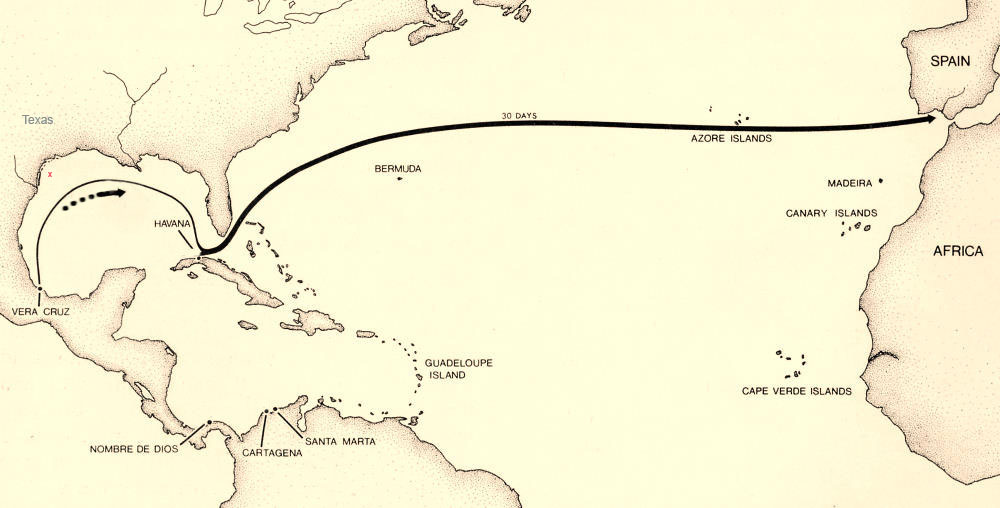

On April 9, 1554, four vessels of the Spanish Plate Fleet set sail from Veracruz, Mexico, port of San Juan de Ulúa, on their homebound voyage to Spain, where anxious merchants awaited the valuable cargo on board. Spain regularly employed merchant convoys to transport silver and other commodities from its New World territories for a period of over 200 years, during the 16th to 18th centuries. By 1537, these would be protected by armed warships—a system that was formalized in 1564 as the New Spain (Mexico) and Terre Firme (South America) fleets. These convoys are also known as the Spanish Plate Fleets with "plate" derived from plata, the Spanish term for silver.

The fleet that departed from San Juan de Ulúa in April 1554 included four ships—the San Andrés, San Esteban, Espíritu Santo, and Santa María de Yciar—and carried more than 400 people. Among them were prisoners, old conquistadors, merchants, and wealthy citizens returning home to Spain. En route the convoy was to stop off in La Havana, Cuba. Of the four ships, only the San Andrés was to reach Havana. The remainder met a disastrous fate off the Texas coast. The story of the shipwrecks and the harrowing trials of the survivors provides one of the earliest and most interesting accounts in Texas history.

The convoy was halfway to Havana on April 29, 1554, when a storm hit. Twenty days into an 18-20-day journey, the fleet was well behind schedule and it is believed the vessels deliberately altered their route to travel close to the coast to take advantage of the faster currents. Unfortunately, this also placed them at risk of encountering dangerous storm waves and being blown ashore. Such was the fate of the convoy, as San Esteban, Espíritu Santo, and Santa María de Yciar ran aground on the sandbars off Padre Island, about 50 miles south of Corpus Christi Bay. More than 300 people died during the tragic event, which has become known as "The Wreck of the Three Hundred."

The three ships wrecked within 2½ miles of each other, and it is believed that their crews and passengers banded together for comfort and safety. Master of San Esteban, Francisco del Huerto, salvaged a boat and sailed for Veracruz with a few seamen. Other survivors from the ship started walking southward, believing a Spanish outpost was within only a few days walk. Their assumption proved wrong. Of this group, only one survivor made it to Tampico, which was actually 300 miles away.

