The Britton Site (41ML37)

The Britton site is located in the first terrace within a broad meander bend of the North Bosque River. Beneath a mantle of recent flood deposits, excavators found multiple Late Archaic components buried in 275-cm-thick alluvial sediments. Three analysis units were defined, based on calibrated radiocarbon dates, distinctions within the soil (soil horizons), and a clear vertical separation of the deepest component. Together, the evidence from the three components reflects a 1,140-year span of occupations from 390 B.C. to A.D. 750.

Hunters and gatherers initially camped within an overbank, or channel margin, environment around 390 B.C., which at the time was rapidly aggrading, or building up, but then began to stabilize around A.D. 0. Surface stability and occupations after this time resulted in the formation of artifact-dense Analysis Unit 1. Of particular interest in this unit is possible evidence of a simple structure.

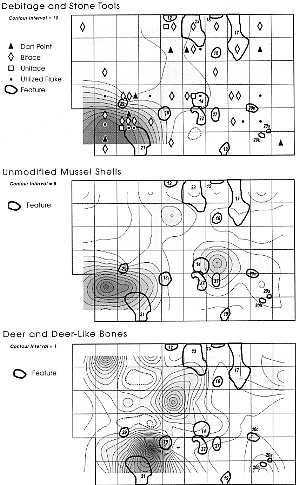

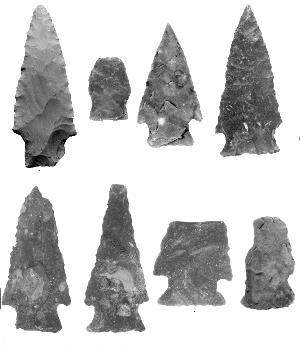

Comparing evidence from the three units, there appears to have been little change in subsistence and technologies over time, with few nuances. Generally, Analysis Unit 1 yielded more lithic artifacts, Analysis Unit 2 generated the greatest numbers of bones and mussel shells and higher burned rock densities, and Analysis Unit 3 produced very low frequencies of each material class. Godley and Ensor points are prevalent at the site, yet interestingly, these types were made of different kinds of chert. Cooking features are dominant and tend to be small (usually less than 100x100 cm, or a little over a yard in diameter). These probably were individual family hearths. The animal bone and plant remains provide evidence of a broad-based diet and varied subsistence strategies. Effort was spent procuring and processing game, particularly deer, based on its abundance among the identifiable bones. Concentrations of spirally fractured elements and fragmented unidentifiable bones are evidence of marrow extraction and grease rendering. Mussel shells, acorns and perhaps other nuts, bulbs, and other plants with edible parts (notably knotweed and pokeweed) were part of the diet. Among the bifacial chipped-stone tools, dart points and scrapers are prevalent. Utilized flakes also are much more common than any single formal tool class, and there is very little evidence that early-stage stone tool manufacturing took place onsite.

The sections below provide a more detailed accounting and interpretation of the evidence from the site.

Features

Consistency in the features and material culture can be seen over the course of the occupations. The prevailing feature types—basin-shaped hearths, flat hearths, and basins with sparse or no burned rocks—are all considered cooking facilities. They constitute two-thirds of all features discovered at the site and comprise 63 to 86 percent of the features within any given analysis unit. Although a greater number of flat hearths are in Analysis Unit 1 and more basin-shaped hearths occur in Analysis Unit 2, generally their morphologies and contents, particularly size, depth, burned rock density, and charred macrobotanical remains, do not suggest functional differences. Generally, these hearth features are small, less than 100 cm in diameter, and probably represent individual family hearths where daily food preparation took place, rather than bulk processing of large amounts of food resources. Excluding stains, the function and origin of which are unclear, most other feature types, including burned rock concentrations, discard piles, and mussel shell and refuse dumps, may be associated with cooking activities.

