Rosillo Peak

The Rosillo Peak site (41BS762) is located in a small saddle on the summit of Rosillo Peak, the tallest peak in the Rosillos Mountains, on the northwestern edge of Big Bend National Park (BBNP). It is one of only a handful of well-documented sites in the eastern Trans-Pecos that dates to the Middle Archaic period, and only one of three that has been excavated using modern field and analytical techniques. Over a span of some 5,000 years small groups of hunter-gatherers repeatedly hiked to the summit of Rosillo Peak and established temporary camps. But what drew them to this remote site again and again over the years is not entirely clear.

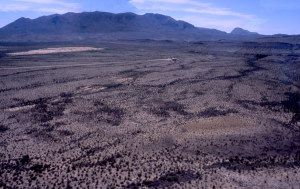

Though not the tallest range in the area, the Rosillos Mountains are nonetheless dramatic, rising 701 meters (2,337 feet) above the surrounding desert basin. At 1,660 meters (5,533 feet) high, Rosillo Peak is the highest peak in the range. The exposed bedrock of its summit and the many boulders that litter the upper slopes have been rounded by wind and water, giving the site a somewhat surreal appearance enhanced by stunning vistas of the surrounding mountains and basins. Contributing to the dramatic atmosphere is a prominent pinnacle of rock on a narrow ridge that appears to the naked eye to be the highest point on the summit (measurements revealed that it is actually 50 cm (20 inches) below the highest point).

Archeological sites on mountain peaks are not unusual in the Big Bend and other parts of the eastern Trans-Pecos. Archeologists in the region have found small circles and piles of rocks, special caches (offerings) of projectile points, small concentrations of stone tool-making debris, and other relatively ephemeral cultural remains on peaks. Because of the lack of water, and formidable settings that do not seem conducive to habitation or to normal daily activities, archeologists usually infer that these sites have been used for ritual purposes. During the Late Prehistoric era, roughly 600-1000 years ago, mountain ritualism became an important aspect of lifeways in the Big Bend. Rosillo Peak is unusual in this regard, because it dates mainly to the Archaic period and contains the remains of a full-blown campsite, yet these remains lack certain debris which occur in the foothill and desert floor campsites found below.

Until 1984, the Rosillos Mountains were part of the North Rosillos Ranch, owned by Houston and Edward Harte. The Hartes were interested in the history and prehistory of the area, so they asked the Office of the State Archeologist (OSA) at the Texas Historical Commission for help. This led to an archeological reconnaissance of the Rosillos Mountains funded in part by the Hartes. In the spring and summer of 1979 and summers of 1980 and 1982, the OSA conducted field sessions in the foothills of the Rosillos Mountains and the surrounding basins. The Rosillo Peak site was discovered in July of 1980 during an exploratory excursion into the higher elevations of the mountains. At the time, investigations at the site were restricted to recording and limited surface collection.

Over two decades later, research opportunity knocked again. The area had become part of Big Bend National Park and the park’s law enforcement division joined with the U.S. Border Patrol in 2004 to propose placement of a radio repeater facility on Rosillo Peak to improve radio coverage in the area. Construction and maintenance of the proposed repeater would impact a portion of the Rosillo Peak site, so BBNP contracted with the Center for Big Bend Studies (CBBS) to carry out further research according to a plan devised by park archeologist Tom Alex. In March of 2005, archeologists from the CBBS under the direction of Robert Mallouf created a detailed map of the site, conducted a thorough surface collection, and performed test excavations. Because of the remoteness of the site, the archeologists and their equipment had to be shuttled to and from the summit in a helicopter provided by the U.S. Border Patrol. The results of the work were published in 2006.

Rosillo Peak was found to have a discernable midden area containing scatters of debitage, burned rock, and stone tools. The 2005 excavations at the site uncovered burned rocks (spent cooking stones), a few chunks of charcoal, and six burned bones, suggesting the presence of buried hearths. The bones could not be identified, but appear to belong to rabbit or deer-sized mammals. Radiocarbon assays taken from one chunk of charcoal and two sediment samples yielded calibrated age estimates of 1210-920 B.C., A.D. 540-670, and A.D. 680-1000.

