Texas Beyond History

Site Map

June 2024

|

|

On a cold winter day in 1686, the Belle, flagship of the French explorer La Salle, hit a sandbar in Matagorda Bay, the victim of bad luck and a sudden violent storm. The Belle was part of a four-ship expedition led La Salle. The explorer had hoped to establish a trading port at the mouth of the Mississippi River (today, that would be at the city of New Orleans). There the French could have traded with the local Indians and sent furs and other items back to France. More importantly, the settlement would have given the French an advantage over the Spanish, who had already claimed vast tracts of land in the New World for Spain. And there were Spanish gold mines that La Salle had heard of, as well. La Salle hoped to launch an invasion of New Spain from his Mississippi port. La Salle Misses the MississippiLa Salle had grand dreams, but here's what happened. The expedition first suffered a pirate attack near Petit Grove in the West Indies, with the pirates taking one of La Salle's ships. Poor navigation and bad leadership marred the remainder of the expedition. Sailors of the 17th century had only crude instruments to steer by and even less reliable maps. In February, 1685, La Salle’s remaining three ships landed on the Texas coast. They had missed the mouth of the Mississippi and were almost 400 miles west of their intended destination! Bad luck continued. La Salle's attempts to find the Mississippi River failed. Then the Aimable, the largest ship carrying most of his supplies, sunk in Matagorda Bay. The settlers traveling with La Salle were stranded and miserable on the beach. To provide temporary shelter and protection from the local Karankawa Indians, the small settlement of Fort St. Louis was established on the banks of a creek above the head of Lavaca Bay. The expedition was further weakened, however, when a group of unhappy colonists, soldiers, and crew decided to leave and return to France on La Salle’s naval vessel, Joly. Meanwhile, La Salle kept widening the search for the Mississippi River, leaving a small group of settlers at Fort Saint Louis and a few crewmen on the last remaining ship, the Belle. Water, Water All AroundOn board La Belle, supplies begin to run low. The crew was dying of thirst, and the ship's best sailors had been killed by the Karankawa in a failed attempt to go ashore to get water. Even though they were only about a quarter of a mile from shore, the sailors could not travel to land without boats or rafts. Most 17th-century European sailors did not know how to swim, even though they traveled over the deepest oceans! So they stayed on board, waited, and suffered. There was water all around them, but none they could drink! On a blustery cold day, with fierce winds pounding the small vessel, the ship's pilot pulled anchor to sail across Matagorda Bay to get help—violating La Salle's orders. In short order, he lost control of the ship. Dragging its anchor, the ship was blown backwards until it smashed into a sandbar. As dawn broke, the crew of La Belle knew they were in trouble. The ship would never move again. The aft was driven firmly into the sandbar, and the front part (bow) of the boat was starting to sink. The crew was trapped and they did not have enough to eat or drink. Sinking Ship, Failing DreamsIn desperation, several of the men made a crude raft of crates and barrels tied together with rope and wire. They set out for shore to get supplies, but the raft capsized. Many or all in this group drowned. Now there were just a few left on board. The captain finished off several kegs of brandy and would not leave, even though the remaining sailors made another raft and set off for shore. Meanwhile, another man lay in the bow of the boat. Perhaps he, too, had drunk too much brandy and passed out. Perhaps he was sick or already