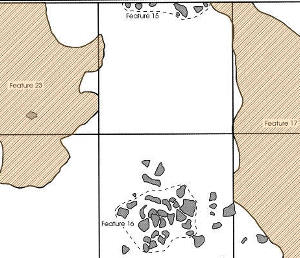

Unique to Analysis Unit 1 are a series of burned surfaces which, based on their size and spatial relationships to other features, may represent a shelter. The shelter was probably a simple pole and brush- or grass-covered structure that was burned intentionally or by accident. Either way, the fire fortuitously left archeological remains of an element of prehistoric hunter-gatherer life that is rarely observed in the region. The graphic shown at right (near the top of the page) illustrates the relationship of the burned areas (Features 17, 23, and 27). In profile, the base of each feature ranges from flat to irregular. Charcoal retrieved from a flotation sample from Feature 17 yielded a conventional radiocarbon age of 1840±50 B.P. Although these features are extensive, they contain sparse materials: one canid- to deer-sized mammalian bone fragment and one deer- to pronghorn-sized artiodactyl phalange (both spirally fractured), one knife fragment, six flakes, and four unmodified mussel shells.

Given the irregular shapes and sizes, and their spatial and contextual relationships to Feature 16 (a flat hearth), it is conceivable that Features 17 and 23 represent some kind of structure. The distance between the two burned surfaces is fairly consistent with the diameter of simple pole and brush shelters, like the dry-season temporary huts of the !Kung or the dry-season huts of the Hadza which provide shelter for small nuclear families. At what may be interpreted as the opening to the structure is a flat hearth (Feature 16), and out in front of it is a refuse dump (Feature 14). This spatial patterning of structure, hearth, and refuse dump is consistent with what is seen at camps of hunting and gathering groups throughout much of the world (see Research Approaches for more detail on modern-day hunter-gather groups). It would be fortuitous for such a structure composed of perishable materials to leave any archeological remains unless it was set ablaze intentionally or accidentally, which could be the case here.

Artifacts

Stone tools and unmodified debitage dominate the artifact assemblages, although the density is 2.7 times greater in Analysis Unit 1 than in Analysis Unit 2. Although the artifacts from Analysis Unit 1 appear to signal a greater focus on lithic tool production and maintenance, nearly equal tool-to-debitage ratios suggest that this difference is not a reflection of the lengths of occupations. Conversely, Analysis Unit 2 has densities of unmodified bones and mussel shells, along with burned rock weights, that are 1.3 to 1.6 times greater than those in Analysis Unit 1. The slightly higher faunal and burned rock densities in Analysis Unit 2 may correlate to the greater number of features found and their association with food processing and cooking. Overall, Analysis Unit 3 has extremely low frequencies of all material classes when compared to Analysis Units 1 and 2. Not surprisingly, the lowest densities represented by Analysis Unit 3 correspond to a time of rapid alluvial deposition and likely reflect infrequent, short-term occupations.

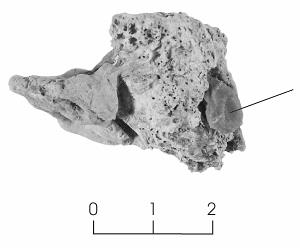

Analysts examined the counts and relative proportions of various chipped-stone tool types and chipping debris to help evaluate subsistence strategies and technologies. The following discussion omits Analysis Unit 3 because its sample is so small. Of the formal tools, bifacial tool forms—projectile points and other bifaces—are most common. Ratios of finished formal tools (excluding indeterminate bifaces) to unmodified debitage are 1:46 for Analysis Unit 1 and 1:47 for Analysis Unit 2. A slightly higher number of formal tools than expedient flake tools is found in Analysis Unit 1, but this ratio is nearly equal in Analysis Unit 2. Scrapers (unifacial and bifacial), dart points, and utilized flakes are common in each analysis unit. The ratios of scrapers to dart points and scrapers to utilized flakes are 1:2.3 and 1:3.7 for Analysis Unit 1 and 1:1.3 and 1:4.0 for Analysis Unit 2. Although the functions of the utilized flakes are unknown, their small size and the rarity of multiple working edges suggest that they were used for short and simple tasks. The prominence of projectiles (including one fragment embedded in a deer skull) and scrapers indicates a tool kit geared toward hunting and game processing. No additional specialized activities are apparent, since the other formal and expedient tools (excluding the indeterminate bifaces) each constitutes less than 4 percent of either assemblage.

