The Investigations

A High School Student Discovers Burned BonesThe first hint of the archeological potential of Bonfire Shelter came to light in 1958 due to the curiosity of a high school student from Midland, Texas, who had accompanied his parents on a social visit to landowners Guy and Vashti Skiles. Having time on his hands, the high school student grabbed a shovel and a bucket and climbed down into Mile Canyon, intent on discovery. He headed to a place Guy Skiles had shown him, a large rockshelter with a partially fallen roof that was sometimes called "Ice Box Cave" because of its tendency to stay much cooler than elsewhere in the canyon. The mouth of the shelter faced northwest, and massive limestone blocks that had fallen from the roof of the shelter sometime in the distant past blocked even the rays of the late afternoon sun from reaching the floor of the shelter. Guy Skiles, who had explored many of the shelters and caves in the area, had poked around in Ice Box Cave a few times but never found much of interest. All that could be seen on the surface of the cave was dust, goat droppings, broken animal bones, and the scattered remains of a campfire left by goat herders or smugglers earlier in the century. The main path into the cave entered from the south along the cliff and, at the mouth of the cave, visitors could see broken animal bones eroding from the talus slope. These, everybody assumed, must be goat or cattle bones. Mile Canyon had been explored by a team of amateur archeologists from San Antonio's Witte Museum in 1936. Near the upper end of the canyon they noted the presence of a large rockshelter with a fallen roof and a few holes from earlier relic-hunters, but did not notice any archeological evidence. This is the first reported mention of the place that later came to be known as Bonfire Shelter. The Witte Museum team did not linger because its mission was to find interesting, perishable artifacts for public display. They headed to an enormous rockshelter called Eagle Cave, a short distance away from Bonfire Shelter on the opposite bank of the canyon. Eagle Cave was littered with artifacts including many pieces of plant fiber, wood, bone, and even basket fragments, fragile things that are preserved only in the dry confines of the shelter. The Witte crew spent several weeks digging a large trench through the center of the cave and brought back hundreds of artifacts to San Antonio. On display there, the objects fascinated the public and, unfortunately, whetted the appetite of artifact collectors. Soon virtually every large cave and rockshelter in the Lower Pecos had been dug into by relic-hunters, so much so that relatively few undisturbed deposits remained unplundered. Ice Box Cave had remained almost untouched in 1958 simply because "bigger and better" was near at hand and, by comparison, the place didn't look very promising. To the high school student from Midland, however, the fallen roof of the cave begged the question: When did the roof collapse? Were Indians living in the cave before then? So he climbed up to Ice Box Cave and began digging a small hole. The student and several of his pals had been roaming the country around Midland for several years picking up arrowheads which could often be found on the wind-scoured surface in dry west Texas during the drought of the 1950s. Like many people who spend time outdoors, the student became fascinated with these objects, most of which, he knew, represented the tips of darts or throwing spears that Native Americans had hurled with the atlatl or spear-thrower. Guy Skiles had even found fragments of wooden atlatls and dart shafts in the dry caves near Langtry, and this spurred on the student. Arriving at the cave, he picked a spot near its mouth at the top of the steep slope where he could see a few bone fragments eroding out as he climbed up into the cave. As he began digging, the high school student tried to emulate the square holes he had seen archeologists dig. He had already joined the Texas Archeological Society and had been reading books about archeology, especially those about Early Man. Less than a foot beneath the surface he hit bone—lots of bone, and all of it was heavily charred. Many of the brittle pieces he dug up crumbled into ashes as he tried to pick them up. He continued to dig, not sure what to make of all this burned bone. The bone layer wasn't very thick and beneath it he hit a layer of cave dust and rock, similar to the first one he had encountered. After digging a while and not finding any artifacts, the high school student gave up and sat back on the edge of his sort-of-square hole, staring at the layer of burned bones. He wondered what kind of bones he had found and who had set them on fire. Most of the bones looked big and resembled cow bones, but he couldn't imagine why a rancher would destroy so many valuable cattle in such a remote place. He also knew that Guy Skiles mainly raised goats because the land was just too dry for cattle. Maybe, he thought, these were buffalo bones. But why were they burned and why were there so many of them? He brushed the walls of his hole and searched intently for some positive sign, such as an arrowhead, that the bones he had found had been left by Indians. No luck, but he did find a large jawbone with big teeth in it and decided to take it back with him. He was well acquainted with a geologist with the Louisiana Land and Exploration Company back in Midland who knew a lot about animal bones, Indians, too, for that matter. With that in mind, he proudly carried the jawbone back to show his parents and hosts what he had found. To jump ahead of the story, the high school student became so interested in Indian artifacts and the lives of the people that had created them that he decided to major in