dead when La Belle ran aground. Slowly, over several months time, the ship disappeared beneath the muddy waters if the bay. In a final twist of bad fortune, La Salle himself was murdered at the hand of one of his own men, an event which led the Karankawa to attack Fort Saint Louis and kill most of the remaining French settlers. A Spanish expedition, searching for the French men, found the remains of the fort, and the bodies of several of the settlers. The French threat on Texas' shores had passed. La Salle's dream had ended. For 310 years, the Belle remained mired in the mud, untouched but not forgotten. Historians and archeologists knew it was somewhere in Matagorda Bay, but they could not pinpoint the exact spot. In 1995, after years of unsuccessful searching, Texas State Marine Archeologist J. Barto Arnold of the Texas Historical Commission finally found the prize. Working with an underwater scanning machine (called a magnetometer), a crew of divers began finding metal objects beneath the muddy bay waters. Finally, they brought up a brass cannon, an elaborately decorated gun that had the mark of Louis XIV, confirming the age and identity of the wreck. It was the French ship, La Belle! But properly excavating the shipwreck would require one of the most extraordinary engineering feats ever attempted in an archeological excavation in Texas or anywhere else in the world. At a cost of over $1.5 million, a stout double-walled cofferdam was built around the sunken ship in 1996. This allowed archeologists from the Texas Historical Commission to pump out the wreck site and excavate the Belle almost as if they were on dry land. An Amazing ExcavationThe amazing excavation yielded equally astonishing results: gooey gray mud had encased the Belle and sealed its contents off from decay. Most of the ship's stores—wooden boxes jammed with trade goods, casks lined with muskets, miles of woven rope, cannons, dishes, and more—were found in remarkably good condition. Here, for the first time, was an intact 17th-century French colonizing kit containing everything needed to establish a trading post in the New World. Even the ship's hull and timbers were still intact, water-logged and fragile, but still looking very much like they did when La Salle last saw them. The timbers still bore the original numbers scrawled into each piece to aid the ship's builders in assembling the Belle. In the bow section of the ship, archeologists uncovered a skeleton, lying face down on a large coil of anchor rope. A small barrel, perhaps at one time containing water or wine, was by his side. Perhaps he had fallen from a bunk or hammock in this area where sailors apparently went for rest. Perhaps he had died of thirst like several other sailors on board. The Texas Historical Commission's excavation was completed in 1997. Since then, more than one million artifacts have been cleaned, analyzed, and conserved. At the Conservation Research Laboratory at Texas A&M University, researchers conducted yet another "excavation," chipping away rust and heavy concretions from thousands of wooden and metal artifacts from the Belle. The ship's hull has been reassembled in a giant vat filled with water and a stabilizing compound that has replaced the water and hardened the wet wood. It has taken almost nine years, but the reconstructed Belle is almost ready for public viewing in the new Texas State History Museum in Austin. Learn MoreIn the meantime, you can visit www.texasbeyondhistory.net/belle.html to learn more about this lost ship and its sunken treasure. For archeologists and others interested in Texas history, the thousands of well-preserved artifacts and the ship itself represent a far more valuable treasure than gold bars and silver coins. (Those too, have been recovered from a shipwreck on the Texas coast, but that is another story.)

