The Case for Ritual Abandonment of a Jornada Mogollan Pueblo |

A 3-D computer rendering of Madera Quemada Pueblo, based on excavated remains, is shown with Old Coe Lake Playa and the Organ Mountains in the background. Occupied for only a short period of time and then mysteriously abandoned, the 13-room pueblo is exceptionally well preserved and holds a wealth of information for researchers studying architecture, ritual, and economy of puebloan people. Image by Farrah Welch, provided courtesy of Fort Bliss Environmental Division, Geo-Marine, Inc., and the artist. |

|

|

The name, Madera Quemada, refers to the large quantities of burned roof beams and roof support posts found on the floors of several rooms. Species of wood used for the roof supports and beams include Ponderosa pine, Pinyon pine, juniper, and cottonwood. The pine wood was collected from elevations of 7,000 feet or higher in the nearby Organ Mountains and had to be transported several thousand feet in elevation and a distance of several miles across the mountain foothills and around the margins of the playa. The wood species identified among the rooms presents an interesting pattern. Cottonwood, juniper, and mesquite wood was used to construct the roofs of the domestic rooms. These tree species were present around the margins of the playa and the lower elevation foothills of the Organ Mountains, and could be easily harvested and transported to the pueblo. In contrast, most of the wood used to construct Room 4, the large communal room, consisted of Ponderosa and Pinyon pine that had to be harvested at higher elevations and more distant areas in the Organ Mountains. The construction of the communal room at Madera Quemada truly involved a multi-person effort of the inhabitants to harvest and transport these construction timbers. Collections of food preparation tools and workshop artifacts were present on the floors of many rooms. These items provide insights into the technological adaptations of pueblo agriculturalists. Grinding tools were stacked together on the floor of Room 12. Obsidian nodules, waste flakes, and small projectile points were found in the corner of one room. The bases of pottery vessels used as “plates” and paint palettes were common on the floors. Perhaps the most notable finding was the pottery manufacturing workshop in Rooms 6 and 8. Mounds of processed clay, smoothing and scraping tools used to finish clay vessels, and paint grinding palettes and mineral pigments used to decorate the vessels, were recovered from these rooms. In addition, a subfloor pit in Room 8 was filled with prepared pottery temper consisting of crushed volcanic rock from the local mountains. Far-Flung Contacts Although much of the daily lives of the inhabitants centered on food production and food hunting and gathering, the inhabitants of Madera Quemada pueblo participated in a wider social and economic world. Fossilized palm wood from the Gulf Coast region of Mexico and Texas and items of marine shell from the Pacific coast of Mexico and the Gulf of Cortez were found in many of the rooms. Room 4 again proves significant as the majority of shell items were recovered from subfloor pits in this room, indicating that much of the wealth of the community was cached in the communal gathering place. |

|

Items found on room floors, from left to right, bead cache in floor of communal Room 4; turquoise pendant; large selenite uniface. |