Local tribes picked off the survivors during their torturous journey. At first, they offered some of the injured survivors fish to eat. Once at the campsite, they attacked them. Other Spaniards stripped off their garments along the trail, thinking the Indians wanted their clothing. Without even that meager protection, the group faced even greater hardships—mosquitoes and hot sands. Many traveled with wounds from Indian arrows, including Fray Marcos de Mena, who was shot seven times. His companions, thinking death was imminent, buried him in the sand, leaving only his head exposed. Revived by the warmth of the sand, he crawled from his "grave" and made his way along the coast. Friendly natives helped him make his way to Panuco. After a brief respite in Panuco, Mena, the last survivor, would continue to Tampico.

Captain Huerto reached Veracruz safely, and there he told his story to Spanish officials. On June 6, a rescue mission, led by Angel de Villafañe, set out by land to search for survivors. Meanwhile, a salvage expedition was organized and outfitted in Veracruz. On July 15, 1554, six salvage vessels under Captain García de Escalante Alvarado left Veracruz for the site of the wrecks. The ships had carried a valuable cargo from Spain to Mexico—resins, sugar, wood, cowhides and cochineal (insects from which a red dye could be produced) valued at $9.8 million in Spanish currency; gold bars and silver bullion bound for the coffers of Charles V; and reales from trade in the New World. In the face of this lost wealth, the ships demanded salvage efforts.

Spanish salvage operations began on July 21, 1554 at San Esteban. Villafañe located Espiritu Santo and commenced its salvage more than a week later on July 29. According to Spanish accounts, Villafañe's divers found a trunk belong to Pedro Milanes, a man they knew. Milanes' possessions included a black satin tunic with blue velvet sash, a cape of sailcloth, a pair of shoes, three small silver disks, and 100 pesos in coin. Alvarado found Santa María de Yciar on August 20 with its cargo scattered outside and within the wrecked hull. A storm sank the salvage vessel, but uncovered seven more boxes of cargo.