|

|

|

DNA |

|

Most of the people who sailed on La Belle originally came from France, so researchers wondered if our skeletal sailor might be related to families living in France today. Since the skeleton was found lying next to a cup with the name, C. Barange, they hoped to look for members of the Barange family in France and compare their DNA with that of the sailor. |

|

First they had to take a look at the sailor's DNA. We know that DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid) is present in every cell of the human body and can sometimes be used to help identify and match up family members. So scientists took samples of his brain tissue, his right leg bones, his teeth, and one of his ribs to look for his DNA. All the samples contained DNA, but none of it was human! The sailor's DNA had been contaminated by bacteria and sea organisms that had been living on his skeleton for over 300 years! So, unfortunately, scientists have not been able to genetically link our Mr. C. Barange with any modern-day relatives. Maybe new techniques will allow us to get better samples and help solve this puzzle some day in the future! |

|

|

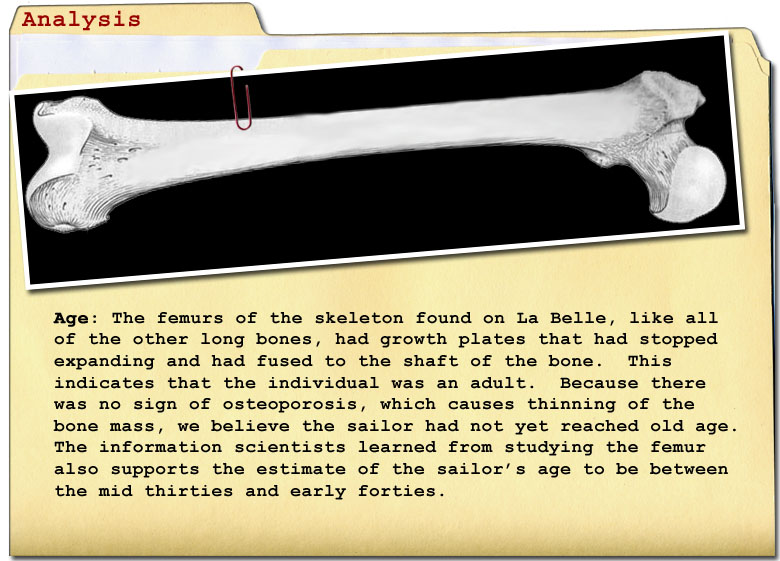

Femur (Thigh bone)

The femur, one of the long bones of the body, is also called the thigh bone. It is the longest, thickest and strongest bone in the human body and can support up to 30 times an adult's weight. The ends of the femur also form part of the hip and part of the knee. When humans are born, they have epiphyseal plates, or growth plates, at the ends of certain bones, such as the femur. Throughout childhood, these plates expand, causing the long bones to grow longer. By the time a person reaches his mid twenties, the plates have stopped growing. In addition, the deterioration of bone caused by diseases such as arthritis and osteoporosis is more often found in older people. By looking at the condition of these areas of the long bones, scientists can determine the approximate age of an individual. The length of the long bones can also be used to help estimate a person's height by comparing the measurements of the bones to other skeletons whose height is already known. |

What can the femur of our sailor tell us? |

|

|

Fibula (Calf bone) and Tibia (Shinbone)

|

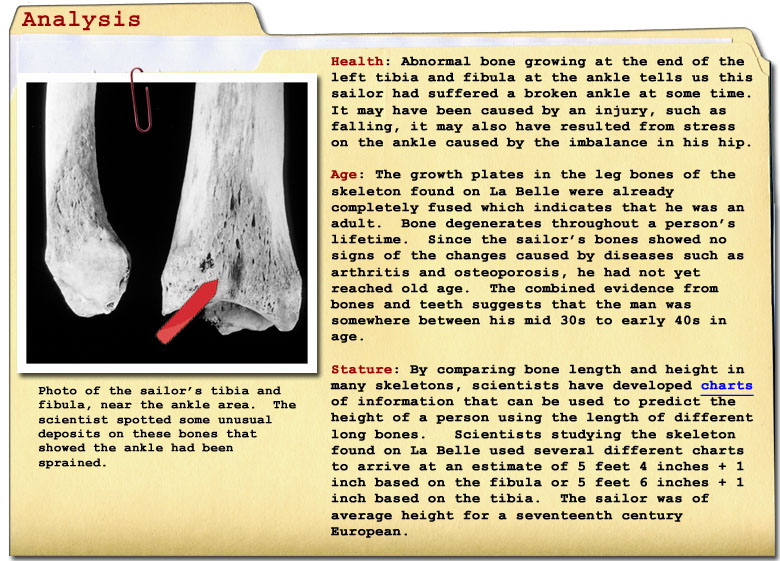

The fibula and tibia are the two bones in the lower leg. The fibula, or calf bone, is the smaller of the two and the most slender of the long bones, the bones of the arms and legs. The tibia, also called the shinbone or shankbone, is the larger and stronger of the two bones. It connects the knee with the ankle bones. When humans are born, they have epiphyseal plates, or growth plates, at the ends of certain bones such as the fibula and tibia. Throughout childhood, these plates expand causing the long bones to grow longer. By the time a person reaches his mid twenties, the plates have stopped growing. In addition, the deterioration of bone caused by diseases such as arthritis and osteoporosis is more often found in older people. By looking at the condition of these areas of the long bones, scientists can determine the approximate age of an individual. The length of the long bones can also be used to help estimate a person's height by comparing the measurements of the bones to other skeletons whose height is already known. |

