Context and Classification

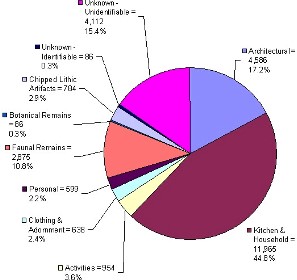

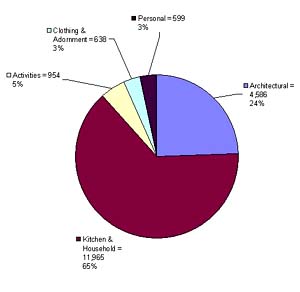

The artifact assemblage from the Williams farmstead is amazingly pristine from an archeological perspective for several reasons. The site was occupied for a relatively short period of time, about three decades, and the abandonment by the Williams family was fairly rapid in the first decade of the twentieth century. It also appears that the site experienced minimal disturbances after its abandonment. This unique combination of factors means that the entire artifact assemblage has an excellent archeological context, and its association with the Williams family is very strong. Among the thousands of artifacts, there are only a few that post-date the Williams occupation, but even these can be easily explained. For example, fragments of two glass bottles came from wine bottles manufactured after 1913, but these were all concentrated along one of the rock walls where someone was using them for firearms target practice after the Williamses had moved off the property. Another out of place artifact is a 1941 coin that was probably dropped by someone who visited. Even though the Williams family had moved off the property by 1905, they continued to farm the land or lease out the property, so someone was still coming to the old homestead. This type of contextually discrete assemblage can provide a wealth of information about the daily lives they experienced on the family farm. But the artifacts cannot speak for themselves and will not reveal their stories without some coaxing. In order to interpret the material remains, archeologists must identify, classify, and study the artifacts in many different ways. Classification by FunctionThe classification scheme chosen by PAI archeologists for the Williams farmstead analysis is essentially a modified version of the widely used functional classification system developed by historical archeologist Stanley South in the 1970s. The Williams farmstead classification scheme is presented in its entirety to show the comprehensive scope of the entire collection. This scheme employs ten main groups, with five key functional categories: Architectural, Kitchen and Household, Activities, Clothing and Adornment, and Personal. Within each major category, artifacts are further classified in subgroups and then specific artifact types. However, any classification scheme used to analyze material culture has certain strengths and weaknesses. This type of classification system is based on the original intended function for which each item was manufactured, and one of its strengths is that most items were indeed used for their originally intended purposes. The scheme does allow for items to have multifunctional uses, such as a pocketknife that had an unlimited range of potential uses. How it was actually used depended upon who owned it, and in this classification scheme pocketknives are classified as personal items without reference to the many ways they were probably used. When this classification system is employed in its strictest form, however, it does not adequately address the reuse of objects, which was and still is a common human behavior, or complex contexts where items were used in unusual ways. Any object will have a primary function, which is its original intended function, but it may also have many secondary functions, reflecting various ways in which items were recycled and reused. It is also acknowledged that many objects found on a farm may never have been used for their primary function and only been used in various secondary functions. A few examples will illustrate how complex it is to understand the primary and secondary functions of many items, and to show how their contexts or attributes can sometimes reveal their functions. A steel axe head was found at the farm, but its butt end was split open and battered from heavy use. Its primary function was as an axe, but its secondary function was its use as a wedge for splitting wood. Once it broke, it was considered useless and discarded into the trash midden. A long section of twisted metal rod, threaded on one end, was originally manufactured as a lightning rod, a safety device that could be installed on a house or barn. But only one section of lightning rod was recovered, and we found no clips to attach rods to a structure. This suggests that the lightning rod section was probably salvaged elsewhere and brought to the farm to be used in other ways, such as a pry-bar or a tether stake for securing an animal. A carbon rod from a dry-cell battery has a specific primary function to generate a direct electrical current, but the two specimens found at the Williams farmstead had their ends sharpened. We don’t know if the Williamses had some device that used a dry cell battery, perhaps a flashlight such as the “Electric Search Light” advertised with the dry-cell batteries in the 1902 Sears, Roebuck & Company catalog. In any case, we surmised that the battery carbon rods were sharpened to function as writing implements. Rules, Exceptions, and UnknowablesThe pie graph at right shows the relative frequencies of the functional classification groups of artifacts recovered from the Williams farmstead. The numbers of specimens in these groups vary widely, from 86 items in the Botanical and the Unknown-Unidentifiable groups to 11,965 items in the Kitchen and