House Complex

Click on any feature to explore |

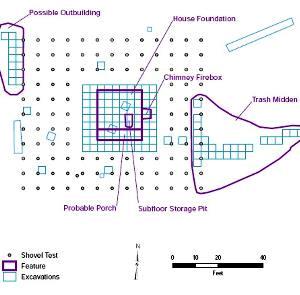

The Williams family lived on their small farm in southern Travis County for over three decades, from ca. 1871 until 1905. When archeologists visited the site more than 100 years later, the ruins of the house were still easily recognizable. Large foundation stones delineated the area where the old farmhouse once stood, and a pile of limestone rocks from the collapsed chimney covered the lower intact portion of the firebox. A little looking around revealed the unmistakable archeological signature of the household trash dump near the house and the level area that was once the yard. Because features and artifacts were most concentrated in and around the house, this area became the focus of the intensive archeological investigations. Excavations in the house area had two main goals: (1) to locate, document, and interpret the archeological features that make up the house complex; and (2) to gather a large sample of material remains once owned and used by the Williams family. The excavations concentrated on defining the footprint of the farmhouse, identifying the immediate yard area and household trash dump (midden), and obtaining material remains from all these areas. A probable outbuilding location was also identified and investigated. Archeological excavations were initiated with the digging of test pit units in the house complex area, and included three units dug in 2003 by archeologists from the Archeological and Cultural Sciences Group, Inc., and those subsequently dug by Prewitt and Associates’ archeologists during the 2008–2009 testing phase. The archeological testing yielded many artifacts dating to the late nineteenth century and demonstrated that the site had intact features and cultural deposits. At this point, TxDOT and THC archeologists agreed the site was significant and warranted extensive data recovery excavation. During the data recovery phase in 2009, digging was done in contiguous 1x1-m excavation units. When all of these are combined, the total number of 1x1-m units excavated in the house complex was 138. In addition, more than 100 systematic shovel tests were excavated at 2-m intervals around the 10x9-m house block. The artifact recovery from the 103 shovel tests (excluding the two previously excavated shovel tests) helped define the immediate yard area in close proximity to the house. The shovel test recovery data were then mathematically converted to “number of artifacts per square meter” for each test so the data could be compared directly to the artifact frequency for the 1x1-m units in the house block. This information was useful in the spatial analysis of the house area. The house complex was divided into “analytical units” that served as groupings for the intra-site comparisons and spatial analyses. The analysis units defined are as follows:

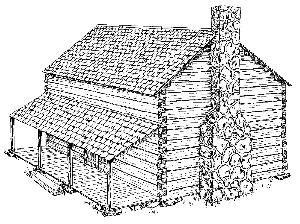

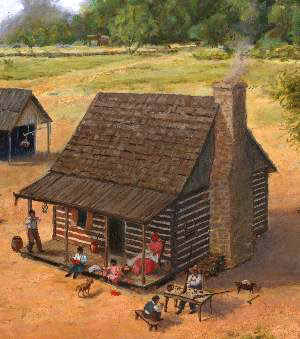

Cabin ReconstructionBased on findings at the house complex, we attempted to find analogs to help us understand how the structure might have looked. Historical circumstances and various types of archeological evidence suggest that the house at the Williams farmstead was a log cabin, and it might have looked quite similar to this reconstruction drawing of a log cabin at the Jones Farmstead (41DN250) in Denton County of north Texas. This drawing is modified from the original sketch (an attached lean-to was removed and the image was flipped) by Tammie Green in the 1996 publication called Historic Archaeology of the Johnson (41DN248) and Jones (41DN250) Farmsteads in the Ray Roberts Lake Area: 1850–1950, edited by Susan Lebo. Ransom built his house in the early 1870s, before the railroad came to Manchaca and before there were good roads nearby, so the farm was still in the relatively undeveloped countryside. This means that cut lumber, while available, would have been quite expensive to purchase and transport. A log cabin made perfect sense because oak and cedar trees were abundant on the Williams property, and some of them needed to be cut down to clear land for cultivation. It would have been very efficient for Ransom to clear the land and use the trees to build his log house. Further, a relatively small number of nails was found at the house site. Assuming that the farmhouse deteriorated in place and that there was no significant scavenging of wood and nails, the low number of nails suggests the house was a log cabin rather than a frame structure. Building a log cabin was a common practice for pioneer settlers in central Texas. Ransom Williams’ next door neighbor, Daniel Labenski, bought his land in 1871 and built a log cabin. The Labenski family later lived in a large wooden frame house, but as was often the case, their first house was a log cabin. Labenski family oral histories also have confirmed that the structure on the Williams farm also was a log cabin. In a 2003 interview with a family member, Daniel Labenski's daughter, Cordelia Labenski Dunahoo, recalled that "there used to be a log cabin on the property next to theirs that was owned by a black man called Rance." A historic study of early communities in the Onion Creek area of northern Hays County by Wayne Roberson reveals that many early settlers there built log cabins when they first arrived. A Swept YardAlthough it was less intensively investigated than the house footprint or trash midden, the immediate yard area around the Williams house proved to be an important component of the farmstead. After comparing the artifact recovery rates across the house complex, we discovered that the yard area had an extremely low artifact density and yielded an abundance of small and fragmentary items. To explain this phenomenon, we proposed that the Williams family maintained a swept-earth yard, keeping it devoid of vegetation and regularly sweeping it to remove debris. This practice, common on plantations in the southern United States, can be traced back to Africa and the Carribean. In addition to practical reasons, there are numerous folk traditions associated with yard sweeping (see the Transitions section of this exhibit for more detail).

|

|