|

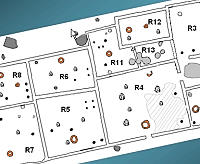

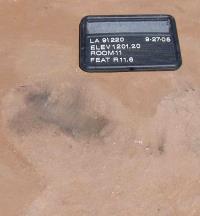

Turquoise beads and pendants were recovered from the floors of rooms and in subfloor pits, some of which may represent “termination offerings” – items intentionally left in place upon abandonment of the pueblo. The source of some of these items may have been the turquoise mines in the Jarilla Mountains, located about 20 miles to the northeast of the pueblo. On the other hand, some of the turquoise may have been mined at more distant locations, such as the Cerrillos source near Santa Fe, New Mexico. The obsidian projectile point found in Room 5 came from the Cow Canyon source in southeastern Arizona and an obsidian core found in the same room came from the Red Hill source in far western New Mexico. The people of Madera Quemada clearly had widespread trade and social networks that stretched across west Texas, southern New Mexico, and southern Arizona, from the Gulf coast to the Pacific. Other unusual items were obtained in local mountains and indicate that the inhabitants of Madera Quemada continued to move across the landscape despite their sedentary pueblo lifestyle. Numerous fossils obtained from limestone deposits in local mountains were found at the pueblo. Mineral pigments such as limonite and hematite were also gathered from outcrops in the mountains. Vesicular basalt obtained from volcanic flows along the Rio Grande valley was used for grinding tools. Items of mica, selenite, and gypsum were brought to the pueblo from areas around White Sands National Monument and Lake Lucero, 30 to 40 miles to the north. There are ethnohistoric accounts from pueblos in the “Rio Abajo” area of the Rio Grande valley and further north of native peoples using sheets of translucent selenite as windows. Whether the sheet of this material found at Madera Quemada was used in a similar fashion is unknown. Puzzling Questions One of the more curious aspects of the excavations at Madera Quemada is that very few plant remains were recovered. This is quite a contrast to most other El Paso phase pueblos, such as Firecracker Pueblo, where hundreds of burned remains of corn, beans, squash, mesquite, cheno-am seeds, and numerous cacti species have been recovered. Evidence of an agricultural economy was present at Madera Quemada in the form of the large subfloor storage pits in Room 2 and the numerous mano and metate grinding tools found in most of the rooms and outside of the room block. Despite the presence of these features and tools, the near absence of charred food remains is one of the most puzzling aspects of the pueblo. Perhaps the inhabitants experienced an episode of severe drought or another cause of subsistence failure? The abandonment of Madera Quemada pueblo appears to have been rather abrupt. It appears that the two westernmost rooms were left unfinished. The walls of these rooms were the thickest and best-preserved at the site, yet no hearth, post holes, or pits were present in the floor and very few artifacts were present. There is some fascinating evidence for ritual abandonment and burning of the pueblo. Feature 11.2 is a pit that cut through the wall separating Rooms 11 and 13. The fact that it cut through the walls shows that it was dug by the prehistoric inhabitants during or immediately after abandonment of the pueblo. The pit was filled with over 250 objects, including fragments of shell jewelry, stone pigment palettes, several grooved quartz crystals, over 40 fossils, and 25 pigment chunks, pieces of selenite (gypsum), minerals, and numerous other items. The analysis and interpretation of all these materials has just begun. Samples of charred organic material, animal bone, and soils, have been sent to specialists for identification of food items. Turquoise, obsidian, and ceramics are being chemically analyzed to determine geological source areas. Analyses of pottery, grinding tools, and chipped stone tools have begun to provide insights into prehistoric technologies of pueblo dwellers. The study of architecture, artifacts, and ritual at Madera Quemada will provide many new insights into the economic, social, and ritual life of pueblo dwellers in west Texas and southern New Mexico. Credits and SourcesThe Madera Quemada exhibit was written by archeologist Myles Miller. TBH editor Susan Dial assisted by Carly Whelan created the exhibit which was developed for the web by Krutie Thakkar and Heather Smith. Photographs were taken by Juan Arias of Geo-Marine, Inc., and are used courtesy of Fort Bliss. Mark Willis of Blanton and Associates took the aerial photographs and composed the 3-D movie showing the excavated site at different angles. Several of the image montages derive from a Power Point presentation by Miller at the 15th Biennial Jornada Mogollon Conference and Spring 2006 CTA Meetings in Austin. The excavation and ongoing study of material culture from Madera Quemada pueblo is being funded and supported by the Conservation Branch of the Environmental Division, Fort Bliss, Texas. Archeologist Tim Graves served as Project Director for excavations. Myles Miller has been professionally involved with the prehistory of the Jornada Mogollon and Trans-Pecos regions since returning to his home town of El Paso upon completion of graduate school in 1983. He first became interested in the region during grade school while accompanying members of the El Paso Archaeological Society during trips to prehistoric sites across northern Chihuahua. For the past 25 years he has conducted research and cultural resources management projects throughout the region and has participated in numerous excavations of prehistoric villages and hunter-gatherer campsites and historic Native American settlements in west Texas, southern New Mexico, and southeastern Arizona. He presently serves as a Principal Investigator with Geo-Marine, Inc. and supervises archeological consulting work performed at Fort Bliss. |

|

Print SourcesBrook, V. R. 1967 The Sarge Site: An El Paso Phase Ruin. The Artifact (5)2. El Paso Archaeological Society. Foster, M. S., and R. J. Bradley Foster, M. S., R. J. Bradley, and C. Williams Gerald, R. E. (editor) Lehmer, D. J. Lowry, C. Miller, Myles R. and Tim B. Graves Moore, G.E. O’Laughlin, T.C. Scarborough, V. L.

LinksMadera Quemada Project Wins Award Firecracker Pueblo |