archeology/anthropology at the University of Texas at Austin in the early 1960s. A few years later, between M.A. graduate work at UT and Ph.D. studies at the University of Arizona, he returned to the Lower Pecos and conducted archeological test excavations at many sites in the area as part of the team from the University of Texas. His dissertation research focused on the stone tools from Arenosa Shelter, another large rockshelter further down the Rio Grande from Langtry. Today, Dr. Michael B. Collins is a well-known expert in Paleoindian archeology and geoarcheology, the use of geological techniques and knowledge to address archeological problems. He is a former Associate Director and current Research Associate at the Texas Archeological Research Laboratory. He is currently leading a major expedition to the Gault site north of Austin. But back to 1958. Young Mike Collins took the jawbone back to Midland and showed it to his friend, Glen Evans, who did indeed know a great deal about animal bones and Indian remains. Evans had trained in paleontology, the study of fossil bones, and worked for many years for the Texas Memorial Museum before turning to the oil business. While working for the museum in the late 1940s and early 1950s, he participated in many paleontological and archeological digs including those at several famous Paleoindian sites such as Blackwater Draw near Clovis, New Mexico, and the Lubbock Lake site. When Collins showed Evans the jawbone, the geologist recognized it as the mandible of the American buffalo, Bison bison. He also guessed that the burning must have had something to do with the prehistoric hunters who he assumed must be responsible for the buffalo bones winding up in Ice Box Cave. This news excited the landowners and their grown son, Jack Skiles, who was then a high school science teacher in west Texas. A few years later, Jack was able to attend UT Austin for one year to broaden his knowledge of science under a special National Science Foundation program. There he learned that a team of archeologists from the University of Texas was conducting research along the Rio Grande in advance of the building of Amistad Dam. Jack knew that more could be learned from a scientific approach than the rather haphazard digging his father did. Therefore, on behalf of his family, Jack contacted the University of Texas and invited the archeologists working at Amistad to come look at Ice Box Cave. Enter the ArcheologistsIn the early 1960s, the Texas Archeological Salvage Project (TASP, forerunner of TARL) at the University of Texas was under contract with the National Park Service to carry out archeological and environmental research in the area that was to be flooded by what was then called Diablo Reservoir (later, Amistad). The lake would be created by the construction of a huge dam across the Rio Grande just upstream from the twin cities of Del Rio, Texas, and Ciudad Acuna, Mexico. Dr. Edward B. Jelks, TASP Director, administered the project from his office in Austin. The field investigations were headed by Curtis Tunnell, then Curator of Anthropology at the Texas Memorial Museum at the University of Texas. (Incidentally, at the time, there was no need to add "at Austin" to the University of Texas; there was only one.) In the fall of 1962 when Tunnell learned of the cave with burned bones in it, he sent Mark Parsons, a young archeologist working for TASP, to investigate. Parsons was in charge of a small survey team that was revisiting known sites and recording new sites in advance of major excavations. Parsons found the shallow hole dug by Collins four or five years earlier and set up a small test pit nearby to try and determine if the layer of burned bones was prehistoric in age. Local rumor had it that the burned bones discovered in Ice Box Cave were the remains of cattle someone had tried to smuggle in from Mexico and that agents of the U.S. Animal Control Service had confiscated. In the late 1940s and early 1950s, there was great concern over the spread of hoof and mouth disease from Mexico into the U.S. Mexican cattle were not allowed across the border except under special permit. And so the story was that a smuggler, some said it was Guy Skiles himself, had been caught trying to take Mexican cattle into Texas and that the Animal Control agents destroyed the illegal animals by torching them in Ice Box Cave. An unlikely story at best and one that the Skiles family obviously knew was false, but the rumors added to the uncertainty. What were so many burned animal bones doing in such a remote place? While exploring Ice Box Cave, Mark Parsons went about formally recording the rockshelter and registering its official designation, 41VV218. (It was the 218th archeological site to be recorded in Val Verde County; the "41" stands for Texas. The naming system, designed by the Smithsonian, is less than prosaic perhaps, but the three-part code makes record keeping much easier.) Within a few hours Parsons had found several stone tools in the test pit including a burned Montell dart point that seemed to be associated with the burned bone layer. The Montell dart point style has a highly distinctive shape and is known to date to the Late Archaic period about 2,500-3,000 years ago. This was the evidence he had been sent to find: apparent confirmation that the bones were prehistoric in age and almost certainly bison (it is very hard to positively distinguish bison and cow, even for experts like Glen Evans). Parsons finished taking field notes about the rockshelter and his small test pit and took off. Tomorrow would be another day and another site to investigate. You might be wondering about the difference between a cave and a rockshelter and why both terms have been applied to the same places. Technically, a rockshelter (shelter