Compared to humans, we armadillos have short little legs. But we can still scurry around mighty fast and even jump three feet, straight up in the air! |

What can the fibula and tibia of our sailor tell us?

|

|

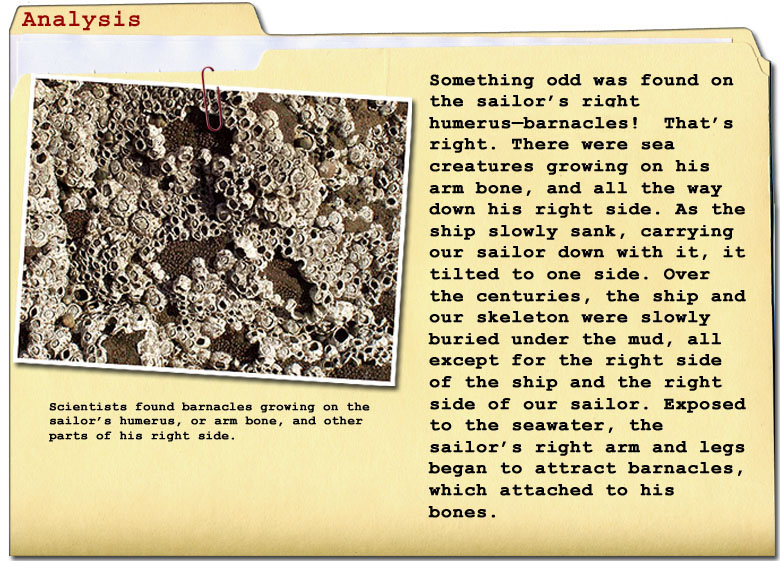

Humerus (Arm bone)

|

The humerus is a long bone in the arm that runs from the shoulder to the elbow. Like the other long bones, it has growth plates that expand as a child matures and fuse to the shaft of the bone once a person reaches adult years. The humerus can also be used to predict height. Various scientists have studied different populations of people to chart the relationship between bone length and height. In the 1890's, a study was made of French males linking the length of arm bones to height. The information from this study helped scientists make a more accurate prediction of the height of the La Belle sailor because it is based on a group of people more like this individual than people living in the 21st century would be. Similar information comes from studies of French soldiers in the 19th century and American prisoners of the War of 1812 being held in England. |

What can the humorous of our sailor tell us? |

|

Age and stature: Other clues from the humerus provided information about the sailor's age and stature (height). The fused growth plates of the humerus from the skeleton support the other evidence that this person was an adult. The length of the humerus from the La Belle skeleton suggests that the sailor stood about 5 feet 4 inches. To 21st century people, that may sound very short for a man, but it was actually the average height for European males two and three centuries ago. The sailor would not have seemed small to his companions aboard the La Belle. |

|

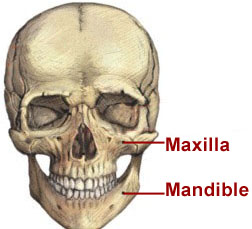

Mandible, Maxilla, and Dentition

(That means Jawbones and Teeth!)

|

The mandible and the maxilla are the lower and upper bones of the jaw. They provide a platform for the teeth and create the shape of the bottom half of a person's face. The two bones are joined together at the sides with hinge joints which allow the mandible to move when we talk or chew. These jawbones and teeth can tell pathologists a lot about a person's age, diet and general health. As we age, humans lose baby teeth, and adult teeth take their place. The number of baby teeth still in the jaw helps identify a skeleton as the remains of either a child, an adolescent or an adult. In addition, the joints of the jaw show signs of wear as a person ages. More wear = greater age! |

