Black Hill Mound

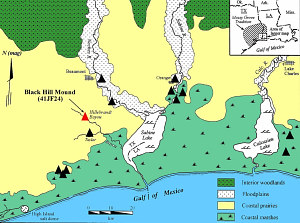

Black Hill Mound (41JF24) is a short distance south of the city of Beaumont in the far southeast corner of coastal Texas. The site is a small but prominent dome-shaped earthen mound about 75 to 90 feet in diameter and some 3 to 6 feet high set in otherwise level terrain. Surrounded in all directions by a pale yellowish brown soil and sub-soil derived from the Pleistocene Beaumont Formation, the mound itself is comprised of very dark colored heavily organic sediment and thus the name "Black Hill." This site remains an intriguing Texas archeological location despite having been significantly damaged over the past century as a victim of random digging for "treasure" and, later, for Indian artifacts.

One of the enduring myths in southeast Texas folklore is about buried treasure. Mounded locations or those with other distinctive physical features occasionally became of interest to treasure hunters, as did Black Hill in the early 20th century. While no treasure ever was found, the hole that was excavated brought to the surface Indian artifacts confirming the mound's identity as an archeological site.

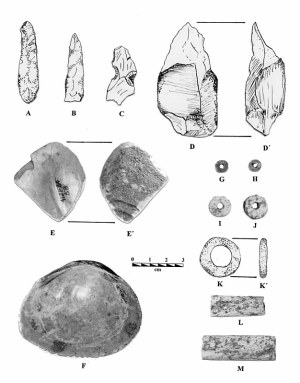

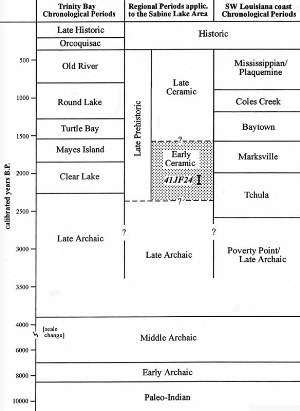

Later, in the 1960s, when the mound still was private property, local artifact collectors digging in the site found several human skeletons as well as prehistoric earthenware, subsequently recognized as diagnostic early pottery, and Archaic stone tools. Because of this, and after becoming public property, the site was inspected and re-evaluated in 2003 under terms of a State of Texas Antiquities Permit. The purpose was to see if additional investigations could be pursued there that would contribute to a study of early ceramic sites in the Sabine Lake area being undertaken by archeologist Lawrence Aten and Texas Historical Commission Archeological Steward Charles Bollich.

They found that, while the local artifact collectors had removed the center of the mound structure and there were many animal burrows creating disturbances throughout the site, these impacts and damage appeared not to ruin all remaining research value at the site. The edge and thickness of Black Hill Mound remained partially intact and some adjacent areas of midden were intact as well. A topographic base map of some of the site as it looked in 1963 was found that showed the location of some of the human skeletons that had been removed and later on turned over to the University of Texas. And finally, native pottery collections made forty years ago and a very helpful student report prepared on the lithic artifacts became available to augment data from the 2003 field investigation.

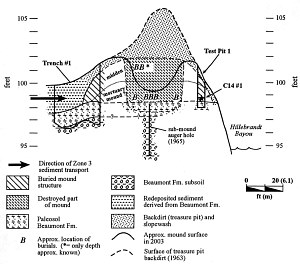

These observations seemed to confirm the potential for Black Hill Mound to expand understanding of early ceramic, and possibly of Archaic, cultures in the Sabine Lake region and made it seem worthwhile to take another look at this site. This was done in three parts: first, a new concrete survey benchmark was installed and the limited topographic map made in 1963 was expanded to record a wider range of features at the site; second, a small stratigraphic test was excavated on the periphery of the site which turned up stratified evidence of an Archaic period occupation and materials on which to obtain radiocarbon dates; and third, because the first two activities yielded positive results, a narrow backhoe trench was excavated beginning at the edge of, and extending 25 feet away from, the mound. In the sidewalls of this trench it was possible to see and record subtle changes in soil layers that appear to document the progressive construction of the mound and its relation to the surrounding landscape.