for short) is wider than it is deep and a cave is deeper than it is wide. But many folks call any dark hole in the side of a cliff a cave. Archeologists, who as a group are notorious for their ability to spend hours, sometimes days, "splitting hairs" and making ever-finer distinctions, prefer to use the terms correctly. Nonetheless, Eagle Cave is still called a cave even though technically it is wider than it is deep—the name is too ingrained in the local lore. Ice Box Cave, on the other hand, was one of several local names for the locality known today as Bonfire Shelter. The 1963-1964 ExcavationsAt the time, the finding of a thick layer of burned animal bone in apparent association with a Late Archaic dart point was unique in the Lower Pecos. The region was known for its rock art and for the preservation of ordinarily perishable materials, especially fiber and wood, in the dry caves and shelters. Animal bones were common in the cave deposits but the largest animals were usually deer or antelope. Bison bones were rare, and it was assumed that the area had been too dry to support grasslands since the end of the last Ice Age. A thick layer of burned bison bone was unheard of. So Jelks and Tunnell began to plan a major excavation at what they began calling "Bone Cave" or "Burned Bone Cave." (Yes, Ice Box Cave, Bonfire Shelter, Bone Cave, Burned Bone Cave, and 41VV218 are all one and the same place.) David (Dave) S. Dibble, the archeologist chosen to run the excavation at Bone Cave, was new to Texas, having been born and raised in Utah. Dibble had worked on several massive archeological salvage projects in the west under the legendary archeologist, Jessie Jennings. Jennings was famous for his work at Danger Cave, a deeply stratified cave that yielded an almost unbroken occupational sequence dating back to Paleoindian times. Dibble had studied under Jennings at the University of Utah and helped with the analysis of Danger Cave. When he got a call from Jelks, Dibble agreed to come down to Texas and take a look. Dave Dibble arrived in Austin in late August of 1963. As he stepped off the bus, the unfamiliar Gulf Coastal humidity caused him to seriously entertain the notion of hopping on the next bus back home to high and dry Utah. But the lure of an interesting archeological challenge proved irresistible: a mysterious layer of charred buffalo bones in a remote cave and the opportunity to work in a new region. The archeology of the Lower Pecos was still very poorly known at the time, and the Amistad Reservoir work was planned to continue for several more years. The climate of Texas, he was told, was often delightful in the fall, winter, and spring. UT Teams Arrive in ComstockA month later, two archeological teams from the University of Texas arrived in Comstock, Texas, a small ranching town between Del Rio and Langtry. Comstock was the closest place they could find to Bone and Eagle Caves where housing and a work force could be found (Langtry was almost a ghost town). Two young archeologists-in-the-making, Elton Prewitt and Roy Little, were to be Dibble's assistants. Mark Parsons and Richard (Dick) Ross were there to conduct new excavations at Eagle Cave. Curtis Tunnell was along to make sure both excavations got off to a proper start. Housing had to be arranged, local workers hired on for both crews, and so on. On September 27th, preliminary work began at both sites. This meant lugging the digging equipment down into the steep canyon and up to the shelters, setting up screening areas, establishing datums (reference points), and laying out excavation grids. Curtis Tunnell took on the task of mapping both shelters. Elton Prewitt remembers that he and Roy Little spent a day working with Tunnell at Eagle Cave, learning how to map a site with a plane table and alidade. Each young archeologist spent half a day holding the rod and half a day learning to use an alidade, a somewhat awkward surveying instrument that was then the standard archeological mapping tool. (Today most archeologists use computerized mapping tools which seem easier and faster but do not necessarily produce better maps.) At the outset of the excavations at Bone Cave (Bonfire Shelter), the main objective was to investigate the burned bone layer and confirm that it was definitely associated with Late Archaic artifacts. The biggest question, according to the Daily Journal that Dave Dibble carefully kept, concerned the conflagration that had created such a thick layer of burned bones. Was this a natural fire or an intentional pyre? And why here? How did all those buffalo bones come to be in Bone Cave? Was this a jump site? To begin answering these questions, several 10-x-10-ft squares were laid out and excavations got underway. It was soon evident that the burned-bone layer or bed was extensive and that it definitely was associated with Late Archaic dart points and other artifacts. The quantity of the bone was such that a mass kill, probably a "jump," (see Plunge of Death) was the only viable explanation for how so many buffalo wound up in an isolated rockshelter. Studying the topography, Dibble saw that the cliff above the shelter could have served well as a jump and that the buffalo must have fallen atop the rocks (fallen roof blocks) piled at the mouth of the shelter. As the excavation units progressed, a second bone bed was found about three feet below the surface. The newly discovered bone bed also consisted of bison bones, but many of these weren't burned and they seemed to be noticeably larger in size. Was this bone layer evidence of a much earlier jump? Were these the bones of an extinct bison species? By the end of October, substantial portions of the upper part of the deep bone bed were exposed in several different excavation units, and still there was no