax refiner and do not belong

to the cereros who use them. The vats vary in size and

shape but may be about 6 feet long, 3 feet wide, and

3 feet in depth. A heavy steel grate is attached at

either end by loop hinges and, after much stomping to

submerge the weed, a lever clamps the grate at the center

to hold the load in place until the wax is boiled off.

The vats and grates can be used for years, although

they frequently need patching or small repairs.

A small wax vat made from half an oil

drum cut lengthwise was seen tied between two wooden

poles and carried by two burros. It was designed for

easy transport into a remote niche where a tinaja of

rainwater would support a brief rendering operation.

A grate of hardwood sticks was used to submerge the

weed in this small vat.

Modern Conveniences

Certain categories of things, which we

who are accustomed to a more affluent existence might

expect to find in wax camps, have never been observed

there. Trucks, although used to haul weed to some of

the early factories, are not in evidence. We have never

seen a motor vehicle, or remains of one, in camps along

the river. Devices for marking the passage of time such

as radios, calendars, clocks, and watches have not been

recorded there. Basic tools such as axes, hammers, and

saws are apparently replaced by machetes and hammerstones.

Lighting devices such as flashlights, candles, lanterns,

and lamps have never been seen in the camps; moonlight

and a campfire suffice at night. The convenience of

boats, mattresses, and even gloves cannot be afforded

by the cereros; nor can eye glasses, finger rings, dishes,

and flatware. For those who live standing up and working

or sleeping on the ground, there is no need for chairs

and tables. Common domestic animals such as dogs, cats,

and chickens have not been observed. The sharp eye of

a master wax maker judges the weight of bags of wax

in lieu of scales. Even such inexpensive conveniences

as books, paper, pencils, and soap are apparently beyond

the means of or simply not desired by cereros.

|

Fabric or blankets are often

draped over the shelters to provide another layer

of insulation. Drawing by Sharon Roos, THC.

|

|

For those who live standing up and working

or sleeping on the ground, there is no need for

chairs and tables.

|

|

|

|