So what was learned about Black Hill Mound? If we follow the progress of the 2003 investigation, the key features of the mound can be recognized. The site is situated on the middle reaches of the now-abandoned channel of Hillebrandt Bayou which was home to many aquatic resources – especially fish and mollusks (clams). This channel generally followed the lowlands between Pleistocene meander belt ridges in central Jefferson County. These lowlands are typically poorly drained fluvial woodlands including numerous water-tolerant trees and shrubs. The nearby meander belt ridges are upland prairies dotted with small, intermittent lakes. For Native Americans living off the land, the Black Hill locality was accessible to a variety of food and material resources as well as to travel routes by land and water through and beyond the Sabine Lake area.

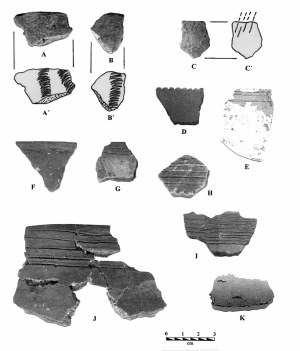

As mentioned, the Indian earthenware collection ultimately came to the attention of Bollich who recognized immediately that the collection included at least some decorated sherds with an affinity to the early ceramic Tchefuncte culture of south Louisiana where larger but structurally similar dome-shaped mortuary mounds have also been found. Once this potential association was recognized attention was devoted to better understanding the structure of Black Hill: was it a simple midden accumulation or was it a structure built to house the dead or to otherwise signify important information – such as territoriality – to inhabitants of the region; or was it all or none of the above?

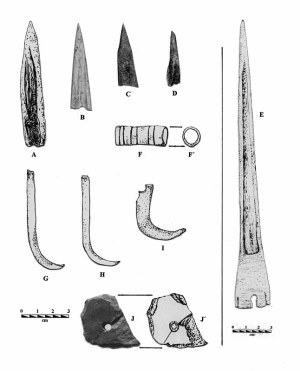

Because Black Hill had suffered much damage from a variety of sources, we did not wish to dig more than absolutely necessary to gain a better idea of what stories this site could still tell. While expanded topographic surveying of the mound locality was underway, a small (1-x-1 meter) stratigraphic test was excavated into the mound's periphery and its contents water screened to improve specimen recovery. This test encountered ceramic and other artifacts in its upper part that appeared to date to the early ceramic – tentatively called the "Orange Period" in the Sabine Lake area and dated to approximately 2500 to 2000 years ago. Apparently the 1960s diggers found three human burials (one adult and two infants) in this upper layer.

In the middle depths of the test excavation were artifacts typical of Middle and Late Archaic cultures. Two radiocarbon dates were run on shell and bone from the lower part of this Archaic zone yielding successive ages of about 6000 and 5350 years ago, or well within the time range of the Middle Archaic Period (about 7000 to 4000 years ago). This appears to be the layer in which the 1960s diggers found five human interments (two adults and three sub-adults). It is unknown whether these burials were interred by Archaic people or whether, as seems more likely, early ceramic people dug graves down into the old Archaic midden deposit before accumulating their own mound or midden deposit. Finally, the lower layer found in the test excavation was transitional from the Pleistocene sediments underlying the mound and was not of archeological interest.

After learning from the small test excavation that there were intact Archaic and early ceramic deposits in the periphery of the mound, it seemed fruitful to push ahead and excavate a short profile trench with a small backhoe to obtain a better record of the apparent structure of this mound. At the edge of the mound a trench 3 to 4 feet deep was dug extending perpendicularly out from the apparent mound's edge for 25 feet. This revealed a structure consistent with that from the small excavation. At the very bottom of the profile under the mound was the Pleistocene Beaumont Formation. Above this was the fossil soil zone once developed on top of the Beaumont, and both of these layers went straight under the mound deposits. Above the fossil Beaumont soil zone were found two layers corresponding to the upper two layers also seen in the small stratigraphic test with a thin layer of weathered material above the early ceramic zone, and above that another thin layer of debris from the treasure hunter's pit. The final interesting feature in the profile trench is that sediments eroding down slope from the nearest meander belt ridge were gradually overwhelming the mound. Over time a thickness of about two feet of eroded Beaumont Formation sediment was accumulating along the Hillebrandt Bayou and around the Black Hill Mound.