definite evidence that humans were involved. Dibble's journal entry for October 30 reads, "Today I began to get very discouraged regarding the chances of finding human traces in the deep bone beds ... the evidence seems most suggestive in F7, but still we fail to find anything definite." It was unclear at the time whether they had found one deep bone bed or several because not all the excavation units were connected. Following standard archeological practice, Dibble assigned a separate feature number (e.g., F7) to each exposure. But the work continued and more and more of the deep bone bed was exposed. Finally, on November 20, a finely flaked lanceolate projectile point—a Plainview point—was found directly beneath a bison rib, convincing evidence at last that Paleoindian hunters were responsible for at least one bison jump. Dibble's daily journal entry begins "This was 'D' Day at VV218." It was a Day that Elton Prewitt Will Never Forget (click for story). This crucial find turned the corner, and the archeologists now realized they were uncovering an extremely important archeological deposit. Soon, fragments of additional Paleoindian points were found amid the bones of the deep layer. Dibble also began to notice minor differences in the encasing sediments and the amount of roof spalls amid the bones, indications that Bone Bed 2 had formed as the result of different jump episodes—perhaps as many as three. But this understanding did not come until later. The Winter Work: 1963-1964Although the work plan had called for the completion of the Bone Cave (Bonfire) excavations by Christmas, Jelks found the money within the overall Amistad project budget for a two-month extension. In early January, 1964, excavations resumed. Big, important archeological projects have a way of shaping the careers of archeologists and this was the case for Dibble and many others who have worked at Bonfire Shelter. Dave Dibble was a quiet person who took his responsibilities at Bonfire very seriously. His journal entries reflect a thoughtful, systematic approach. He carefully distinguished between what he had good evidence for and what he only suspected might be true, as if reading his notes later would remind him of doubts and lead him to better interpretations. Crew member Elton Prewitt took advantage of Dibble's good nature by periodically posting new names for the site on cardboard signs at the entrance to the shelter such as "Dibble's Deep Freeze." "Dibble's Dabble" didn't go over too well, because at the time they were still struggling to find evidence that Bone Bed 2 was a bison jump. During that December and January, the Bone Cave crew learned first hand why the place was called Ice Box Cave. Even on sunny days the cave stayed cold, an average difference of at least 10 degrees F. On the days following a norther's cold blast of arctic air, working conditions were miserable. Day after day they worked in the tight confines of 10-ft squares, hemmed in between bones, almost motionless in a cold, dark hole. Elton Prewitt remembers that the campfire area they had originally set up outside the shelter was moved inside and lit as soon as they arrived every morning. He also recalls warming his tortilla-wrapped beans in the coals for a hot lunch. The archeologists continued to probe the shelter's deposits—and probe for answers. Several of the excavation units were dug through the second deep bone bed and still deeper layers of bone were encountered. The deepest layers were collectively called "Bone Bed 1;" it consisted of the bones of various extinct animals including mammoth, horse, bison, camel, and antelope. Based on the depth below Bone Bed 2 and the mix of Pleistocene fauna, Dibble guessed that Bone Bed 1 must date at least several thousand years earlier, well into the latter part of the last Ice Age. But with time running out, they only were able to sample a relatively small part of this deepest bone bed, and no definitive sign of a human presence was found with it. Several out-of-place limestone boulders were found amid the bones along with a number of splintered bone fragments that suggested the boulders had been used as anvil stones. Nonetheless, the absence of chipped stone tools left the question open—and it was to remain open. On February 28, 1964, the fieldwork drew to a close. While the crew collected the last soil samples and hauled away the last bags of dirt and the digging gear, Dibble stared at the excavation walls and reviewed his field interpretations. From his daily journal entry: "The observing of possible layering at the south end of the site has made me wonder if our previous understanding … was not somewhat premature." He was referring to the notion that Bone Bed 2 represented a single event. (He later realized that Bone Bed 2 formed as the result of at least three successive events.) Like all good archeologists dealing with complex deposits, Dibble had to leave the site behind with at least as many unanswered questions as when he arrived. The excavation units were left open, in part because the site was protected by the shelter roof and by the landowner, and in part because of the lingering questions and unexploited opportunities. Was Bone Bed 2 a single event or several closely spaced ones? Were humans involved in Bone Bed 1? Where was the bottom of the shelter? What, if anything, of interest lay below Bone Bed 1? Some of these questions could be answered by the information and samples that were already in hand, but others demanded more fieldwork. In June, Dave Dibble led a small group back to what was now called Bonfire Shelter (the name Bone Cave had already been bestowed on another Paleoindian site). The purpose of the June 1964 trip was to take two pollen columns from the walls of the deepest excavation units. By calculating