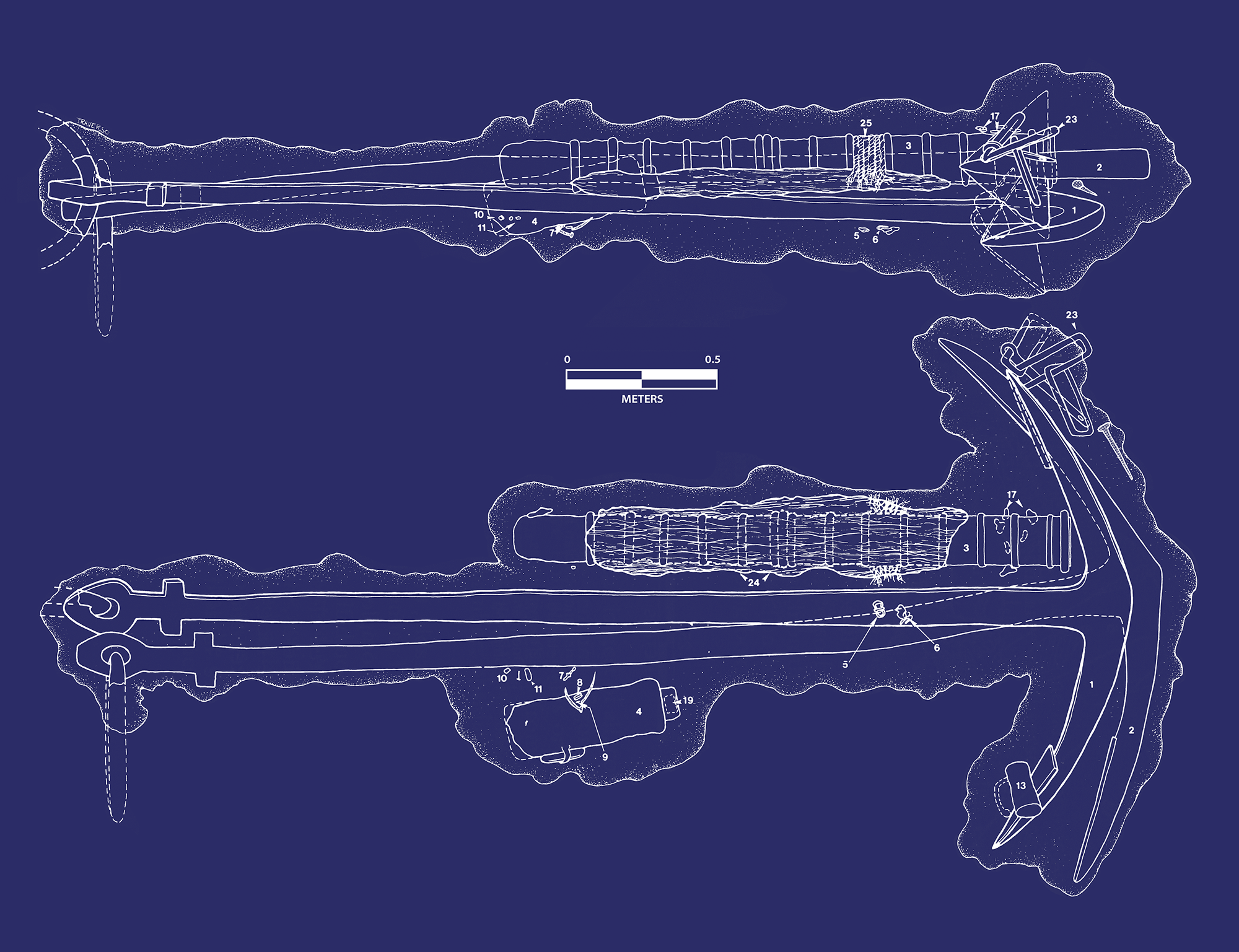

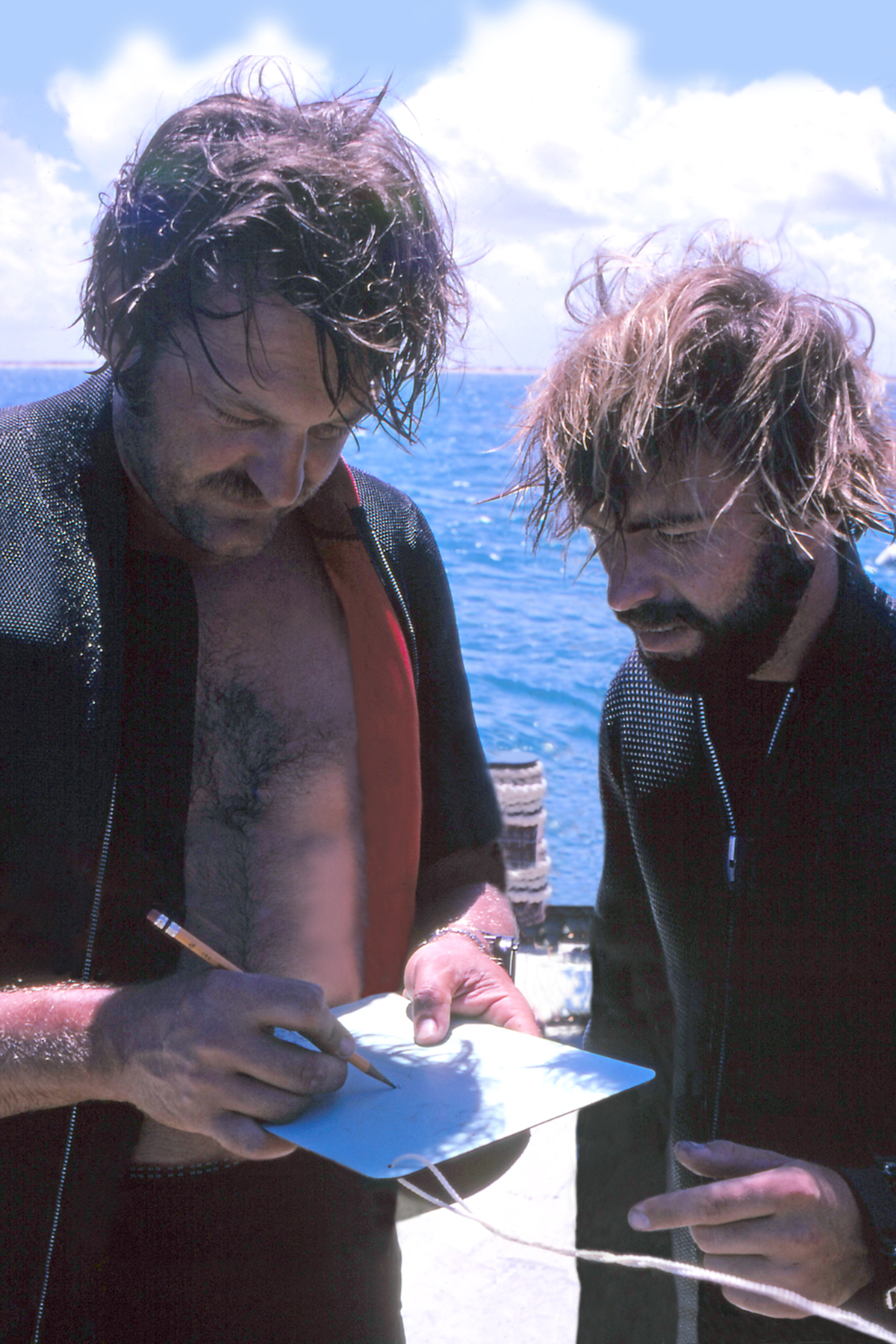

The sunken vessels were rediscovered by philanthropist and explorer Vida Lee Connor in 1964 while conducting an aerial reconnaissance for offshore reefs. After further investigation, she announced her discovery to the media in 1966. Connor revisited and dived the sites during the mid-1960s until her efforts were interrupted by modern salvors. One day while returning to revisit the sites she witnessed artifacts being removed by draglining—Platoro, Inc., a private enterprise from Indiana, began salvaging artifacts from Espíritu Santo in 1967. This commercial salvage effort by a private enterprise alarmed Texas officials because they felt that the recovered artifacts were rightfully the property of the citizens of Texas. They were also concerned that significant historical and archeological data were being destroyed in this unscientific process. Their position was strengthened considerably with the adoption in 1969 of the Texas Antiquities Code, a major protective act directly related to the Platoro controversy. Under this Code, the Texas Antiquities Committee (now Texas Historical Commission [THC]) conducted scientific excavation and recovery of San Esteban from 1972–1975. The shipwreck has considerable significance; it is among the oldest scientifically recovered shipwreck sites in the Western Hemisphere.

The Texas Archeological Research Laboratory at the University of Texas at Austin was given temporary custody of a large portion of the recovered materials in order that they be properly conserved and catalogued. Under the direction of Donny Hamilton, more than 7,000 artifacts were processed and classified during the project. Layers of encrustation had to be painstakingly removed from metal artifacts, many of which had formed into large concretions. X-rays were taken to discern what lay inside these masses. Analysis and identification of many of the artifacts was successfully completed. In 1984, the Corpus Christi Museum of Science and History was named repository of the San Esteban collection. Two years later, the Museum was named repository for the Platoro, Keenan, and Purvis Collections—artifacts the salvors recovered from Espíritu Santo.

Among the collections are weaponry, coins, supplies, personal items, and navigational devices including two astrolabes. One of the astrolabes is dated 1545 and is one of the oldest mariner's astrolabes recovered from an underwater archeological site.