Lithic procurement and reduction strategies are interpreted from biface, core, utilized flake, and unmodified debitage attribute data. Combined totals for Analysis Units 1 and 2 reveal that 11 percent of the bifaces are early-stage reduction specimens, and 56 percent consist of late-stage and finished specimens. Of the small sample of cores (n = 12), Analysis Unit 1 contains twice as many as Analysis Unit 2. Approximately equal numbers of small complete cores with more than 50 percent cortex and larger specimens retaining less than 50 percent cortex are represented. The debitage assemblages are characterized by small (1.0 inch or less) decorticate flakes. Altogether, these data suggest that most formal tools were brought to the site as late-stage or finished specimens and that primary reduction occurred away from the site area.

The finished tools, such as dart points, also tend to display intense use and a high level of resharpening, the result of having been used at the Britton site and probably at other locales prior to their discard at Britton. Because bifacial tools are durable, versatile, easily transportable, and amenable to multiple cycles of resharpening, thus extending their use lives, they can be used at multiple locales across the landscape. Such advantages make them ideal for highly mobile groups, lessening their need to be closely tethered to sources of suitable lithic materials. Conserving the working edges of formal tools and thus extending their use lives can also be accomplished by the use of expedient flake tools. Most of the utilized flakes in both analysis units measure 1 inch or less and thus probably were used to complete simple tasks, but tasks nonetheless that did not expend formal tool edges. Abraded cortex characteristics on some of the utilized flakes suggest that they were struck from small chert gravels collected from local gravel bars, and the use of these gravels can be viewed as a strategy to extend the use lives of formal tools.

Lithic material attributes of the dart points present an interesting insight into the access and procurement of lithic materials and possibly group identity. Ensor and Godley dart points from Analysis Units 1 and 2 show exclusive use of distinctively colored cherts for the production of these point styles. If point styles serve as social identity markers, then this presents an additional argument that the two point types may have been manufactured and used by at least two different groups. Because the two different colored cherts often occur together on gravel bars throughout the lower Bosque basin, their exclusive use for one point type and not the other is not an issue of access, but rather may have been a conscious attempt to portray distinct social identities.

Other artifact types are found at the Britton site in addition to formal and expedient chipped stone tools. The ground and battered stone tool assemblages are composed of 7 manos, 2 mano/hammerstones, 2 stones with at least one ground facet, 1 pitted stone, and 2 hammerstones. Use wear is minimal on these tools, which is consistent with the idea that their weight precluded their transport from site to site. The grinding implements were probably used for plant processing, although the evidence for this is not overwhelming. Modified bones include 2 awls, a split and grooved element, and a pressure flaker, and 12 modified or possibly modified shells consist of drilled or cut valves. The modified faunal remains show a clear distinction in that bones were fashioned into tools and shells were drilled and cut for ornamental purposes.

Animal and Plant Remains

The vertebrate animal bones recovered indicate that hunting centered on deer and to a lesser extent antelope. Deer, deer family, deer- to pronghorn-sized artiodactyl, and canid- to deer-sized mammal remains predominate. For the most part, it appears that whole or dressed deer or antelope carcasses were brought back to the site and processed. Deer and deer-sized elements from Analysis Unit 2 provide insights into the butchering process, with the removal and distribution of the forelimbs and hind limbs as meat and marrow-rich bone packages and the stripping of meat from the axial elements. The meat and marrow packages were processed away from the primary butchering areas, as evidenced by the proveniences of long bones with cut and impact marks. Deer were intensively processed and used, as one-fourth to one-half of the elements exhibit spiral fractures indicating breakage for marrow extraction. Numerous unburned fragmented bones from feature contexts suggest grease rendering as well.

The variety of animals exemplifies the diverse fauna available along the riparian corridor of the North Bosque River and the river channel itself. All three analysis units yielded a variety of terrestrial, aquatic, and avian (bird) taxa. Beaver, however, only occurs in Analysis Unit 1, and a possible bison-sized mammalian element, waterfowl, freshwater drum, and gar are only present in Analysis Unit 2. Deer were the highest-ranked resource and primary target. Other fauna were lower ranked and were used toward the end of occupations, once deer in the site area were depleted and their acquisition costs increased.