the changing frequencies of different types of plant pollen through time (up and down the stratigraphic profile at Bonfire, for instance), palynologists can reconstruct past climates and track changes over time. Over the next few years, Dibble worked on the analysis and reporting of the site. A graduate student in paleontology, Dessamae Lorrain, studied the animal bones and tried to reconstruct the original size of the animals, the number of animals, and the herd structure represented by the bone beds. Several reports were written. The first, by Dibble, was sent to the National Park Service to fulfill the terms of the contract under which the work was done. But this technical report was only produced in limited copies; the importance of the site demanded wider distribution. Dibble's report was revised and formally published in 1968 along with a study of the bones by Lorrain. This remains the most important source of information on Bonfire Shelter. 20 Years Later: The 1983-1984 InvestigationsAlmost 20 years after the first major excavations, Dave Dibble's ambition of returning to Bonfire and investigating Bone Bed 1 using more modern excavation techniques was finally realized. Although poor health limited him to only occasional visits to the site during the 1983-1984 work, Dibble served as the Principal Investigator for a team led by Dr. Solveig Turpin. Their mission was to open up a larger area of Bone Bed 1 and to collect samples useful for providing more-precise dating of Bonfire's lower deposits as well as materials that would allow sophisticated stratigraphic, environmental, and climatic analyses. Of course, the driving goal was to find what had eluded the earlier excavations: unassailable proof that humans were involved in the creation of Bone Bed 1. Given the antiquity of that deposit, evidence of that sort would have to be vigorously defended in the larger—and somewhat contentious—scientific community. According to the prevailing "Clovis First" hypothesis, humans had first crossed the Bering Land Bridge from Siberia into North America about 13,500 years ago (11,500 B.C.) and then rapidly spread across the continent. Therefore, claims of cultural remains in North America dating earlier than 13,500 years ago are automatically viewed with suspicion by many Paleoindian experts. For good reason, too, because through the years, many such claims have been shown to be erroneous. A good example is the 1957 report of the Lewisville site near Denton, Texas, where a Clovis point was reportedly associated with several apparent hearths that yielded charcoal which was radiocarbon dated to 37,000 years old. The claim was met with great skepticism and soon dismissed by most as implausible. Years later it was learned that the so-called charcoal that had been dated was actually a mix of wood charcoal and lignite (natural coal, an organic material of ancient origin). Many other claims of great antiquity for humans in the New World have been discredited because of similar and other problems. With this backdrop, you can see why Dibble's hunch that Bone Bed 1 was at least in part the work of humans and probably pre-dated Clovis could only be substantiated by indisputable evidence, preferably stone tools in direct association with the bones and with carefully dated wood charcoal from an obvious hearth. For 20 years Dibble had dreamed about finding "smoking-gun" evidence in Bone Bed 1. Twenty years may seem like a long time to wait, but major archeological excavations are not easy to pull off. While the digging may seem like it ought to be fast and easy, and sometimes it is, many obstacles must be cleared before shovel and trowel come to hand. Landowner permission was easy; Jack Skiles had been waiting for decades for archeologists to satisfy his own curiosity. He found the Ice-age animal bones fascinating in and of themselves, whether or not humans had put them there, and he wanted to learn more about the now-extinct animals that once had roamed the land. And he had vowed not to fill in the deepest 1963-1964 pit until the archeologists returned and hit rock bottom—the original bedrock floor of the cave, the layer beneath which no more bones or artifacts could exist. The Funding ChallengeA bigger challenge was finding the money needed to support a proper dig. Scientific archeology is expensive—perhaps not when compared to the cost of launching a business, or fielding a football team, or building a house, but all those ventures are a great deal easier to fund. Doing archeology is pure research and no one's life depends on it. Returning to Bonfire would take a concerted fund-raising effort and a bit of luck. The original work at Bonfire was government funded, part of the larger research effort conducted in advance of the filling of Amistad Reservoir. But in 1983 there was no such governmental interest in Bonfire—it sits comfortably above the maximum lake level and remains in private hands. Fortunately for our story an unexpected opportunity arose: Author James Michener decided to write a book about Texas and moved to Austin. Michener's earlier book on Colorado had opened with the arrival of earliest humans on the plains of eastern Colorado at about the same time Paleoindians had scared the first herd of buffalo off the cliff above Bonfire. As Michener settled into Austin, speculation had it that he might start his book on Texas in the same way. And what better site than Bonfire to set the scene? According to Solveig Turpin, it was just such thoughts that led UT Austin to decide to help fund a return to Bonfire to finally answer the question the earlier university research project had left dangling: Did Bonfire have the earliest evidence for human presence in Texas? Hoping for a positive answer, modest funds were found at the University