Household group. This graph also illustrates an important point—not all of the classification groupings are equally important for interpretive purposes. The most important groups for analyzing the historic artifacts are the five main functional groups—Architectural, Kitchen and Household, Activities, Clothing and Adornment, and Personal. Collectively, these groups comprise 70.2 percent of the total artifact assemblage and include all of the man-made artifacts that are most useful for interpreting the historic activities and behaviors that created the site. Two points are worth noting about these groups. First, to be consistent in the classification of thousands of artifacts, a set of rules was established to govern which items belonged in which functional groups. Second, there were exceptions to these rules. There were quite a few cases where an artifact was classified into a particular group based on its archeological context rather than its simplest identification based on its primary function. The faunal and botanical remains are not artifacts per se. These groups contain the animal bones and plant fragments that survived, and many of the specimens were indeed modified by people. Most of the plant remains are charred, and whether they were burned intentionally or accidentally, it was the burning that enabled them to survive. Some of the plants are charred woods used as fuel, while others are charred remains of foods that were consumed by the Williamses. Similarly, butchering marks and spiral fractures on many animal bones indicate that certain species were being killed and eaten, while some other bones only represent critters that lived around the farmstead and died of natural causes. The animal and plant remains are important evidence, indeed, but these groups combined only represent 11 percent of the recovered materials. Of the categories shown in the chart at top, three are excluded from further consideration in this online exhibit because they are really not that important for interpretive purposes. A small handful of items (n=86) are classified as Unknown-Possibly identifiable; these are mostly fragmentary specimens that have not been identified but perhaps can be in the future. More than 4,000 specimens are in the Unknown-Unidentifiable group, and these are dominated by small rusted pieces of iron. These are too corroded and too fragmentary to ever be identified, and they have little or no interpretive value. The last group is the chipped lithic artifacts, and it includes 784 specimens. These are mainly chert flakes and some core and tool fragments that were found in the excavation units but were not deposited or used by the Williams family. These chipped stone items are associated with a large, low-density prehistoric lithic scatter that covers most of the old farmstead. These artifacts provide evidence that Native Americans once used the land, but this whole category is not important for understanding the Williams farmstead. Having said this, there is one notable exception in the lithic category. A prehistoric dart point was found in the chimney firebox, and its context clearly indicates that it was picked up and placed there by someone who built the chimney. As such, this dart point represents an unusual historic activity, and rather than being lumped in with the unassociated lithics it was classified as a collectible in the Personal artifact group. A fragmentary arrow point also was found in the yard, and we will never know if its occurrence was fortuitous or if it was picked up and brought there by one of the Williams children. Of the total assemblage, 18,742 artifacts are classified into the five main functional groups, and these are the specimens of prime interest for interpreting the daily activities and rural life on the Williams family farm. But since these numbers can be misleading, a few words of explanation are needed here. First, whenever possible, each artifact was classified into one of the functional groups whether it was whole or only a fragment. For example, a nail fragment gets counted as one artifact just as a whole nail would be. One artifact might be a complete dinner fork, while another might be a single tine off of a fork. An entire cast iron cooking stove might be represented by only a leg section and fragments of its body and burner plates. This problem is unavoidable, however, since most artifacts that end up in a historic archeological site are actually fragments of much larger items. It is easy to see how the specimen numbers can become quite large depending on how objects were broken and dispersed within the site. This is particularly true of fragile items like ceramic vessels and glass bottles. With one glance at the artifact graph (above right), the Kitchen and Household group stands out because it contains many more artifacts that the other functional groups. This impression is misleading because the large number of glass fragments and ceramic sherds skew the data. In a nutshell, the Kitchen and Household group contains more fragments of fragile items than do all the other categories. In the rest of this exhibit section, it would be impossible to describe every type of artifact that was found due to the sheer size of the collection. For this reason, only selected groupings of artifacts are illustrated and discussed as being most representative of each of the five functional categories. |

|