Mussel shells also were found in abundance. More than 1,200 unmodified valves were recovered and, of these, 10 percent were analyzed. Only 12 valves were unidentifiable, indicating excellent preservation of the umbos (hinge area of the bivalve shell). The same species are present in each analysis unit excluding Washboard, which only occurs in Analysis Unit 2, and False Spike, which is absent from Analysis Unit 3. In each analysis unit, Threeridge is abundant, comprising more than half of the valves. Louisiana Fatmucket, Pistolgrip, and Smooth Pimpleback are also common. These four species commonly occur in medium-sized and large rivers and can live on various strata, including gravel, mud, and sand. The overall number of shells and consistency in species represented indicate that the North Bosque River supported viable populations that were a reliable resource through time. Despite their prevalence, however, caloric values indicate that mussels were never a major source of food but were probably a small part of the daily diet based on discrete shell piles and clusters that are viewed as the remains of individual or family meals. In one context, Rabdotus sp. shells are plentiful in a mussel shell dump, suggesting that the gastropods were deliberately collected and eaten.

Macrobotanical analysis was conducted on flotation samples obtained from 3 features from Analysis Unit 1; 21 features from Analysis Unit 2; and 4 features from Analysis Unit 3. Ash, hickory/pecan, and plateau live oak wood are found in each analysis unit, with juniper, mesquite, and sumac only absent from Analysis Unit 2. Further examination of the wood types from the largest sample in Analysis Unit 2 reveals that hickory/pecan and at least one type of oak wood are each present in 15 features. Another common wood is elm and elm/hackberry, occurring in 13 features. The occurrence of these woods signals their prevalence in the area. The hickories, pecans, and oaks in particular would have offered abundant nuts and acorns. Other food-bearing trees are represented, including mesquite, persimmon, and plum/cherry. While the wood of food-bearing trees is present, the actual remains of botanical food stuffs, such as seeds, acorn nutshells, and grasses, are rare in Analysis Units 1 and 3. Charred seeds of the mallow family, pokeweed, prickly pear, and stretchberry indicate plants with edible components. Parts of knotweed, pokeweed, and prickly pear can also be used for medicinal purposes and as a dye, spice, or insulating material in cooking. Six basin features contained bulb fragments.

The floral, or plant, assemblage from Analysis Unit 2 displays wider variety than those of Analysis Units 1 and 3. This diversity most likely reflects the greater number of samples submitted for analysis from Analysis Unit 2, since several identifiable plants occur in at least two analysis units. Thus, it appears that each analysis unit would produce comparable results given equitable sampling, particularly sampling of cooking features. Lipid residue analysis performed on burned rocks substantiate the macrobotanical findings. The lipid residues are similar to nuts and seeds and possibly akin to cholla and mesquite.

Summary

The investigations at the Britton site reveal multiple short-term occupations by hunting and gathering groups during the latter half of the Late Archaic period. Site activities appear to have changed little through time. Differences in lithic material sources used for the production of Ensor and Godley dart points suggest that different groups used the Britton site, perhaps at different times of year. Seasonal use of this dynamic setting was geared toward exploiting the flora and fauna occupying the rich riparian floodplain, with probable forays onto the adjacent uplands, until the cost of obtaining these resources exceeded the returns. Of the resources used, deer, and to a lesser extent antelope, appear to have been the primary hunting target, although mussels, small game, and plant foods augmented this diet. The technologies used to carry out the daily food quest and tasks of food preparation largely consisted of a portable tool kit of bifacial tools and rock-lined hearths. The tool kits supported a highly mobile lifestyle, as these tools are amenable to multiple cycles of use and retooling, thus extending their lives and their use at multiple locales across the landscape. The small size of the hearths suggests that the features were individual family hearths that provided a means by which various foods could be processed for immediate or later consumption. They also probably served as the loci of individual family activities.

|

|

|

|

|

|