Los Almagres, the Lost Spanish Mine

Silver! Enough for every person to own a silver mine! So wrote Bernardo de Miranda y Flores in his 1756 report to the Spanish provincial governor after visiting Cerro del Almagre and Los Almagres, a mine near the Llano River. Almagre is a Spanish word that means "ochre", and Cerro del Almagre means a Mountain of Ochre. Ochre is rock composed of concentrated iron oxide minerals and is sometimes associated with precious metal ores—including silver. In 1753, a small group of Spaniards excavated a pit at this site. Later, the governor asked Miranda to visit and examine the site. Miranda cleared the pit, extracted samples, and had them assayed. Although the results showed little silver, Miranda was convinced that silver-bearing ore could be extracted in large quantities because of the extent of iron oxide rock he observed. Unfortunately for the Spaniards, this land was occupied by Apaches who killed prospectors in the area during the next few years.

In 1757, a presidio was constructed along the San Saba River near the present town of Menard, a few miles from Mission Santa Cruz de San Sabá (see associated Historic Encounters exhibits on these sites). The mission was attacked and destroyed by Comanches in 1758, and the presidio was abandoned. Although there were several visits to the Los Almagres area during the remainder of the century and into the 1800s, little actual prospecting for silver took place, and Miranda's site, Los Almagres, was essentially lost. Unfortunately, Stephen F. Austin showed San Sabá presidio to be the location of a silver mine on a map he published in 1829.

The silver deposits were thought to occur in an area from around the San Saba River southward beyond the Llano River, and eastward to the Colorado River. Because of the rumors of silver and Austin’s map, prospecting occurred throughout the area and treasure hunters abounded, mostly searching in the presidio area. Sporadic searches for Los Almagres continued into the early 20th century with at least one site thought to be the Spanish Colonial site, located in the Riley Mountains just north of Honey Creek.

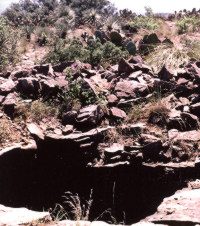

In the 1970s, an area rancher discovered a group of mines on his property along the southern slopes of Packsaddle Mountain, just south of Honey Creek, a short distance southwest of the Llano River and near its confluence with the Colorado River. He asked Christopher Caran, a consulting geologist, to investigate the mines. In 1999, Caran organized a group of geologists and archeologists to do so. Using information from on-site examination and archival resources, two archeological sites were recorded on the property. A third site was recorded on an adjacent property further north on Packsaddle. Field investigation included metal detector surveys and examination of the surface, the interior of shafts, tunnels, open pits, and modified natural caves. Spoil piles were found at all of the excavated features.

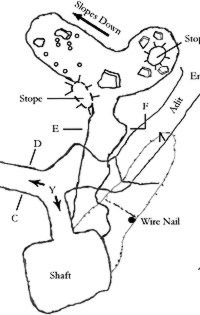

In the largest site, one feature contains a deep shaft with a side tunnel far down inside the shaft. Another feature includes a deep shaft accessed directly from the surface and by a second entrance with a tunnel leading downward to the shaft (see plan and profile maps, above). There are side tunnels at three levels. A third feature consists of a long tunnel and a shorter side tunnel cut into the side of a hill. Pick marks and drill marks were observed near the entrance. Artifacts included cut nails, a broken pick point, and a chisel. A concentration of cut nails at another feature indicates a probable structure. Cut or wire nails were noted in various tunnel walls throughout the site.

The second site contains several excavations, including a shaft and a modified natural fissure, as well as the remains of a brick smelter. The surface of the fissure contains anchor points for a cable-hauling system to transfer ore to the smelter. The third site includes three modified natural caves with excavated side tunnels. A probable gunpowder can was found in one cave.

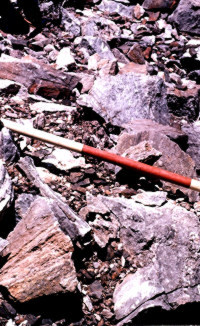

Although few artifacts were available for dating, a number of characteristics in the excavations also were used to suggest approximate time periods for many of the excavations and to determine if any could be Los Almagres. Changes in mining technology were evident, from early hand-excavations using barras and picks, and removal of the rock from the mine manually, to the use of dynamite and removal of the materials by mechanical means. This change also resulted in a difference in the spoil materials: Spanish Colonial miners broke out rock in consistent sizes, which would be carried out, piece by piece, through the shaft Typically the hauling was done by young boys, who could pass more easily through the smaller passages. However, the adults would have had to wield the heavy barras. Later techniques, involving dynamite, resulted in angularly fractured rock pieces in a wide range of sizes. The changes from wrought iron to high-quality steel, and from cut nails to wire nails, provide estimates of the times when the associated excavations occurred.

Another possible means of assessing the age of activity at the mines—or at least the spoils areas—may derive from a lowly organism growing on the rocks: lichen. By correlating the maximum size of lichen on spoils rocks with the average annual growth rates of lichen, an approximate age of the rocks may be determined. For example, by using a conservative average growth rate of .02 cm per year and noting that it has been over 200 years since the time of Los Almagres, the maximum size of lichen on some rocks in spoil areas would be expected by now to be about 13 cm (5 inches). This is, in fact, what is seen on some of the spoil materials. While this particular correlation may be serendipity, it is nonetheless an interesting starting point for a new research approach.

In all, three time periods are indicated in the sites examined: the Spanish Colonial period of the 1700s and early 1800s, the Mexican and Early Anglo period of the middle to late 1800s, and the later Anglo period of the early 1900s. Several features appear to have been worked during two or more of these periods.

English translations of Miranda's journal describing his route to Los Almagres, with reported landscape features along the way, indicates the route most likely led to Packsaddle Mountain and the adjacent Honey Creek. Although archival research, fieldwork, and analysis are still in progress, it appears that at least one or two mine features could be the Spanish Colonial mine Los Almagres. Evidence so far suggests there never were economically important silver deposits in this area.

Credits

Los Alamagres was written by Samuel D. McCulloch with the help of Jan Jackson. The two, along with S. Christopher Caran, are currently writing the report of investigations for the Texas Historical Foundation, which helped underwrite research conducted there. Graphics are by Ron Ralph and Jan Jackson.

Further reading

Caran, S. Christopher

2000 The Lost Spanish Silver Mines of Llano County,

Texas. Texas

Heritage 18 (4)l:9- 35, Texas Historical Foundation, Austin.

Caran, Chris, Mark Helper, and Richard Kyle

2000 Geology and Historical

Mining, Llano Uplift Region, Central Texas. In Guidebook 20, Austin Geological

Society.

Caran, S. Christopher, Joe R. Wallace, and James Stotts

2000 Evidence

of Spanish Colonial Mining, Llano County, Texas. In Geology

and Historical Mining, Llano Uplift Region, Central Texas, by

Chris Caran, Mark Helper, and Richard Kyle, pp. 65-73. Guidebook 20,

Austin Geological Society.