Editor's Note: Cabeza de Vaca´s accounts of life among the native peoples of Texas and Mexico in the early 1500s have long piqued the imagination and curiosity of scholars and lovers of history. Much attention has been directed to fleshing out details of the explorer´s life and trying to pinpoint the route he and his companions traveled from the Gulf shores through south Texas and deep into Mexico. In this multi-section essay, anthropologist and archeologist Alston Thoms focuses on what the accounts tell us about native peoples and, in particular, about the various foods they hunted, dug, and plucked from often harsh landscapes. Thoms´ first-hand experiments with native plants and ancient cooking techniques and his familiarity with the traditional foodways of later peoples help illuminate Cabeza de Vaca´s brief and often enigmatic descriptions of the foods that were eaten, and the measures taken in order to survive. |

|

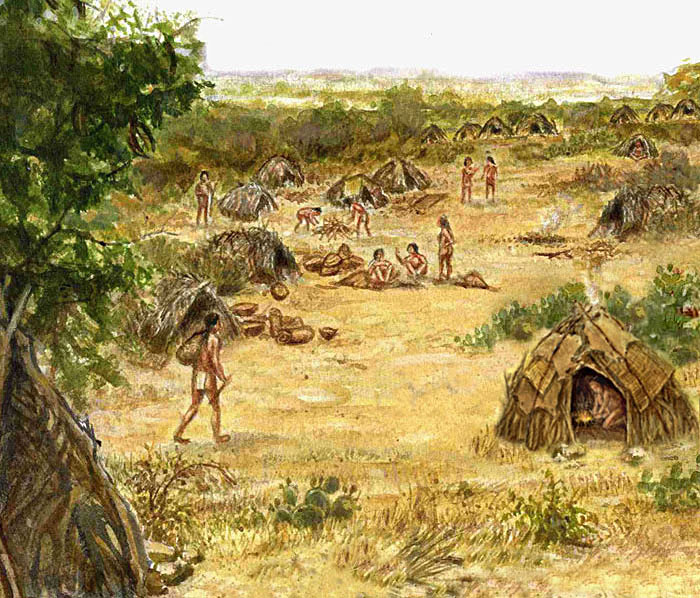

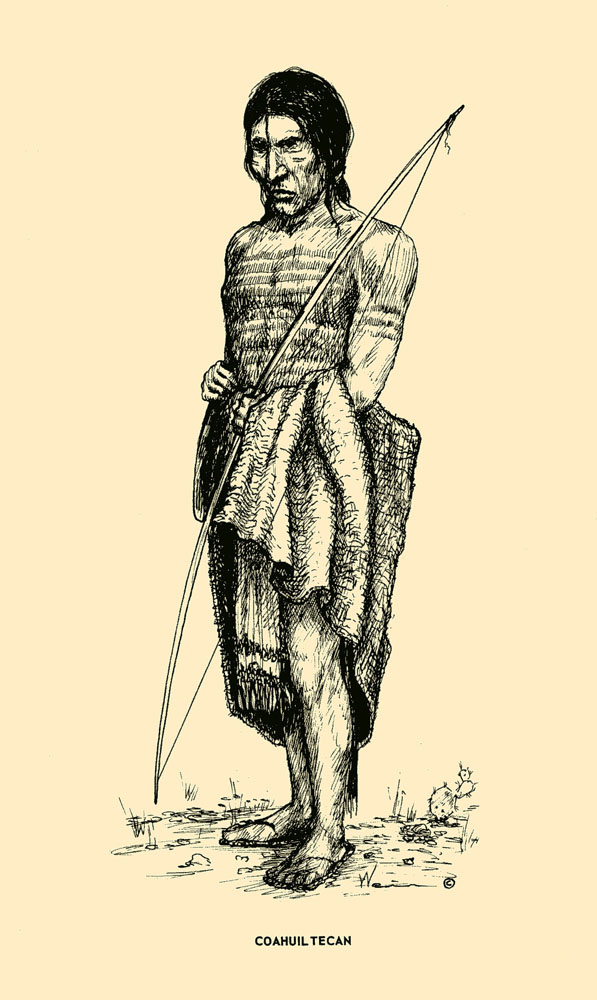

South Texas´ archeological records covering the last 9,000 years are remarkably consistent with what can be gleaned from 16th- and 17th-century ethnohistoric accounts describing how the region´s inhabitants used the landscape. When the first Europeans entered the region, all of the native peoples were hunters and gatherers who probably organized themselves according to lineages and groups of lineages. They lived in temporary villages the Spanish called rancherías that contained from a few to 100 mat-covered dwellings large enough to accommodate one or more families. They moved about the landscape and congregated in accordance with the seasonal availability of staple resources within their homelands, some of which were more than 100 miles across and overlapped with neighboring groups' territories. For subsistence, they depended on wild plant foods”notably prickly pear cactus, various roots, fruits, and nuts” along with game animals”mainly deer, rabbits, and rodents”supplemented by fish, shellfish, and snails, sundry other lifeforms and byproducts and, on rare occasions, by bison. We are fortunate indeed that Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca and his castaway companions, two other Spaniards and an enslaved African, ended up living almost seven years, from November 1528 to September 1535, in the custody of Texas Indians. Following their often harrowing sojourn, they committed their stories to the written word for the King and Queen of Spain and, as it turns out, posterity. These men were history´s sole survivors of an ill-fated Spanish expedition to Florida in 1527 that ended up shipwrecked on Galveston Island. It was in 1537, in Mexico City, when they first recorded their remarkable accounts of Texas Indian lifeways, only a few months after having walked across south-central North America. During their trek from the Texas coast to Culiacán, Sinaloa, near the Gulf of California, they were almost always in the company of the Indians whose homelands and trailways they traversed. It is very likely that the region's native population was, overall, at an all-time high when Cabeza de Vaca arrived. Certainly the trekkers attested to what were clearly very intensive hunting and gathering strategies that must have taxed the productivity potential of the diverse landscapes in greater South Texas. Moreover, they recounted many stories about the almost constant state of mortal, inter-group conflict, whether the groups in question were bands of hunter-gatherers in Texas or farmers in the American Southeast and Southwest who were organized into chiefdoms and tribes, respectively. Said differently, the landscape was comparatively “packed” with humans, relative to its food-yield potential. Everywhere the trekkers lived and traveled in greater South Texas they were told of renowned enemies whose presence restricted where each group could venture. At a time when the first wave of Old World invaders began to penetrate the interior regions of the New World and lay the ground work for conquering the regions´ inhabitants and their lands, the accounts of Cabeza de Vaca and his cohorts are unrivaled in the details they relate about native lifeways in South Texas, including types of food and cooking technology. They attest to