|

Seventeenth-century Europeans did not know much about dental care, and the hardships of this sailor's life probably contributed to the poor condition of his teeth. Because he no longer had strong molars for grinding, he had to chew his food with his front teeth, which showed signs of wear. Eating was probably a painful task for him. Growth arrest lines on some of the teeth indicate that the man had lived through at least two times when illness or poor nutrition had slowed the rate of his growth. The upper canines and incisors, teeth used for biting, were bent outwards from the jawbone. Perhaps the sailor had the habit of using his front teeth as tools to grip items such as rope when he worked! |

|

|

|

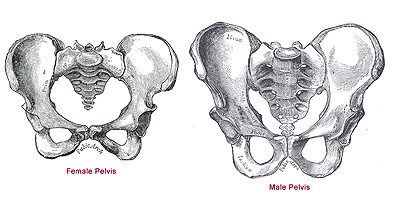

Pelvis and Hips (or Pelvic Girdle)

|

|

|

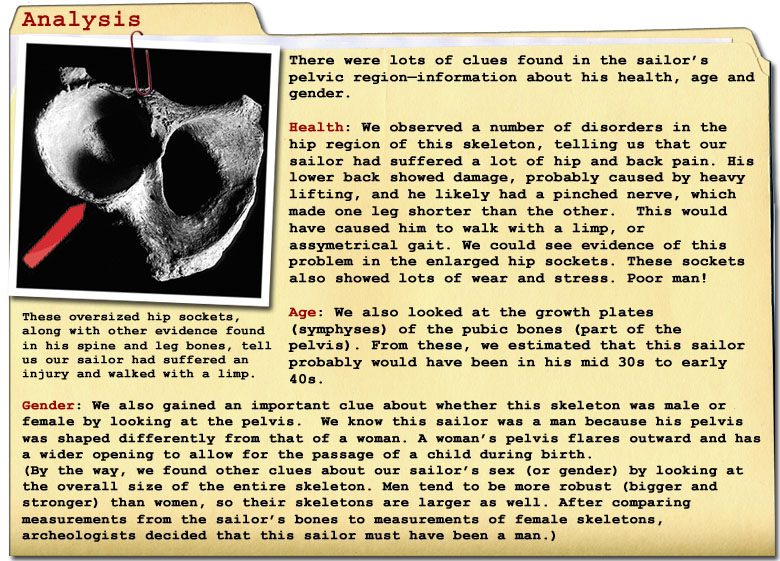

The pelvis is made up of several bones arranged in a basin shape and includes the hip bones. The pelvis plays an important role in the body. It supports the spinal column and protects the abdomen. It also provides a foundation for the leg bones, and acts like a lever to control the body position in relation to the legs (in other words, which way you bend). Finally, the pelvis helps the body bear its weight. The pubic bones, located in the pelvis, gradually change as a person gets older, and these can help us tell how old the person is. |

What can the pelvis of our sailor tell us? |

|

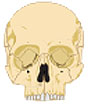

Cranium (The Skull) Cranium (The Skull) |

|

Then, using the CT pictures, technicians created a resin cast, or model, of his skull, onto which a medical illustrator then applied bits of clay, shaping it to match face muscles. Finally, another layer of clay was added to look like the sailor's skin. His body measurements tell us that the sailor was probably a white man, but we have no way of knowing his hair and beard color or length. Many men during this sailor's time did have long hair and beards, so perhaps he did, too. |