When extending the topographic map outward beyond the mound it was discovered that there were a series of low relief ridges and swales surrounding the site. It now appears that these were formed by the down slope transport of eroded Beaumont Formation sediment from meander belt ridges, perhaps in episodes; i.e., high rates of transport – wet periods – corresponding to ridges, and low rates – dry periods –corresponding to swales. These eroded sediments have accumulated to a thickness of about two feet at the base of the mound. So, two thousand years ago, at the end of the Orange Period (early ceramic) the Black Hill Mound must have risen prominently on the level coastal terrain to a height of about five feet and have served as a noticeable landmark, possibly as a territorial boundary.

The combined evidence from 1960s observations and the 2003 investigations suggests that the mound was probably purposefully constructed in two separate stages. First it was a low burial mound, that was later capped with dark organic-rich habitation or midden layer. Whether the upper black matrix and its occupational debris were formed in place or were dug from a nearby (and as yet unlocated) midden location and then transported to the site to build up the mound is not known. However, given the distinct mound boundary, circular mound plan, and the placement of mortuary in the central area of the mound, Black Hill does not simply represent a midden mound.

It must be noted that for many years Black Hill was believed to have been a pimple mound of natural origin. In recent years several such features in the region have been found to contain archeological remains within their aggradational deposits. But at Black Hill this seems unlikely now. Pimple mounds in this region are associated with meander belt ridges and where they occur they are very close to each other and are present in large numbers. This is unlike the Black Hill locality where the site is the only mound at present and no others are evident in the adjacent area either on the ground or on aerial photographs of the locality. Despite this, local lore has it that one or two other apparent burial mounds similar to Black Hill once existed along Hillebrandt Bayou or Willow Marsh Bayou but their locations are presently unknown.

The range of artifacts and animal bones indicates the upper deposit at Black Hill was used for general habitation. But the fact that this evidence occurs directly above the earlier mortuary location suggests the habitation was not simply coincidental. The concentrations of burials rather convincingly shows that Black Hill was a ceremonial mound, possibly what has been called a "power place" by Louisiana archeologist Jon Gibson. At such landscape features, sacred and secular activities occurred periodically in same location, but archeological evidence of these activities is often mixed together. Put another way, in the southeastern Indian cosmos such places were sometimes viewed as portals to supernatural realms. Whatever the meaning of Black Hill in the local belief system, the mortuary layer below and the habitation debris above indicates that mound ceremonialism, possibly including feasting and/or periodic visitation to this location, was a part of those beliefs.

Black Hill fits within the larger Mossy Grave cultural pattern of southeast Texas and southwestern Louisiana. Although it calls to mind the Lafayette mounds of the Tchefuncte culture in Louisiana, Black Hill Mound is much smaller and may not share close structural and functional similarities. Such possibilities remain to be investigated.

Black Hill Mound also illustrates the continuing value of damaged archeological sites. Preservation or investigation should not necessarily be reserved only for the pristine, but as well for the battered site that has suffered at the hands of vandals, construction, rising sea level, or other circumstances, but which, if searched for, may be found to retain a host of important, "hidden" values.

Contributed by Lawrence E. Aten and Charles N. Bollich.

Sources

Aten, Lawrence E. and Charles N. Bollich

2004 Archeological Reconnaissance at Black Hill Mound (41JF24), Jefferson County, Texas. Research report in fulfillment of Texas Antiquities Committee Archeology Permit No. 2902, Texas Historical Commission, Austin.

Gibson, Jon L.

2001 The Ancient Mounds of Poverty Point: Place of Rings. University Press of Florida, Gainsville.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|