hunting deer, eating raw venison, as well as cooking it over an open fire, practices known to outdoor aficionados everywhere. Cabeza de Vaca and his fellow trekkers were the first to document South Texas´ and northeast Mexico´s millennia-old techniques of gathering and baking nopalitos (newly emerged prickly pear“pads”) and green tunas (unripe fruit of the prickly pear cactus) overnight in earth ovens. They recount as well the expertise of Indian women who found and dug a variety of wild root foods, some of which were baked for two days in earth ovens to render them edible, albeit not always tasty. The Spaniards were also probably the first in the New World to commit to writing a description of the ancient cooking technique of stone-boiling, a worldwide practice among hunter-gatherers. While uniquely informative, these accounts are not the be-all and end-all to hunter-gatherer foodways in South Texas, at least not in and of themselves. They are, however, remarkably informative when interpreted within contexts of well-known patterns in hunter-gatherer cooking technologies, the nature and distribution of game animals and plant foods in the region, and the prehistoric archeological record. It would behoove us, of course, to know more about the effects of the Little Ice Age (ca. A. D. 1350-1850) on specific animals and plants, but what we know in general suffices for our purposes here. What is known about cooking technologies during the pre- and post-Columbian eras in regions adjacent to South Texas arguably has relevance to the heartland as well. People from adjacent regions certainly joined heartlanders during the tuna harvest in the early 1500s, and they also participated in the trade fairs that were held there. Cooking has been a family- and community-centered activity since the dawn of human occupation in the New World. Given substantial populations in all parts of Texas for thousands of years, it is unlikely that there were any significant trade secrets in the world of basic cooking technology. In summary, the people of interior South Texas were surely familiar with the types of game animals, aquatic resources, and plant foods found in adjacent regions as well as with the methods the people there used to procure, process, cook, and consume those resources. Indian Nomenclature and Geographic SettingsThere is a long history of debate about the precise route Cabeza de Vaca followed across Texas. Scholars most knowledgeable about the geography and ecosystems of south-central North America, however, conclude that the castaways traversed the heartland of South Texas and northeast Mexico from north to south. Some debate remains about just where in South Texas a particular group was encountered, about the geographic extent of the seasonal rounds of certain coastal or interior groups, and about the seasonality of some plant foods and the identification of others. The details of these debates, however, do not detract appreciably from what can be reliably said or inferred about the nature of native foodways in South Texas as a whole. In this essay, I follow anthropologist Alex Krieger´s interpretations in his posthumously published account, We Came Naked and Barefoot (University of Texas Press, 2002). I believe that, of the various editors and translators of Cabeza de Vaca´s account, he was the best informed about South Texas geography and ecology and probably devoted more time than the others to tracing the route through this part of the state. (Note that in the quotations from the accounts I have used throughout, the brackets are part of Krieger's editing and annotations.) Scholarly discussions continue about linkages between Indian groups encountered by Cabeza de Vaca and his cohorts in the early 1500s and groups living in the same regions during the second wave of Old World invaders in the late 1600s and early 1700s. Some concerns have also been raised about the applicability of the term“Coahuiltecan,” long used as a generalized rubric for the native inhabitants of South Texas and Northeast Mexico. It is because the people of this vast land were organized into dozens of groups, spoke more than half a dozen different languages, had diverse belief systems, and lived in homelands with distinctive food resources that“Coahuiltecan” is