Bering Sinkhole

Bering Sinkhole (41KR241) in northwestern Kerr County is a natural sinkhole that was used as a cemetery by native peoples for over 5,500 years from the latter Early Archaic to the Late Archaic periods. Human remains and burial offerings from the sinkhole provide a glimpse of the health and beliefs of hunting and gathering peoples living in the central Edwards Plateau.

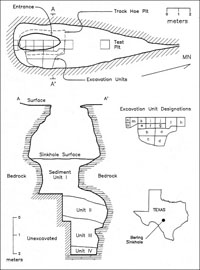

The sinkhole was discovered by accident while brush was being cleared along the property line between two ranches in the central portion of the Edwards Plateau about 20 miles southeast from Junction. Sinkholes are fairly common on the Plateau—they form as solution cavities in porous limestone bedrock. In this case, the landowner found an oval-shaped opening measuring some 7-x-12 feet from which a dead tree protruded. Beneath this was a dark hole that proved to be a vertical shaft filled to within about 10 feet from the surface. To satisfy his curiosity, the landowner used a track hoe (Iarge backhoe) to probe into the fill from the opening above. Animal and human bones and several Indian artifacts were found in the soil removed from the sinkhole, prompting the landowner to contact area universities to find someone who could examine the finds.

As a result, archeologists from the Texas Archeological Research Laboratory conducted hand excavations at Bering Sinkhole between 1987 and 1991. The site materials were analyzed and reported by Leland C. Bement as part of his Ph.D. dissertation at the University of Texas at Austin and later published through the University of Texas Press. Bement undertook a multi-disciplinary analysis of the sinkhole and the materials recovered from within. The human remains from the sinkhole were studied to reconstruct the diet and demographic patterns of the Archaic-era hunter-gatherers who used the sinkhole as a cemetery.

Below its shaft entrance, Bering Sinkhole opens into a somewhat larger chamber (12-x-40 feet) at least 25 feet deep that was two-thirds filled with natural sediment. The sediment contained human remains, animal bones, and artifacts, including apparent grave offerings and tool-making debris that may have washed in from the surface around the sinkhole opening. The human remains were found within various fill layers; most were scattered and did not appear to have been placed within grave pits.

The uppermost fill layer containing human remains lay some 16 feet below the surface. As access into the sinkhole is only possible with the aid of ladders or ropes, it is believed that the deceased were probably lowered or simply dropped into the sinkhole. In some cases, bodies were apparently covered with limestone blocks intentionally dropped into the sinkhole.

Based on the limited excavations, Bement estimated that at least 62 people and possibly upwards of twice that many may have been buried at the site between about 5000 B.C. and A.D. 500 (Early to Late Archaic periods). The deceased ranged in age from infants to adults at least 50 years old. The burials included at least six adult cremations and one adult bundle burial. The gender of the interred individuals seems to have been equally divided between both sexes, based on the remains of 11 males and 11 females recovered from the site.

Most of the individuals buried at Bering Sinkhole were judged to have lived healthy and disease-free lives. Special isotopic analysis of human bone samples revealed that the native peoples represented by the cemetery depended more heavily on carbohydrate-rich plant foods than meat. In other words, gathering provided more of the diet than hunting.

Some of the interments in Bering Sinkhole were accompanied by offerings of utilitarian or personal items such as stone tools as well as ornaments and ritual items such as bone and shell beads, marine shell pendants, bone hair pins, and a freshwater turtle shell possibly used as a hair ornament. Deer antler fragments, some of which were burned, may represent whole antler racks used as ritual offerings similar to those placed over Late Archaic graves at the Olmos Dam site in Bexar County. A cache of 14 large bifaces and one stone drill recovered from the Bering Sinkhole probably represents another type of special ritual offering, estimated to date between 2250 and 650 B.C. Ten dart points found in the sinkhole could represent offerings, but some may have been imbedded within the interred bodies.

Prehistoric cemeteries are relatively rare on the Edwards Plateau in contrast to the coastal plains of southern and southeastern Texas. Bering Sinkhole probably helps us understand why large open cemeteries are not found in the Plateaus and Canyonlands region. Native peoples appear to have used natural sinkholes for burial locations. Based on what is known about the beliefs of native peoples in the American Southwest and Northern Mexico, such natural cavities were probably regarded as symbolic entrances to the underworld. Thus, the bodies were not merely tossed into a convenient hole in the ground; the deceased were ritually placed within a sacred passage to the ancestral world and accompanied by offerings and blessings.

Reference

Bement, Leland C.

1994 Hunter-Gatherer Mortuary Practices during

the Central Texas Archaic. University of Texas Press, Austin.