to help support the project. These funds were matched by the Potts and Sibley Foundation of Midland. Jane and D.J. Sibley had developed a personal interest in the Lower Pecos and had become acquainted with Turpin and Dibble. And so it was that the funds were raised for the return to Bonfire. The money was just barely enough to cover the minimal expenses assuming that a hungry crew could be found and that major logistical impediments could be overcome with surplus scraps, borrowed equipment, and ingenuity. The hungry crew was assembled in Austin from graduate students and young professional archeologists between contract projects. The pay wasn't much and the hours would stretch long beyond a 40-hour week, but Bonfire already had achieved near mythical status in archeological lore. Bement remembers the surprised look on one crew member's face when he found out that Dave Dibble's promise to pay him "six-eighty" meant $680 per month rather than the princely sum of $6.80 per hour that he had been counting on. The crew agreed to cut-rate pay because they wanted to dig at Bonfire. To get to the bottom of the shelter's deposits and be able to see what they were doing, the archeologists would need some heavy equipment and a whole lot of light. They needed to haul hundreds of pounds of equipment and samples in and out of Mile Canyon. The 1963-64 work had been done on the cheap and done with minimal equipment. One of the constraining factors that had hampered Dibble's first investigations in the deeper parts of the central area of the shelter was the lack of adequate illumination. Good lighting is essential to be able to see subtle differences in color and texture that often provide the most important clues in unraveling complex deposits. And there was the "big rock" problem. The lower deposits at Bonfire contained some very large boulders—some as big as a stove—and weighing up to a ton. If you couldn't remove or move them, you had to work around them, and that was hard to do in the confines of a relatively small excavation pit. Finally, there was the problem of getting the crew in and out of the canyon, day in, day out. During the first dig, everything and everybody came in and out on foot, a fact which cut down on the available excavation time and severely limited what went in and out of Mile Canyon. Solving the Logistical ProblemsThe new investigations at Bonfire were supposed to get underway early in the fall of 1982, but the funding was delayed for several months. Finally in November, 1982, the advance crew arrived in Langtry and began tackling the logistics. Over a period of several months Turpin's team solved every challenge, one by one, mostly through ingenuity and hard work. The budget did not allow them to purchase new equipment or even lease what they needed; instead they had to scrounge and improvise. The 1963-1964 team had come in and out of the canyon the long way, following established goat trails down the opposite canyon wall, through the canyon, and up to Bonfire. This required at least 45 minutes each way, more if it was particularly hot or if you were carrying much. The 1983 solution was to enter Bonfire Shelter almost the same way the buffalo did—straight down the cliff—and, unlike the beasts, the archeologists and their supplies left the shelter each day and took the opposite route—straight up the cliff. Equipment was hauled down and samples hauled up with the use of a heavy winch truck, parked at the top of the cliff. Electricity was provided by an Army-surplus, 4-wheel drive, 24-volt truck fondly and cursedly known as the "Elephant." A large spool of heavy electrical cable was donated by the University—someone had ordered too much for a campus construction project. Banks of lights were assembled from used materials found at University Surplus. And so on. The winch truck would work for equipment, but people required a different solution. A very long ladder was constructed out of galvanized pipe and heavy rebar. Crew chief and logistical "jefe" Herb Eling was the only archeologist on the crew who already knew how to weld. Using his arc-welder and Jack Skiles' acetylene torch, the crew learned how to weld as they laboriously assembled sections of a sturdy ladder that would span over 80 feet when completed. As they welded rebar rungs to the pipe uprights, Bement recalls thinking about what could happen if one of the rungs gave way while he was climbing the ladder: ...splat! Each weld was checked and rechecked. Finally the sections of the ladder were joined and it was time for the installation. They chose a spot that required the shortest span of ladder to get people up and down the cliff. This meant placing the ladder on a section of the cliff that was truly vertical. Eighty feet down and "splat" without a ladder, just like the buffalo. Using the winch truck, they lowered the ladder into place and then, dangling from a steel cable, they used a star drill to attach rebar "legs"—supports that tied the ladder to the cliff. During trial trips up and down the ladder, the swaying to and fro proved unnerving so additional supports were added. Still, it was intimidating. Lee Bement admits that he was afraid of heights and not at all thrilled about the prospects of going up and down the ladder daily. Making matters worse was the fact that the top of the ladder was actually well below the cliff top, in a place where the terrain sloped steeply before the vertical drop. In other words, you had to climb partway down the steep slope before getting to the top of the ladder and then look down to a straight drop. At first the crew used a safety belt clipped to a rebar rail that ran beside the ladder, but this routine made going very slow and cumbersome and was soon abandoned. Within the first few weeks, the ladder became routine