Sotol

Dasylirion texanum

Agavaceae Family

This spiny evergreen plant was an important food staple for the native peoples in the Lower Pecos Canyonlands and adjacent areas of the western and southern Edwards Plateau. Native peoples also made use several other sotol species that can be found to the west across much of the Chihuahuan Desert in northern Mexico and the southern part of the American Southwest. The pulpy central stems or "hearts" of sotol plants were baked and then pounded and formed into chewy patties which could be dried and stored. This carbohydrate food source was probably a mainstay in areas where sotol grew in abundance.

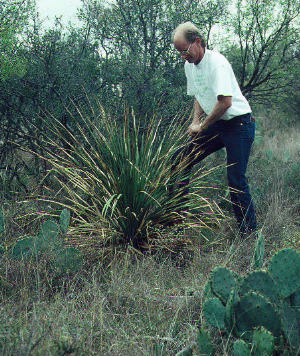

Sotol is a evergreen rosette plant, with long spine-clad leaves that attach in a series of circular tiers around a shortened, central stem. Although sotol is sometimes called a "cactus" or an "agave," it is neither. Some botanists today classify it a member of the Nolinaceae family, like beargrass, while others place sotol in the Agavaceae family (e.g., Powell 1998), along with the true agaves such as lechuguilla. The tough fibers from sotol leaves were used for making mats and twine and its woody flower stalk was valued as a straight, lightweight wood useful for many tasks. Sotol seeds are also edible, and have been recovered from coprolites (preserved human feces) analyzed from dry caves in the Lower Pecos archeological region.

Weaving and basketry. Sotol leaves are an ideal material for weaving mats, trays, burden baskets, tumplines, and general purpose baskets (Andrews and Advasio 1980; McGregor 1992). Preparation of the leaves for weaving is simple. The leaf is either utilized whole, or split into narrow strips. In some cases, the marginal teeth (spines) are removed before the leaf is woven into a mat. In other cases the leaves with the marginal teeth intact are woven into the basket or mat. In a comprehensive study on basketry of the region, McGregor (1992) identified sotol in mat and basket fragments. Often sotol was woven into baskets with other materials, including yucca fibers or strips of yucca leaves, agave fibers, or grass fibers.

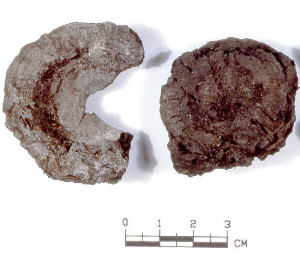

Food. The plant's central stem is very fleshy or pulpy, and serves as a storage organ, containing both moisture and carbohydrates. The central stem, often referred to as the “heart,” is edible, but only after it is baked in an earth oven for 36-48 hours. The very long cooking time is needed to break down indigestible long-chain carbohydrates and poisonous compounds, mostly saponins, which are a combination of a sapogenin, a steroid compound, and a sugar, usually glucose. The heat and steam generated by an earth oven, however, breaks down complex carbohydrates, splits the sugars from the steroidal compounds, breaks down the compounds, and leaves the pulpy central stem edible. Usually the cooked, fleshy pulp was pounded into thin patties and sun-dried. If kept dry, baked sotol patties can remain edible for months: chewy, but sweet and nutritious. It tastes like nutty molasses syrup.

Most researchers associate agave use throughout the Chihuahuan and Sonoran Deserts of northern Mexico and the adjacent American Southwest (including west Texas) with earth oven processing. It is, however, increasingly evident that both sotol and yucca were utilized as important food sources in the Edwards Plateau region. For example, San Angelo (or narrow-leaf) yucca [Yucca reverchonii], a plant with an inedible fruit, was identified from deposits at Baker Cave (Brown 1991). Both yucca and stool have been identified in abundance from Hinds Cave (Dering 1999). When baked in an earth oven the central stem of San Angelo and other related yuccas is edible and can be prepared much like sotol.

It is very likely that sotol and yucca were among the main food resources that were routinely cooked at many archeological sites in the western and southern Plateaus and Canyonlands. Over time, this process results in the accumulation of “burned rock middens,” the highly visible, common, and easily identified prehistoric site feature in the region. Archeologists have recovered charred sotol and/or yucca fragments (leaf sections) from burned rock midden sites on the Edwards Plateau, such as the Honey Creek site. Unfortunately, it is almost impossible for paleobotanists (specialists who identify plant remains from archeological sites) to tell the difference between sotol and yucca from small charred fragments. Therefore, most of what we know about sotol and yucca use comes from the dry caves of the Lower Pecos area.

One fascinating account of sotol baking comes from The Life of F. M. Buckelew: The Indian Captive, As Related by Himself (1925). Buckelew was captured as a 14-year-old boy by Lipan Apaches in 1866 near what is today Utopia, Texas on the Sabinal River. He lived with the Lipan for about a year in the western Edwards Plateau and further west in the Big Bend area before he escaped. His account describes in detail the preparation of the sotol "bulb" or central stem, in earth ovens. He describes large quantities of the sotol being cooked in a "kiln" covered with earth to make it airtight. The heated rock, he said, cooked the bulbs, which were then made into "bread."

References:

Andrews, Rhonda L. and James M. Adovasio

1980 Perishable Industries from Hinds Cave, Val Verde County, Texas. Ethnology Monographs Number 5. Department of Anthropology, University of Pittsburgh. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

Bell, Willis H. and Edward F. Castetter

1941 The Utilization of Yucca, Sotol, and Beargrass by the Aborigines in the American Southwest. The University of New Mexico Bulletin 372, Biological Series 5(5), Albuquerque, New Mexico.

Brown, Kenneth M.

1988 Some Annotated Excerpts from Alonso de Leon's History of Nuevo Leon. La Tierra 15(2):5-20.

1991 Prehistoric Economics at Baker Cave: A Plan for Research. In Papers on Lower Pecos Prehistory, edited by S. A. Turpin, pp. 87-140. Studies in Archaeology 8. Texas Archaeological Research Laboratory, University of Texas at Austin, Austin, Texas.

Dennis, T. S. and T. S. Dennis

1925 Life of F. M. Buckelew. Hunter’s Printing House, Bandera, Texas. [1977 reprint,The Garland Library of Narrative of North American Indian Captivities, vol. 107, W. E. Washburn, general editor. Garland Publishing, Inc., New York. ]

Dering, J. Philip

1999 Earth-Oven Plant Processing in Archaic Period Economies: An Example from a Semi-Arid Savannah in South-Central North America. American Antiquity 64(4):659-674.

McGregor, Roberta

1992 Prehistoric Basketry of the Lower Pecos, Texas. Monographs in World Archaeology 6. Prehistory Press. Madison, Wisconsin.

![]()