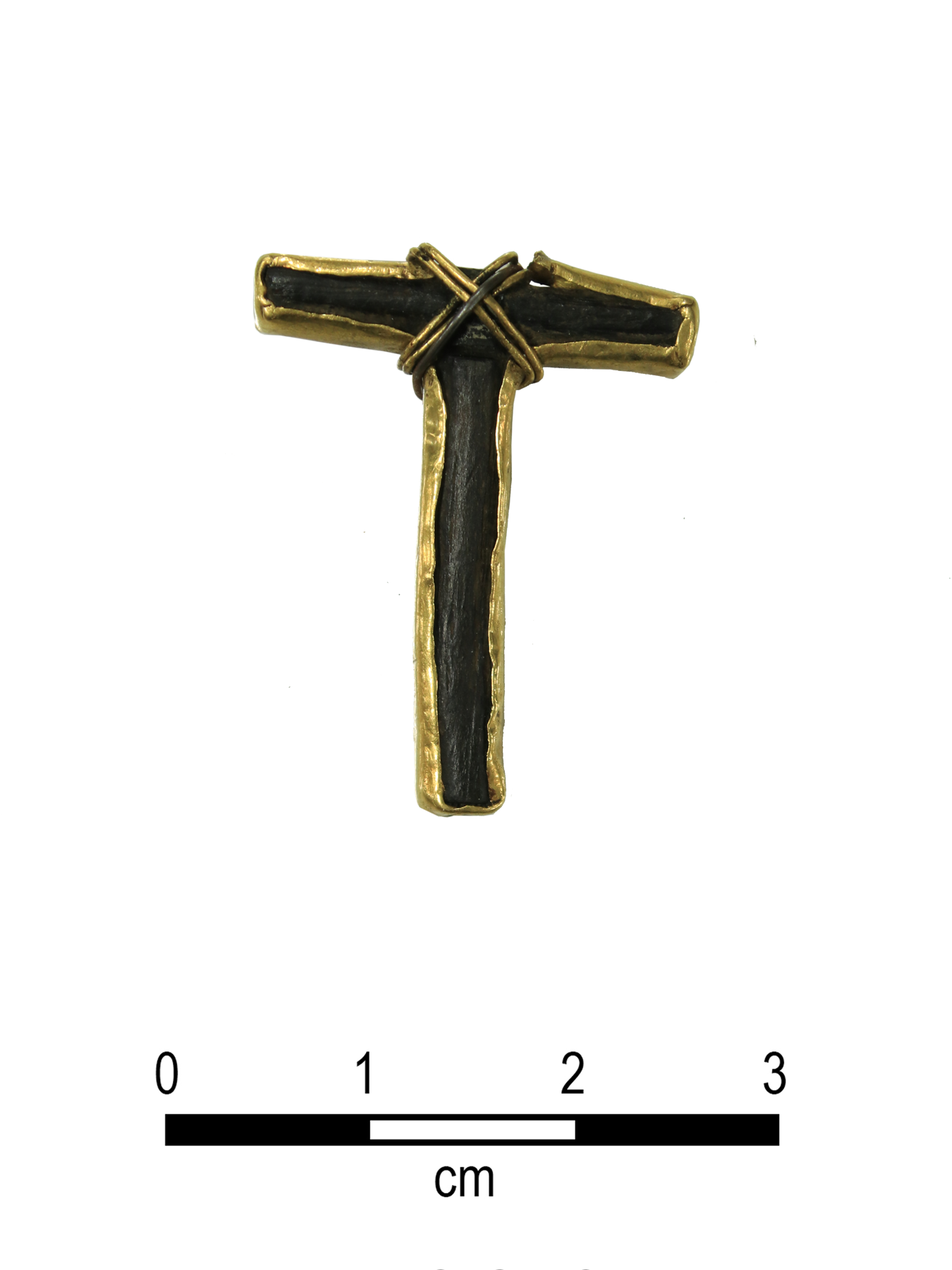

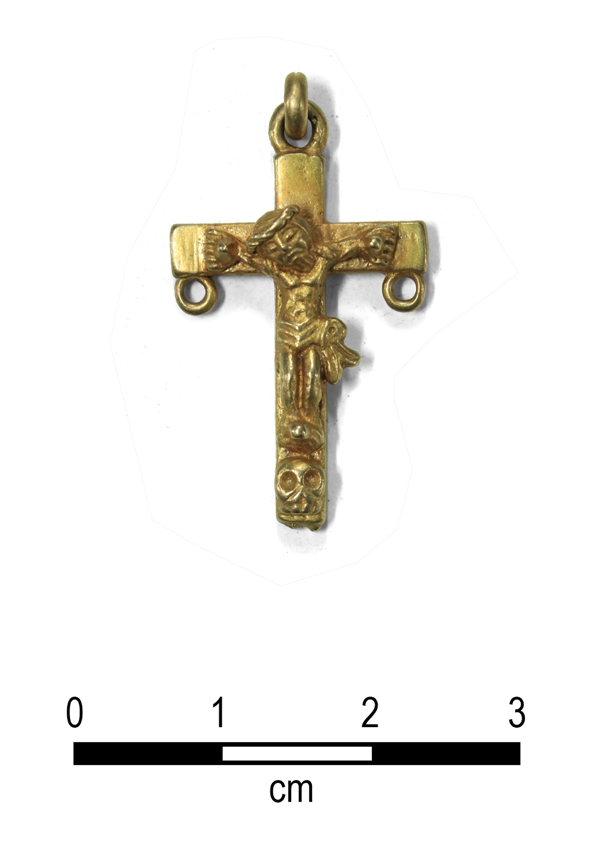

Then there were personal items carried by passengers, souvenirs and necessities of 16th-century life. Straight pins and silver thimbles, a crossbow and an obsidian blade, a gold crucifix and silver reales reflect the styles and values of passengers and mariners.

Additional archeological investigations of the 1554 Spanish Plate Fleet by the THC occurred in 1977 and later by National Park Service (NPS), with the THC, during the mid-1980s. Searches for the third vessel, Santa María de Yciar, were also conducted in the late 1980s and early 1990s by cultural resource management firms for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers in advance of modifications to Mansfield Cut. It had long been rumored this vessel had been destroyed by the creation of the channel—an account that has not been substantiated by archeological or documentary evidence. New investigations of the 1554 Spanish Plate Fleet wrecks conducted by NPS in partnership with the THC commenced in 2020.

The wreck sites and the camp site of the salvors that worked on the recovery effort in 1554 are under protection of the Padre Island National Seashore and the State of Texas. They are within the Mansfield Cut Underwater Archeological District, listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1974. Shipwreck!, an exhibit based on the artifacts recovered, opened at the Corpus Christi Museum in 1990 and is maintained as a permanent exhibit for visitors.

Analysis of the curated collections continues to provide insight and new avenues of research. X-ray fluorescence sourced the obsidian blades to two distinct sources in the Sierra de las Navajas in the basin of Mexico. Archeologists are exploring how they were used by passengers. Ongoing studies are looking into the origins of the ballast to help identify it when it is encountered inshore, and stable isotope analysis of the faunal remains is helping to better understand Spanish colonial supply and animal husbandry.