for everybody, even Bement. Well, almost everybody. One woman refused to even consider making the climb down until after dark, when she could not see what lay below. Bement himself found it much easier to climb the ladder in the blissful darkness. Within the shelter, the logistics were almost as challenging as the cliff itself. The new excavations would expand on the deepest excavation unit in the central area of the shelter. To remove buckets of soil and move heavy boulders out of the way within the increasingly deep excavation unit, a heavy pipe was suspended above the hole using A-frame supports welded in place. A heavy block-and-tackle was attached to this to hoist backdirt—soil removed from the excavation—and roof spalls out of the hole in heavy-duty, 5-gallon buckets and then placed on an improvised mining trolly (low cart). The loaded cart was trundled along on a wooden track that ran alongside the old excavation units. At the end of the track, the buckets were emptied into the southernmost excavation units left open in 1964. Artificial lighting allowed the crew to work on into the night. They had banks of fluorescent lights and incandescent lights and learned to alternate these to "pull out different strata." Bement explained that under the incandescent lights you could discern bone and darker zones in the excavation profiles, while the fluorescent lights proved better for examining lighter colored lenses. Using these different wave-length lights, the 1983-1984 excavators were able to make out subtle stratigraphic details not seen by the earlier investigators. Search for the Smoking GunThe excavations finally got underway in January of 1983. After cleaning out the old units and opening up two new ones adjacent to the existing hole, the early bone beds were finally reached. The main excavation block encompassed some new ground as well as part of the 1964 unit that had only been excavated through Bone Bed 2. This meant that the excavation block had to be taken down in different segments. The new units exposed more of Bone Bed 2 at the same time that renewed excavations in certain of the older units were encountering Bone Bed 1. The complexity of the deposits soon became apparent. Having more time, better lighting, and larger exposures, the 1983 investigators defined more layers than could be accommodated using the original labeling scheme. A new system was devised and Bone Beds 2 and 1 were redefined as a series of bone-bearing strata that included three layers within Bone Bed 2 and five additional layers that lay within and below the original Bone Bed 1. The excavations were painstakingly slow, even taking into consideration the logistics. Each significant bone fragment (aside from the smallest unidentifiable scraps) was carefully exposed and then immediately coated with a penetrating preservative that held the fragile bones together. Once solidified, the bones were plotted on a map and removed. Larger and more-fragile bones had to be jacketed in plaster of Paris. The enveloping soil matrix was removed and screened to search for small bones and stone tool fragments. But try as they might, the excavators could find no stone tools—large or small—below Bone Bed 2. Nor did they find a hearth or other definitive human construction. What they did find was tantalizing. Limestone blocks bigger than a basketball around which were arrayed the broken and splintered long bones of extinct bison, horse, mammoth, and camel, among others. Some bones looked like they had tiny cut marks from stone tools. Others looked worn at one end and were thought to represent bone tools. But no smoking gun. By April of 1983 funds had run out and the excavations were not completed. They still had more of the lower bone-bearing strata to dig through, and they had not even come close to the bottom of the shelter. Over the next year a small amount of additional funding was secured and in April, 1984, the crew returned for a final four-week stint. Although some of the most interesting and intriguing arrangements of bones and limestone blocks were found, there was still no smoking gun. As time ran out, the archeologists dug a small test pit in the deepest area of the excavation block to try and reach "rock bottom" and make Jack Skiles happy. Deeper and deeper they dug until they reached a large boulder covering most of the floor of the excavation hole. Was this the bottom of the cave? Bement worked down one corner of the unit around the boulder and then stuck his arm down as far as he could go. The fill he pulled up from the lowest point he could reach was composed of water-smoothed gravels, evidence of a time when the floor of Mile Canyon was at a much higher level relative to its modern floor. Floodwaters had obviously pushed into the shelter at that time and left behind the gravels. But was this really the bottom? There was no time left to dig. So Jack Skiles welded together two pieces of rebar to form a long rod. This he hammered down into the small hole Bement had dug and into the gravels. At six feet below the deepest point Bement had reached, Skiles could drive the rod no further. Had he reached bedrock or another boulder? The 1983-1984 field investigations ended without a definitive answer to that question and without a smoking gun. Many other objectives had been met that made the work more than worthwhile. The layering of Bone Beds 1 and 2 was now well documented. Over 400 bones had been documented and collected. Soil column samples were collected for pollen analysis, sediment analysis, and microfaunal (small bones) analysis. Samples of charred bone and wood were collected for radiocarbon dating. Lee Bement took on the analysis of the bones for his M.A. thesis project; the published version served as the final report on the 1983-1984 work.