sometimes used as an inappropriate ethnic label. (See: Who were the "Coahuiltecans"?) William Griffen, an ethnographer who specialized in native peoples of northern Mexico, traced the 17th- and 18th-century history of hunter-gatherers known collectively as Coahuileños (also Cuaguilos, Coahuilas, and Quahuilas) and documented how the term came to be used, in general, for bands of hunter-gatherers from the frontier province of Coahuila. In doing so, he documents the presence of seemingly once-distinct bands that the Spanish grouped together for administrative and military purposes under a geographic rubric. During the 1600s and early 1700s, Coahuileños operated as a collective or confederacy of sorts when fighting other amalgamated bands or Spanish military forces as well as in suing for peace. As late as the 1740s, the Coahuileños, together with the Tobosos, constituted the principal native groups in the region. “Coahuiltecan” is used in this essay in a geographic sense to denote the groups of hunter-gatherers whose seasonal rounds, if not homelands per se, during the very late pre-Columbian era and the early historic periods encompassed southern Texas and northeastern Mexico from the coast, across the coastal plains, and well into the relatively rugged plateau and mountain country more than 200 miles inland. Among these were the Mariames, Yguazes, and Fig People, bay and coastal groups who lived between Lavaca and Corpus Christi bays. They were geographic Coahuiltecans in the sense that they exploited the extensive prickly pear grounds south of San Antonio and north of the Nueces River. The Charruco, with whom Cabeza de Vaca was based for several years when he served as a trader, were not, however, Coahuiltecans, as they occupied inland tracks well to the north and west (i.e., west of Galveston Bay). While the Charruco probably interacted regularly with Coahuiltecan groups, there is little to suggest that they seasonally occupied parts of South Texas. Cabeza de Vaca also wrote about his trading experiences with the Avavares, a decidedly Coahuiltecan group whose homeland encompassed the south-most bend of the Nueces River, well within the South Texas heartland. The four Old World survivors were to become especially familiar with the Avavares after spending eight months in their South Texas homeland before striking out on their way west across south-central North America. Cabeza de Vaca may have already known the Avavares and neighboring groups from his own participation in trade fairs when he was living with the Charruco. I used to trade with these Indians by making them combs, and with bows and with arrows and with nets. We would make mats, which are things they greatly need and although they know how to make them they do not want to occupy themselves with anything, in order all the while to look for food. -Cabeza de Vaca (Krieger 2002:205). His fellow trekkers may have met them as well when they were in the custody of the Mariames and Yguazes whose homelands were in the vicinity of the lower reach of the Guadalupe River. In This ExhibitIn the following sections we follow Cabeza de Vaca on his long journey across south Texas and Mexico. In Survivors and their Accounts, we learn the backgrounds of the Spaniards and how the fascinating journal accounts came to be written. Initial Encounters details their first, horrific engagement with native peoples. In the three sections following, Roots and Foods of Coastal Foodways, Roots and Fruits of Inland Foodways, and Roots and Road Foods: Deep South Texas and Beyond, Thoms correlates Cabeza de Vaca´s descriptions of food procurement and preparation with specific plants and various modes of processing and cooking he has studied. Rediscovering Heirloom Cookery: Roots of South Texas Foodways provides further information on the author´s research, drawing from firsthand experience and additional ethnohistoric accounts. Credits and Sources provides a wealth of references and links to other sites about the explorer. Kids and older students will find a suite of colorful interactive learning activities in“Through the Eyes of the Explorer: Cabeza de Vaca on the South Texas Plains.” Teach provides a useful lesson plan for history and geography teachers based on Cabeza de Vaca's account. |

|