Due to poor organic preservation on the mountaintop, the artifact assemblage from Rosillo Peak consists entirely of chipped-stone tools and tool-making debris. Nearly 5000 artifacts, including 221 tools and tool fragments, were recovered from the site by the 1980 and 2005 investigations. The stone tool assemblage contains an unusually high number of dart points and dart point performs, and a correspondingly low number of other bifaces and unifaces. The site’s tool-making debris is not particularly dense or numerous and contains few cores. Analysis suggests that the finishing of performs and maintenance of dart points were the primary knapping activities that took place at the site.

The dart points recovered from Rosillo Peak include Arenosa, Shumla, Figueroa, Pandale, San Pedro, Conejo, Frio, Almagre, Langtry, and Gobernadora points. These types span the Early, Middle, and Late Archaic periods and broadly date the site to between 3500 B.C. and A.D. 700. In addition, three fragmentary Perdiz arrow points were found, indicating a brief Late Prehistoric occupation sometime between A.D. 1250 and 1750. The Pandale, Shumla, and Figueroa points are uncharacteristically small and show no evidence of reworking, suggesting that intentional manufacture of diminutive dart points was taking place at the site. This cannot be explained as the result of the conservation of tool stone, because there are several sources of high-quality stone in the foothills of the Rosillos Mountains.

Two fragmentary manos and three slab metates were also found at Rosillo Peak. Much more prominent than these portable grinding stones are the site’s 17 “boulder metates.” These basin-like “slicks” in the site’s boulders appear to have been created by the natural weathering effects of wind and water and required little or no preparation to be used for grinding. Repeated grinding gave the basins an artificially smoothed concave appearance. Although no plant residue could be recovered from the boulder metates for analysis, they were likely used to grind grass seeds gathered from the grasses that blanket the summit. Considering the large number of boulder metates at the site, the small number of stone manos is surprising. The people who camped at Rosillo Peak may have used perishable wooden manos that have not preserved in the archeological record.

Prehistoric hunter-gatherers first camped at the summit of Rosillo Peak in the Early Archaic period, then returned to the site periodically for thousands of years. Judging by the large proportion of Middle Archaic dart points in the site’s projectile point assemblage, this was the period of maximum use of the site. But the exact nature of these occupations is unclear.

In some ways, Rosillo Peak resembles an Archaic campsite where life’s daily tasks were carried out—seeds were ground, small to medium-sized mammals were cooked and consumed, dart points were finished and retooled. But the site lacks the plant-working and expedient tools that are so common in most Archaic campsites, and has very few of the tool forms that would have been needed for the collecting and processing of food stuffs. Instead, the Rosillo Peak stone tool assemblage places an overwhelming emphasis on projectile point manufacture and maintenance.

Rosillo Peak is an impractical location for an ordinary campsite, situated nearly 500 meters (1,667 feet) above the closest spring and completely exposed to the elements. It offers no resources that could not have been obtained in greater quantity from lower elevations of the Rosillos Mountains. As a hunting observation spot it would seem to offer little advantage—any animals that were spotted would have taken hours to reach.

It seems more reasonable to suggest that Rosillo Peak was not an ordinary campsite at all. The dramatic atmosphere of its summit would have facilitated ritual activities, only a few of which may have left archeological signatures. In a rugged landscape where mountain peaks are visible from many miles away, it makes a lot of sense that certain promontories would have been seen by hunting and gathering peoples as special places imbued with sacred meaning.

One archeological pattern at Rosillo Peak with possible ritual significance is its large quantity of dart points and preponderance of unusually small ones. Perhaps these diminuitive dart points were valued as symbols rather than functional weapon tips. It is curious that the site seems to have been utilized most during the Middle Archaic period, several thousand years before mountain ritualism reached the height of its importance in the region in the Late Prehistoric period. This suggests that the symbolic importance placed on peaks by the people of the Big Bend has ancient origins in the region.

Contributed by Carly Whelan based on a report by Robert Mallouf and others cited below.

Sources

Mallouf, Robert J., William A. Cloud, and Richard W. Walter

2006 The Rosillo Peak Site: A Prehistoric Mountaintop Campsite in Big Bend National Park, Texas. Papers of the Trans-Pecos Archaeological Program Number 1, Center for Big Bend Studies, Sul Ross State University, Alpine; Big Bend National Park, National Park Service.