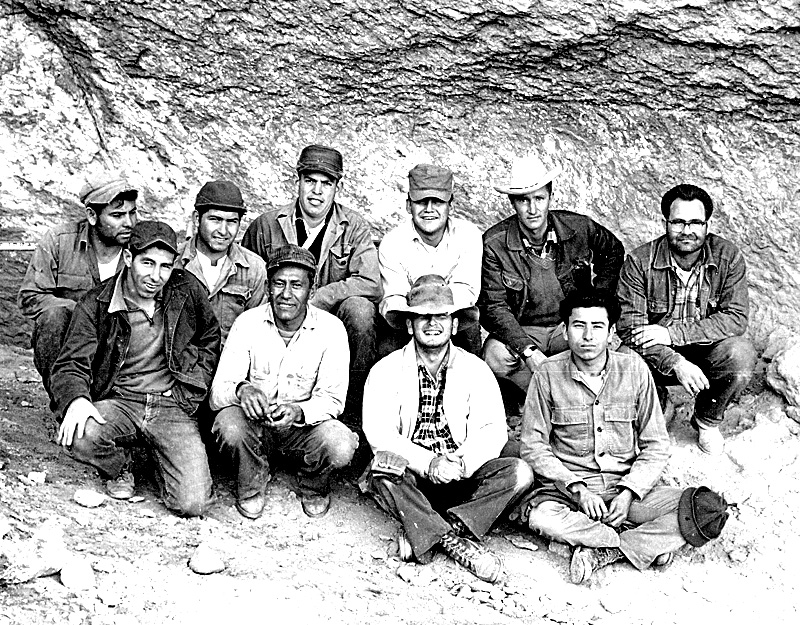

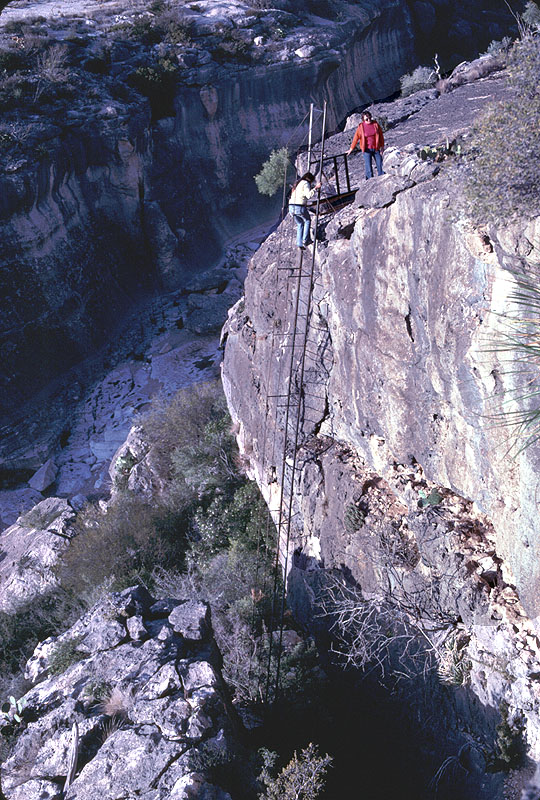

Jack Skiles listens to Prewitt's plan for

preventing further erosion of the talus cone deposits at Bonfire.

Remnants of the black-mesh landscape cloth used in an earlier

attempt to stabilize the deposits are visible.

The 1990 Stabilization ProjectThe 1983-1984 work had filled in many of the original excavation units and helped protect the remaining deposits, but one problem area remained. Occasional heavy runoff had caused considerable erosion in the talus slope area where Bone Bed 3 was concentrated. This area had been partially covered with a black-mesh landscape cloth in an earlier attempt to protect it from erosion, but the cloth had deteriorated. In 1989, Elton Prewitt visited Bonfire for the first time since 1973 and was shocked at the amount of erosion on the talus cone. In 1990, with a $250 grant from the Donors' Fund of the Texas Archeological Society, he organized a return to Bonfire to stabilize the talus cone deposits. Burlap bags were sewn together to form a protective covering that was draped over the slope. A layer of heavy, orange plastic safety netting was added to hold the burlap covering in place. Rocks and metal stakes were added to hold down the edges of the protective covering. The result has proven effective. |