Over fifty years after their rediscovery and excavation, the 1554 shipwrecks remain important and exciting archeological discoveries. Further collections analysis and field investigations will continue to enrich our understanding of Spanish colonialism in the Americas for at least the next fifty.

Kids' Activity

Kids of all ages can visit the excavation of the wreck of the San Esteban with a Dr. Dirt coloring sheet!

Credits & Sources

Contributed by Robert Drolet and Rick Stryker, Corpus Christi Museum of Science and History. Revised by Amy Borgens and Bradford Jones, Texas Historical Commission in 2024.

- 1978 The Nautical Archeology of Padre Island. Academic Press, NY.

- 2022 The 1554 Spanish Plate Fleets of Padre Island—the Semicentennial Anniversary of the THC’s Excavations. Medallion.

- 2022 The 1554 Spanish Plate Fleet—its Cultural Heritage and Legacy. Sea History.

- 2022 The 1554 Spanish Plate Fleet: The Texas Historical Commission’s First Underwater Archeology Project.

- 1969 Treasures Recovered Off Padre Island. J.A. Baldwin Co. Collection of the Texas Historical Commission, Marine Archeology Program.

- 1969 Ancient Galleon Sails Again. J.A. Baldwin Co. Collection of the Texas Historical Commission, Marine Archeology Program.

- 1977 Treasure, People, Ships, and Dreams: A Spanish Shipwreck on the Texas Coast. Texas Antiquities Committee and The Institute of Texan Cultures, Austin and San Antonio, TX.

- 1979 Documentary Sources for the Wreck of the New Spain Fleet of 1554. Texas Antiquities Committee Publication 8, Austin, TX.

- 1976 Texas Legacy from the Gulf: A Report on Sixteenth Century Shipwreck Materials from the Texas Tidelands. Texas Memorial Museum Publication 2, Misc. Papers 5, and the Texas Antiquities Committee, Austin, TX.