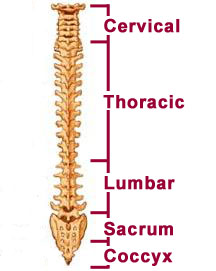

Spinal Column (Vertebral column) or Backbone

|

|

|

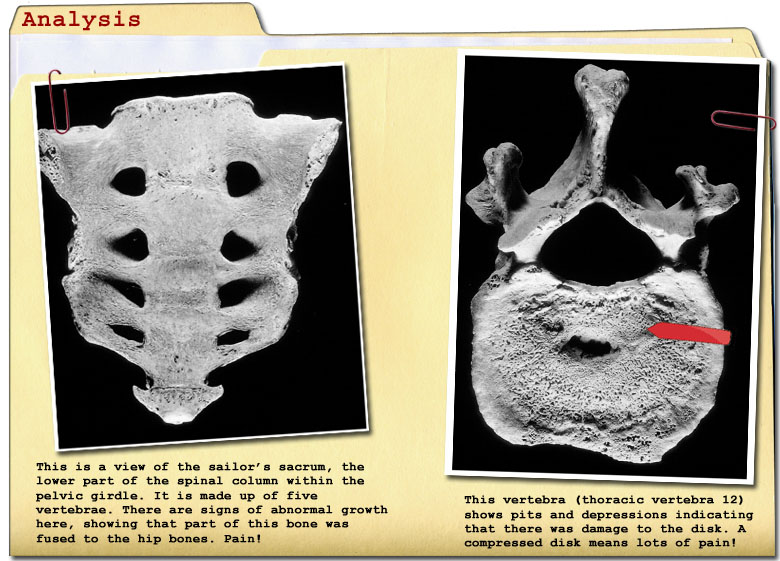

The spinal column, or vertebral column, is made up of small bones "stacked" one on top of the other. There are usually 33 of these small bones, called vertebrae, in humans. Five of them are fused, or joined together, to form the sacrum and four to form the tailbone, two parts of the lower back. The rest of the vertebrae are separated by soft, spongy discs to make a flexible spine that can bend and twist in many directions. Examining the spinal column can help scientists know more about the age and health of an individual. As we age, the discs between the vertebrae can flatten leaving spots where bone grinds against bone. This causes wear marks on the individual bones. In addition, injuries and a variety of diseases can affect the condition of the spine. |

What can the spinal column of our sailor tell us? |

|

Health: The spinal column of the skeleton found on La Belle showed signs of wear, probably the result of years of lifting heavy objects while performing his job as a sailor. In addition, the surfaces of several of the individual vertebrae were marked with pits and depressions. This kind of damage occurs when the soft discs between the vertebrae collapse. The spaces where nerves branch off from the spinal cord to go to other parts of the body become smaller, resulting in a pinched nerve. Unusual bone growth in his lower spine had caused one of the vertebra to fuse to the hip bone, causing the man to stand with his hips tilted instead of straight. This sailor probably limped or favored one leg when he walked and suffered constant pain in his back. |

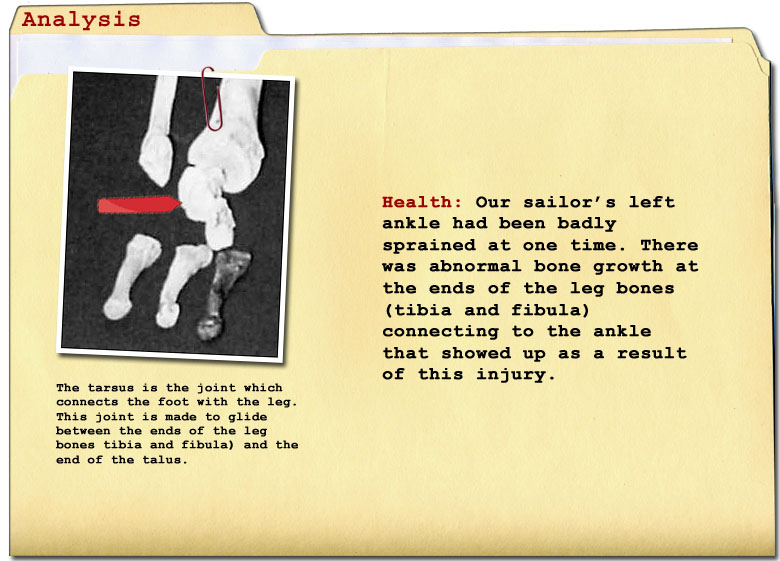

Tarsus (Ankle)

|

|

What can the tarsus of our sailor tell us? |

|

|